النبات

النبات

الحيوان

الحيوان

الأحياء المجهرية

الأحياء المجهرية

علم الأمراض

علم الأمراض

التقانة الإحيائية

التقانة الإحيائية

التقنية الحيوية المكروبية

التقنية الحيوية المكروبية

التقنية الحياتية النانوية

التقنية الحياتية النانوية

علم الأجنة

علم الأجنة

الأحياء الجزيئي

الأحياء الجزيئي

علم وظائف الأعضاء

علم وظائف الأعضاء

الغدد

الغدد

المضادات الحيوية

المضادات الحيوية|

Read More

Date: 19-4-2016

Date: 18-4-2016

Date: 18-4-2016

|

Antibody production

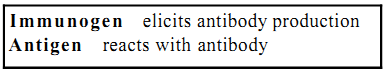

The immune system is designed to ward off “foreign” invaders. Injection of a foreign molecule, usually a protein, into an animal elicits an immune response, which includes the production of antibodies which react with the foreign protein and target it for removal from the system. The foreign protein in this context used to be called an antigen, from antibody generator, but the terminology has changed and now the molecule which elicits antibody production is called an immunogen and the molecule with which the antibody reacts is called an antigen (Fig. 1).

The terminology changed when it was realized that although the immunogen and the antigen are often the same molecule, sometimes they are not. Also, some molecules are antigenic (i.e. they react with antibodies) but are not immunogenic (i.e. they will not elicit antibody production when injected into an animal). The current hypothesis takes account of the fact that the immunogen and the antigen may or may not be the same molecule.

Figure 1. The relationship between immunogens, antibodies and antigen.

Many small molecules will not by themselves elicit antibody production but when conjugated to a larger molecule they will elicit antibodies, which will react with the unconjugated small molecule. Such small molecules are known as haptens. The cut-off in size is not absolute and experience with peptide antibodies (antibodies elicited by peptide immunogens) suggests that it may be that smaller molecules simply take longer to elicit antibodies. For example, free peptides are often able to elicit antibodies, but the antibody titre takes longer to rise than when a peptide conjugated to a carrier protein is used as the immunogen.

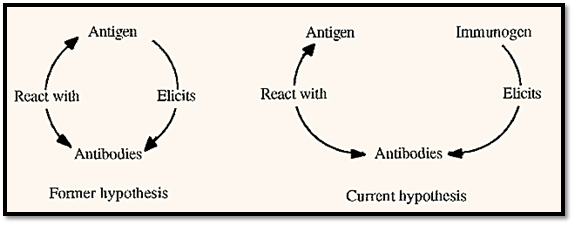

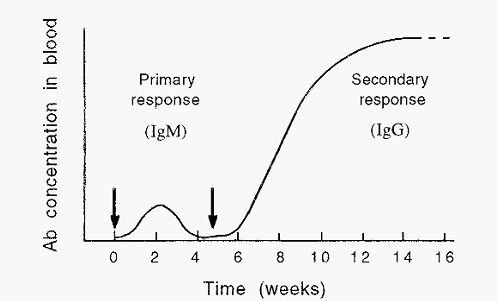

A single injection of an immunogen is not optimally effective in eliciting antibody production. In a natural infection, molecules from the infecting agent will leak from the site of infection to become exposed to the immune system in small amounts, but over an extended time. To elicit antibodies, this natural process must be mimicked. One way would be to inject a small amount of immunogen at a time and to repeat the injection many times over a time period. This for exposure to the immune system in small would work, but it would subject the animal to unnecessary trauma, which is ethically unacceptable. Another way would be to make an emulsion of the aqueous antibody solution with an adjuvant oil and inject this subcutaneously or intramuscularly. The emulsion is made by a process known as trituration. The injected emulsion would exist at a focal site, mimicking a natural infection, and would break down slowly over time, thereby slowly releasing the immunogen and exposing it to the immune system over a period. This is the principle of Freund’s incomplete adjuvant. However, the immune system is particularly geared to combating microbial infection and its response is stimulated by the presence of components of the bacterial cell wall. Freunds complete adjuvant thus contains bacterial cell wall components, in addition to an emulsifying oil. The first injection of an immunogen gives a relatively small response and the antibodies produced are of the high molecular weight IgM type (IgM antibodies are comprised of five subunits, each equivalent to a single IgG molecule, joined together). This is known as the primary response. Further inoculations with the same immunogen gives a much greater secondary response, in which mainly IgG-type antibodies are produced (Fig. 2).

