Complementary versus Overlapping Distribution Overlapping distribution and contrast

المؤلف:

Mehmet Yavas̡

المؤلف:

Mehmet Yavas̡

المصدر:

Applied English Phonology

المصدر:

Applied English Phonology

الجزء والصفحة:

P31-C2

الجزء والصفحة:

P31-C2

2025-02-26

2025-02-26

1202

1202

Complementary versus Overlapping Distribution

Overlapping distribution and contrast

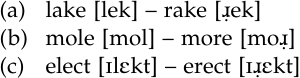

In languages, sounds are in either of two types of distribution. When two sounds are capable of occurring in the same environment, we say that these sounds are in overlapping distribution. For example, the sounds [l] and [ɹ̣] are in overlapping distribution in English, because they can be found in the same environment, as exemplified by the following pairs of words:

The examples above show that the sounds [l] and [ɹ̣] are capable of occurring in the same environment (in word-initial position, followed by the same sound, in (a); in word-final position, preceded by the same sounds, in (b); and medially, preceded and followed by the same sounds, in (c)). It should be mentioned that the environments relevant to the distribution can be defined in terms of word or syllable position, neighboring sounds (preceding and/or following), or suprasegmentals.

When we have an overlapping distribution as shown above, we say that the sounds in question are in a non-predictable distribution. An overlapping distribution is not required to manifest itself in multiple positions; one environment will be enough to conclude the overlap. For example, the sounds [n] and [ŋ] in English may be found in an overlapping distribution only in a syllable-final position (e.g. kin [kɪn] – king [kɪŋ]). This is because [ŋ] can be found in English only in this environment.

When two sounds are found in an overlapping distribution, and the substitution of one sound for the other changes the meaning of the word (e.g. [lek] vs. [ɹ̣ek], [kɪn] vs. [kɪŋ]), we say that they are in contrast, and they are the manifestations of different phonemes.

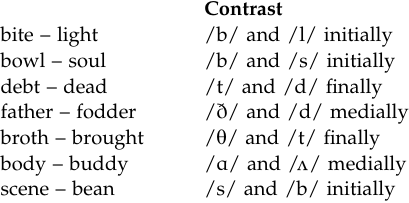

The pairs of words used above to show the overlapping environments and contrasts are known as minimal pairs. Simply defined, minimal pairs are pairs of words that have exactly the same sounds in the same order except for a single difference in sounds, and have different meanings. These are well exemplified in the pairs (a)–(c) above. Notice that the only way we can create a minimal pair with reference to the two sounds involved is to put them in exactly the same environment in terms of word position and the surrounding context. To clarify further, the pair: jail– Yale shows the contrast between /ʤ/ and /j/ in initial position, budge– buzz focuses on the contrast between /ʤ/ and /z/ in final position, while witch– wish contrasts /ʧ/ and /ʃ/ in final position. It should be noted that minimal pairs include forms that have different spellings, as evidenced in jail– Yale. In the following, we provide more examples with different spellings:

While finding minimal pairs is very comforting and makes our job easy in concluding that the ‘suspicious’ pair/group of sounds (i.e. the one we are examining) are in contrast and should belong to separate phonemes, this may not always be possible. The language simply may accidentally lack the needed vocabulary items. This is probably more common in languages with long words and large inventories. However, no language is immune to this. When we do not have the minimal pairs to prove that two or more sounds are in contrast, we look for the ‘near-minimal pair’. This is a pair of words that would be a minimal pair except for some irrelevant difference. What this rather vague definition says is that the potentially influential elements in the linguistic environment are kept constant, while others that are unlikely to influence a change may be different. Essentially, we look at the immediately preceding and immediately following environments, because these are the primary sources of contextual conditioning for changes. For example, if we cannot find an exact minimal pair to show the contrast between [ʃ] and [Ʒ] in English, we can use the words vision [vɪʒən] and mission [mɪʃən], or illusion [əluʒən] and solution [səluʃən]. Although these pairs do not constitute minimal pairs (because the difference is not solely in the suspicious pair of sounds, [ʃ] and [Ʒ], but also related to others), the relevant ‘preceding’ and ‘following’ environments of the suspicious pairs of sounds are kept identical. Similarly, pairs such as lethargy [lεθɚdʒi] and leather [lεðɚ] for [θ] and [ð], and lesion [liʒən] and heathen [hiðən] for [Ʒ] and [ð], would serve as near-minimal pairs. Thus, we can answer the question “Do the two sounds occur in the same/similar environment?” affirmatively, and conclude that the pairs of sounds considered above are in contrast and belong to two separate phonemes.

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة