Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Complementary distribution

المؤلف:

Mehmet Yavas̡

المصدر:

Applied English Phonology

الجزء والصفحة:

P33-C2

2025-02-26

1091

Complementary distribution

The other distributional possibility, complementary distribution, presents the diametrically opposing picture. Here we never find the two or more sounds in the same environment. Stating it simply, we can say that two sounds are in complementary distribution if /χ/ never appears in any of the phonetic environments in which /Y/ occurs. Having said that, we can now go back to some of the examples we gave and re-examine them. The first one concerns the dental and alveolar nasal sounds [n̪] and [n]. In English the distribution of these two sounds is such that they never appear in the same environment (that is, they are mutually exclusive). We find the dental only before /θ/ or /ð/, as in tenth [tεn̪θ], in the game [In̪ ðə. . .], where the other one never appears. When we find the sound /χ/ only in a certain environment, and the sound /Y/ in a completely different environment, then it is impossible for the difference between these two sounds to be contrastive, because a contrast requires an overlapping distribution. In such cases of complementary distribution, we say that these sounds are allophones of one and the same phoneme. We should be reminded, in passing, that the very same two sounds are capable of occurring in the same environment, as we saw in the case of Malayalam, and function contrastively (thus, belong to two separate phonemes) in that language.

Another example of the complementary distribution of an allophonic relationship can be given for [d̪] and [ð] of Spanish. These two sounds can never occur in the same environment in Spanish; [ð] occurs between two vowels or after a nasal, [d̪] occurs in the remaining environments. This is clearly an example of a complementary distribution where the occurrences of the two members are mutually exclusive. Consequently, we say that in Spanish [d̪] and [ð] are the allophones (positional variants) of the same phoneme.

The best analogy (and, surely, a student favorite) for complementary distribution I have heard to date has been provided by the relationship between ‘Superman’ and ‘Clark Kent’ (I don’t know who the credit is due to). Although these two characters belong to the same person, their presence is entirely mutually exclusive (they can never appear in the same environment). While we invariably see ‘Superman’ during the moment of danger, ‘Clark Kent’ is the fellow we encounter in the newspaper office. Thus, these two characters provide an excellent case of complementary distribution.

While it is true to say that the allophones of the same phoneme are in complementary distribution, this assertion can only be unidirectional. That is, we cannot reverse the statement and say “if two sounds are in complementary distribution, then they are the allophones of the same phoneme”. The reason for this may be some defective distribution of certain sounds. The distributions of English [h] and [ŋ] are a case in point. While [ŋ] occurs only as a coda (syllable-final), and never as an onset (syllable-initial), [h] is found only as an onset and never as a coda. The distribution displayed here is a perfect match for the ‘Superman’ and ‘Clark Kent’ situation. Because the contexts are mutually exclusive, the distribution will undoubtedly be labeled as ‘complementary’. Despite this fact, no one has ever suggested (or will ever suggest) that these two sounds should be treated as the allophones of the same phoneme. This is because they do not satisfy the other important requirement of an allophonic relationship, ‘phonetic similarity’. Allophones of the same phoneme always share phonetic features, and thus are phonetically similar. If we look at the two sounds in question, we hardly see any phonetic similarity; [h] is a voiceless glottal fricative, and [ŋ] is a voiced velar nasal. In other words, these sounds do not share anything with respect to place or manner of articulation; nor do they share voicing. Thus, we can state the following generalization: two or more sounds are allophones (positional variants) of the same phoneme, if (a) they are in complementary distribution, and (b) they are phonetically similar.

While examining the environment that might be of relevance, there is one very important aspect to keep in mind, and this is the particular phonetic feature(s) that separate(s) the sounds in the suspicious pair/group. The reason for this is that different changes can and will be stimulated by different environments. For example, if we find one member, e.g. [b], of the suspicious pair in an exclusively intervocalic environment, and never find the other member, e.g. [p], in the same environment, we seem to have a very good case for concluding that these two sounds should be the allophones of the same phoneme. Besides satisfying the requirement of complementary distribution and phonetic closeness between the two sounds, the appearance of the voiced member in an intervocalic environment (surrounding two voiced sounds) is an excellent way to stimulate voicing. In other words, the context makes perfect phonetic sense for the change.

There is no magic formula for arriving at an airtight conclusion for phonetic similarity. However, the following can provide some useful guidelines as to what constitutes a suspicious pair (or group) of sounds that might prove to be the allophones of the same phoneme:

Obstruents

• Voiced–voiceless pairs with same place and manner of articulation (e.g. [p–b], [s–z], [ʧ – ʤ]).

• Pairs of sounds with same voicing and manner of articulation, and rather close places of articulation (e.g. [s– ʃ], [f– θ]).

