Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2024-03-28

Date: 2024-04-17

Date: 2024-03-09

|

What has been written about the social history of the language again comprises quite a few varying accounts, with certain key factors such as the early presence of a West-Indian English speaker or the impact of the Melanesian Mission generally not being discussed. The story of the mutiny on the Bounty has been popularized by numerous novels, plays and films, and Pitcairn Island, where the Bounty mutineers settled in 1792, has come to stand as a metaphor for a South Sea Utopia. When nine British sailors, twelve Tahitian and Tubudian women and six Tahitian men arrived on Pitcairn, the island was uninhabited.

By 1800, following a period of violence, John Adams was the sole survivor with 10 women and 23 children. When he died in 1829 the island had become a model Christian community of about 80. Because of food and water shortages, Pitcairn Islanders were removed to Tahiti in 1821, but returned to the island in the same year. In 1839 the population had grown to 100, by 1850 it had reached 156. As fishstocks became scarce and the island degraded, in 1853 the inhabitants solicited the aid of the British Government to transfer them to another island which had become uninhabited, Norfolk. In 1856 all 194 Pitcairn Islanders settled on Norfolk, but a number of families returned to Pitcairn shortly afterwards.

Norfolk Island was discovered by Captain Cook in 1779 and because of its ample natural resources and isolated position was made a British Penal Colony in 1877. The first penal settlement was abandoned in 1814, but a second penal settlement was built in 1825 at a location for the “extremist punishment short of death” (Hoare 1982: 35) and “a cesspool of sodomy, massacre and exploitation” (Christian 1982: 12).

Following much criticism, the settlement was closed down in 1854. The third settlement is that by the Pitcairners who arrived in 1856 and were given title to about 1/4 of the total land area rather than the entire island as they had been led to believe. One reason for this is that the Melanesian mission, operating from Auckland, also had designs on Norfolk, and they were granted about 400 hectares of land in 1867. A boarding school catering for about two hundred students from different parts of Melanesia was set up and remained in operation until 1920.

Both islands thus provide laboratory conditions to study linguistic processes such as language contact, dialect mixing, and languages in competition. Different linguists have tended to concentrate on only one of these, as key factor, ignoring that all of them were important at some point in the history of Pitkern and Norfuk, plus other factors such as deliberate creation of language.

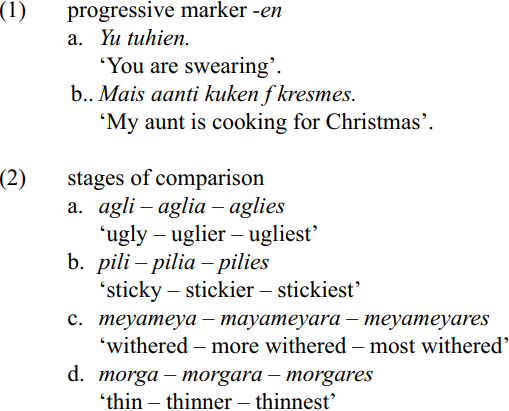

Ross and Moverley (1964) characterize what they called Pitcairnese as the outcome of language mixing, and provide numerous details about Tahitian lexicon and grammar, as well as details on dialect features. They provide details on the provenance and likely dialect affiliation of the mutineers (1964: 49, 137). As most men were killed in the first years of settlement, only the following are likely to have influenced the emerging language: Matthew Quintal (Cornishman), William McKoy (Scotsman), Edward Young (St. Kitts, West Indies), and John Adams (Cockney). The two principal linguistic socializers for the first generation of children born on Pitcairn were Young and Adams. Young contributed a number of St. Kitts pronunciations and lexemes, [l] for [r] in words such as stole ‘story’, klai ‘cry’, and morga ‘thin’. John Adams created the social conditions in which standard acrolectal English against all demographic odds could prevail as the dominant language of the community.

There is ample evidence that the Tahitians were not regarded as full human beings by the white members of the community and that racism was strong. This is reflected, for instance, in the absence of place-names remembering the non-European settlers. To date, no Tahitian woman is thus remembered by a place-name on either Pitcairn or Norfolk Island, though there now is a revaluation and appreciation of the Tahitian contribution and the word formaadha ‘foremother’ is being used in modern Norfuk.