Antibodies arc made by a class of white blood cells (leukocytes) known as B-cells. In any one animal there are a large number of different B-cells, each capable of making a single type of antibody molecule. Each B-cell carries an “advertisement” γ-globulin on its surface and interaction of this molecule with an antigen molecule causes that B-cell to divide into a clone of similar B-cells, a process known as clonal expansion. Some of these B-cells mature into antibody-producing plasma cells and some remain as memory cells. The existence of an expanded clone of memory cells accounts for the faster and more extensive secondary response.

Figure 2. Time-course of the immune response. Arrows indicate inoculations with immunogen.

Making an antiserum

An antiserum, or an antibody isolated from it, constitutes a useful reagent in protein biochemistry. However, it is a reagent which is specific to the immunogen/antigen couple and often it must be prepared in-house, especially when a novel protein is under investigation Preparation of an antiserum starts with the immunogen, which is usually a protein isolated by one or more of the methods described in the previous chapters. The more pure the immunogen, the more specific will be the antibodies which it elicits. For most purposes, therefore, it is best to use as pure an immunogen as possible.

Alternatively, for the production of so-called peptide antibodies, the immunogen might be a synthetic peptide of ten or more residues. The peptide is chosen from the amino acid sequence of the Ag of interest, i.e. the complete protein which it is hoped the Abs will recognize. For peptide antibodies to recognize the whole protein, it is necessary that the peptide sequence chosen be accessible, i.e. it must be on the surface of the protein. This can be readily determined if the 3-D structure of the protein is known. If the 3-D structure is not known, then the peptide can be chosen by analysis of the amino acid sequence of the Ag of interest for hydrophobicity (since hydrophilic residues will tend to be on the surface) or mobility (since residues on the surface, and especially at the N- or C-terminus are likely to be more mobile).

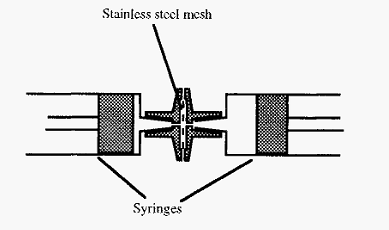

For inoculation into an animal, the immunogen must be emulsified with Freunds complete adjuvant and this can conveniently be done by trituration in an apparatus such as shown in Fig. 3. In this device, the solutions are emulsified by passage back and forth between two syringes, through a fine stainless steel mesh.

Figure 3. A device for emulsifying antibody solution with adjuvant oil.

The triturated immunogen/adjuvant emulsion may be injected subcutaneously in a rabbit, or into the breast muscle of a laying hen. Animals have an idiosyncratic response to immunogens and so it is best to use at least two animals, in case the one is a poor responder this is provided sufficient immunogen is available, of course. A typical inoculation schedule would involve injection of 50-----100 µg of protein per time, first in Freund’s complete adjuvant, followed at one, two, four and six weeks thereafter by further inoculations in Freunds incomplete adjuvant. If necessary, further booster inoculations can be given at monthly intervals. In the case of rabbits, blood samples are taken immediately before each inoculation, so that the increase in antibody titre with time can be followed. An illustrative example of the increase in antibody titre with time is shown in Fig. 4.

Figure 4. A typical ELISA of the progress of an immunization. The open triangles represent preimmune serum and the other three symbols represent serum at 2,4 and 6 weeks.

An advantage of using hens for antibody production is that it is not necessary to bleed them in order to harvest the antibodies. It is, of course, necessary to bleed rabbits and this may be done by warming one of their ears with a hot, wet towel, in order to dilate the blood vessels, and nicking the peripheral ear vein with a sharp scalpel blade. About 25 ml can be collected from a rabbit at one time. The blood is best collected into a clean, dry 25 ml conical flask as this has an almost optimal ratio of volume to surface area and the exposed area is also minimal. With a high volume to surface area ratio, the clot can more easily contract away from the vessel walls, thereby obviating tearing of the clot and lysis of the red blood cells. Optimal clot formation is promoted by incubation overnight at 4C. Ideally, no haemolysis should occur and the serum should be a pale straw colour. It may be harvested by careful aspiration with a Pasteur pipette.

An IgG preparation may be isolated from the antiserum, or IgY isolated from egg yolks, by precipitation with polyethylene glyco .

References

Dennison, C. (2002). A guide to protein isolation . School of Molecular mid Cellular Biosciences, University of Natal . Kluwer Academic Publishers new york, Boston, Dordrecht, London, Moscow .

|

|

|

|

"إنقاص الوزن".. مشروب تقليدي قد يتفوق على حقن "أوزيمبيك"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

الصين تحقق اختراقا بطائرة مسيرة مزودة بالذكاء الاصطناعي

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

قسم شؤون المعارف ووفد من جامعة البصرة يبحثان سبل تعزيز التعاون المشترك

|

|

|