• Pairs of sounds with same voicing and place of articulation but different manner of articulation (e.g. [t– ʧ], [k–x], [p–ɸ])

Sonorant consonants

• All nasals (especially the ones that are close in place of articulation).

• All liquids (within laterals, within non-laterals, and across these two subgroups).

• Glides [j] and [w] and high vowels [i] and [u] respectively. Glides may also have a relationship with the fricatives of the same or similar places of articulation.

The common theme in all the examples above is that there are more phonetic features that unite them than features that divide them. For example, [s] is a voiceless, alveolar fricative, and [ʃ] is a voiceless, palato-alveolar fricative. In other words, both sounds are voiceless and fricatives. The only feature in which they differ is the place of articulation.

Having reviewed the relevant concepts regarding contrastive and complementary distribution, we can now go back and re-examine the phonetic differences that were easily perceived or overlooked by speakers of certain languages. For example, the difference between the dental and alveolar nasals, [n̪] and [n], is overlooked by speakers of English, but noticed immediately by speakers of Malayalam. In the case of [d] and [ð], the situation was different for speakers of English: while the difference is easily perceived by speakers of English, the same phonetic distinction is overlooked by speakers of Spanish. The reasons for different reactions to the same phonetic differences lie in the way these differences are employed in different languages. While [n–n̪] are in complementary distribution in English and the difference is allophonic, the same sounds are in contrastive distribution and belong to separate phonemes in Malayalam. In English [d– ð] is contrastive, but it is allophonic in Spanish. There seems to be little doubt that contrastiveness plays a major role in the perception of language users. When two sounds are allophones of the same phoneme, a speaker of the language will feel that they are the same sound.

To sum up what has been reviewed so far, we can state that two or more phonetically similar sounds may have a different phonemic (functional) status in different languages. Their status is determined solely by their distribution in a given sound system. If they are in overlapping distribution (that is, can occur in the same environment, which can be verified via existence of a minimal or near-minimal pair), and the substitution of one for the other results in a change of meaning, then these two or more sounds are in contrast and are phonetic manifestations of different phonemes (for example, day [de] and they [ðe] reveal that [d] and [ð] belong to separate phonemes, /d/ and /ð/ respectively). When two sounds are in contrast (i.e. when the difference is phonemic), the speakers of that language develop a high-grade sensitivity toward that difference, and notice any failure to observe it.

If, on the other hand, the distribution of two or more phonetically similar sounds is complementary (that is, they are found in mutually exclusive environments), they are said to be the allophones of one and the same phoneme. The difference between the two or more sounds, then, is allophonic and not phonemic (e.g. [n], [n̥], [n̪], [ɱ] in name, snail, panther, and invite, respectively). In such cases, speakers’ sensitivity to these phonetic differences is extremely low-grade, if it exists at all. The reason for this is that these differences are never utilized to make any meaning differences among words (cf. the difference between [n] and [n̪] in Malayalam cited earlier).

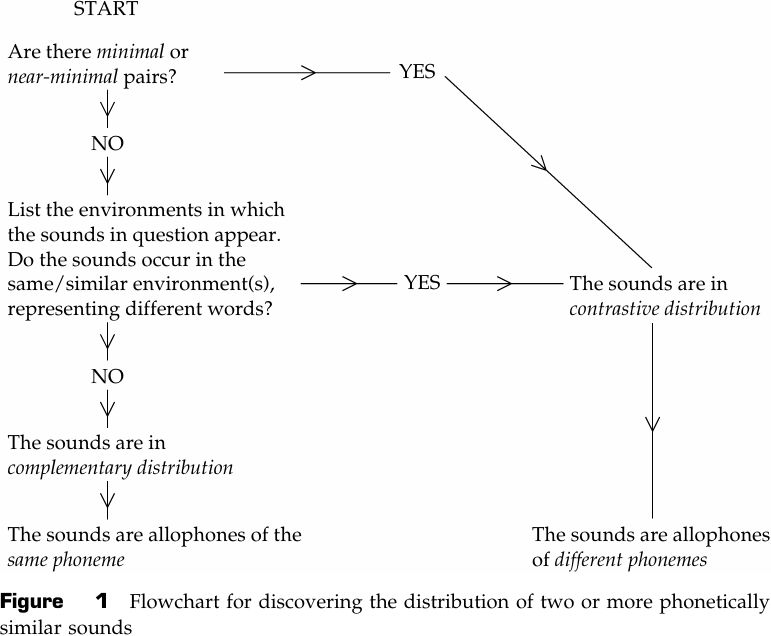

Before we illustrate the points discussed with a mini-demo, it is useful to summarize the strategy we use to decide on the phonemic status of similar sounds (see figure 1).

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)