Tahitian dress, language and eventually diet were gradually suppressed and given up, and policies put in place that were based on British and American models. Of particular importance has been the education system, which has tended to be in the hands of outsiders (Englishmen, American Seventh Day Adventist missionaries, and finally New Zealanders on Pitcairn Island; first British and then Australian teachers on Norfolk). Evidence from language use and attitudes in the Norfolk Education System suggests that from about 1900, language became a major issue and generations of teachers were actively involved in marginalizing, suppressing and ridiculing the Norfuk Language. Children who spoke it were punished, and a sense of shame remains when older islanders speak the language in front of outsiders. More positive attitudes towards Norfuk date from the late 1980s, and in the late 1990s Norfuk language was formally introduced into the school as part of Norfolk Studies. There are now plans to teach Norfuk Language from Preschool to Year 10.

The ambivalent attitudes towards Norfuk are reflected in two areas of language mixing. First, it is remarkable that words of Tahitian origin tend to be predominant in marked domains of language: taboo words, negative characterizations, undesirable and unnatural phenomena and properties. Examples include: eeyulla ‘adolescent, immature, or not dry behind the ears’; gari ‘accumulation of dirt, dust, grime, grease, etc.’; hoopaye ‘mucous secreted in the nose’; howa-howa ‘to soil one’s pants from a bowel movement, have diarrhoea’; hullo (1) ‘a person of no consequence’, (2) ‘having nothing of any value; dirt poor’; iti ‘any of the wasting diseases but mainly referring to tuberculosis’; iwi ‘stunted, undersized’; laha (also lu-hu) ‘dandruff’; loosah ‘menses, menstruation’; maioe ‘given to whimpering or crying a lot, like a child, but not necessarily a child’; nanu ‘jealous’; pontoo ‘unkempt, scruffy’; po-o ‘barren or unfertile soil’; tarpou ‘stains on the hands caused from peeling some fruits and vegetables’; tinai (1) ‘to gaze at with envy’, (2) ‘an avaricious person’; toohi ‘to curse, blaspheme, or swear’; uuaa ‘sitting ungraciously’; uma-oola ‘awkward, ungainly, clumsy’.

Some of these words may have originated in the nursery context rather than being indices of negative racial attitudes, but the overwhelming impression is that Tahitian words are the semantically marked forms: 98% of the forms in the 100- word standard Swadesh list are of English origin (the exception being aklan ‘we’ and the form lieg which stands for ‘foot’ and ‘leg’) and only about 5% of all words come from sources other than English (Tahitian, St. Kitts, Melanesian Pidgin English)

A second remarkable property is that words of English, Tahitian and other languages do not differ, as they do in most contact languages, in their susceptibility to morphosyntactic rules, suggesting a full integration of the two languages.

The single most important question regarding Pitkern/Norfuk remains its linguistic nature. In spite of considerable interest from dialectologists, creolists and researchers into language contact phenomena, most conclusions have been presented on the basis of very sketchy evidence and second-hand information, and the task to provide an observationally adequate account of the development and present-day use of Pitkern/Norfuk is far from completed. A particular obstacle has been the assumption that one is dealing with a single monolithic phenomenon, whereas in fact there is strong evidence for historical discontinuities, extensive idiolectal variation and a wide range of proficiencies.

For instance, the very few samples of Pitkern from the 1820s bear relatively little similarity to present-day varieties. Captain Raine (1824: 37) recorded the following observations about the low level of literacy and simplicity of lifestyle:

In their conversation they were always anxious for information on the Scriptures, and expressed their sorrow that they did not understand all they read. One of them in talking with the Doctor showed such a knowledge of the Scriptures as is worthy of remark, particularly as it evinced their simplicity and harmlessness; the subject was a quarrelling, on which he said, ‘Suppose one man strike me, I no strike again, for it says, suppose one strike you on one side, turn the other to him; suppose he bad man strike me I no strike him, because no good that; suppose he kill me, he can’t kill the soul – he no can grasp that, that go to God, much better place than here.’ At another time, pointing to all the scene around him, and to the Heavens, he said, ‘God make all these, sun, moon, and stars and’ he added, with surprise, ‘the book say some people live who not know who made these!’ This appeared to him a great sin. They all of them frequently said, ‘if they no pray to God they grow wicked, and then God have nothing to do with the wicked, you know’.

Differences with present-day varieties in the areas of word order, use of relativizers and tags are evident. In common with present-day Norfuk are negation, conditional clauses and code mixing.

There probably never was a totally homogeneous speech community in the sense that every member believed they were speaking a language other than English, or in the sense of sharing the same linguistic role models, and there are still differences in lexical choice and pronunciation among different families. The language emerged in the tension between Tahitians and British, Islanders and Outsiders, Royalists and Independence Supporters. Some of the unique factors in the history of the language include:

(a) Pitcairn Island was the first English-speaking territory with compulsory literacy (from the 1820s). John Adams, towards the end of his life, invited English teachers to the island who not only ran the education system, but played a full part in many aspects of community life and were role models for community members. Proficiency in British Standard English has been held in high regard since their arrival. For speakers under the age of 30, Australian English has become the most widely accepted model.

(b) Literacy, for a significant part of its history, was strongly associated with religion, the Bible and religious texts being the predominant reading materials, and Biblical language an important model. Children were exposed to Biblical English from early childhood and it seems unlikely that any child was allowed to grow up without a thorough knowledge of this variety. Literate forms of Tahitian were not employed by the Pitcairners, and Pitkern/Norfuk was never used for religious writings or discourses.

(c) Pitkern/Norfuk is not a language in which all its speakers’ needs can be expressed. It has a very limited vocabulary, about 1500 words (Eira, Magdalena and Mühlhäusler 2002), and it has not been used for public and high functions until very recently. However, since about 1990 the visibility of Norfuk has increased significantly. It features on the signage of the National Parks, the airport and departure forms, the names of businesses e.g. Nuffka Apartments ‘Kingfisher or Norfolker’, Wetls Daun A’Taun ‘victuals down in Kingston Town’ and house names Dii el duu ‘able to do, make do’, Mais hoem and in local songs.

(d) The extent to which Pitkern/Norfuk was socially institutionalized appears to vary with political circumstances and the desire of the population to express a separate identity. Greater use of Pitkern/Norfuk and concomitant loss of proficiency in English appear to coincide with the wish to distinguish oneself from outsiders. Laycock (1989) suggested that Pitkern/Norfuk came into being as a cant, in 1836, when the entire Pitcairn community was briefly resettled in Tahiti and found themselves at odds with the moral laxness which prevailed there at the time. However, the deliberate distancing from acrolectal English is documented even before the mutiny, when sailors mixed Tahitian expressions with English in order to taunt their unpopular captain.

The wish not to be Australian has been a strong motif in maintaining a separate form of speech on Norfolk Island, and the current conflict between Pitcairn Islanders and Britain (over a matter of police investigation) may trigger off a revival of the Pitcairn variety. Pitkern/Norfuk thus can be studied as an indicator of changing perceptions of identity. The situation on Norfolk Island today is reminiscent of Labov’s observations on Martha’s Vineyard (1972b), where non-standard forms have become reactivated by members of the younger generation opposed to mass tourism from the mainland. The tendency of past researchers to regard the Norfolk Island language from a purely structural perspective must be regarded as problematic, as structural properties cannot easily be separated from sociohistorical forces. If anything, it is the indexical rather than the structural and referential properties of Pitkern/Norfuk that lend this language its special character. As regards deviations from standard English, no single cause or explanation seems sufficient. Unsurprisingly, a number of features from older, eighteenth-century English are retained, though contemporary varieties of British, New Zealand, Australian and American English are influencing the language today.

The fact that the language developed on a remote island has led observers to believe that it developed in isolation. The exact opposite appears to be the case, however. Apart from a brief period before 1810, outside visitors were a very common phenomenon on Pitcairn (Pitcairn Island was one of the main ports of call in the Pacific until the arrival of modern intercontinental air traffic). Outsiders (not descended from the mutineers) form a significant part of both communities. Intermarriage is common, and both communities were actively involved in whaling, mission work and travelled for education and health purposes. Some of the generalizations about Island Creoles (Chaudenson 1998) apply to Pitkern and Norfuk as well.

One of the crucial bits of evidence, informal speech of young children at these dates, is missing. The children that we have observed on Norfolk Island in recent years are dominant speakers of English. Flint and Harrison’s data suggest that there was a change from Norfuk to English being the dominant language of the young generation in the 1950s.

|

|

|

|

للعاملين في الليل.. حيلة صحية تجنبكم خطر هذا النوع من العمل

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

"ناسا" تحتفي برائد الفضاء السوفياتي يوري غاغارين

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

المجمع العلمي يقيم ورشة تطويرية ودورة قرآنية في النجف والديوانية

|

|

|