Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2023-11-03

Date: 2023-11-25

Date: 2023-09-21

|

Thus far, we have argued that the language faculty incorporates a set of universal principles which guide the child in acquiring a grammar. However, it clearly cannot be the case that all aspects of the grammar of languages are universal; if this were so, all natural language grammars would be the same and there would be no grammatical learning involved in language acquisition (i.e. no need for children to learn anything about the grammar of sentences in the language they are acquiring), only lexical learning (viz. learning the lexical items/words in the language and their idiosyncratic linguistic properties, e.g. whether a given item has an irregular plural or past-tense form). But although there are universal principles which determine the broad outlines of the grammar of natural languages, there also seem to be language-particular aspects of grammar which children have to learn as part of the task of acquiring their native language. Thus, language acquisition involves not only lexical learning but also some grammatical learning. Let’s take a closer look at the grammatical learning involved, and what it tells us about the language acquisition process.

Clearly, grammatical learning is not going to involve learning those aspects of grammar which are determined by universal (hence innate) grammatical operations and principles. Rather, grammatical learning will be limited to those parameters (i.e. dimensions or aspects) of grammar which are subject to language particular variation (and hence vary from one language to another). In other words, grammatical learning will be limited to parametrized aspects of grammar (i.e. those aspects of grammar which are subject to parametric variation from one language to another). The obvious way to determine just what aspects of the grammar of their native language children have to learn is to examine the range of parametric variation found in the grammars of different (adult) natural languages.

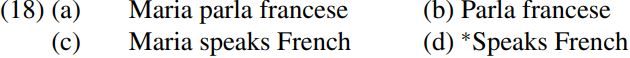

We can illustrate one type of parametric variation across languages in terms of the following contrast between the Italian examples in (18a,b) below, and their English counterparts in (18c,d):

As (18a) and (18c) illustrate, the Italian verb parlare and its English counter-part speak (as used here) are two-place predicates which require both a subject argument like Maria and an object argument like francese/French: in both cases, the verb is finite (more specifically it is a present-tense form) and agrees with its subject Maria (and hence is a third-person-singular form). But what are we to make of Italian sentences like (18b) Parla francese (= ‘Speaks French’) in which the verb parla ‘speaks’ has the overt complement francese ‘French’ but has no overt subject? The answer suggested in work over the past few decades is that the verb in such cases has a null subject which can be thought of as a silent or invisible counterpart of the pronouns he/she which appear in the corresponding English translation ‘He/She speaks French’. This null subject is conventionally designated as pro, so that (18b) has the structure pro parla francese ‘pro speaks French’, where pro is a null-subject pronoun.

There are two reasons for thinking that the verb parla ‘speaks’ has a null subject in (18b). Firstly, parlare ‘speak’ (in the relevant use) is a two-place predicate which requires both a subject argument and an object argument: under the null-subject analysis, its subject argument is pro (a null pronoun). Secondly, finite verbs agree with their subjects in Italian: hence, in order to account for the fact that the verb parla is in the third-person-singular form in (18b), we need to posit that it has a third-person-singular subject; under the null-subject analysis, we can say that parla ‘speaks’ has a null pronoun (pro) as its subject, and that pro (if used to refer to Maria) is a third-person-feminine-singular pronoun.

The more general conclusion to be drawn from our discussion is that in languages like Italian, finite verbs (i.e. verbs which carry present/past etc. tense) can have either an overt subject like Maria or a null pro subject. But things are very different in English. Although a finite verb like speaks can have an overt subject like Maria in English, it cannot normally have a null pro subject – hence the ungrammaticality of (18d) ∗Speaks French. So, finite verbs in a language like Italian can have either overt or null subjects, but in a language like English, finite verbs can generally have only overt subjects, not null subjects. We can describe the differences between the two types of language by saying that Italian is a null-subject language, whereas English is a non-null-subject language. More generally, there appears to be parametric variation between languages as to whether or not they allow finite verbs to have null subjects. The relevant parameter (termed the Null-Subject Parameter) would appear to be a binary one, with only two possible settings for any given language L, viz. L either does or doesn’t allow finite verbs to have null subjects. There appears to be no language which allows the subjects of some finite verbs to be null, but not others – e.g. no language in which it is OK to say Drinks wine (meaning ‘He/she drinks wine’) but not OK to say Eats pasta (meaning ‘He/she eats pasta’). The range of grammatical variation found across languages appears to be strictly limited to just two possibilities – languages either do or don’t systematically allow finite verbs to have null subjects. (A complication glossed over here is posed by languages in which only some finite verb forms can have null subjects: see Vainikka and Levy 1999 and the collection of papers in Jaeggli and Safir 1989 for illustration and discussion.)

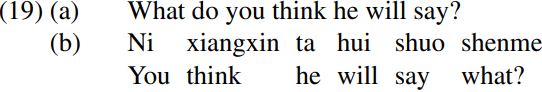

A more familiar aspect of grammar which appears to be parametrized relates to word order, in that different types of language have different word orders in specific types of construction. One type of word-order variation can be illustrated in relation to the following contrast between English and Chinese questions:

In simple wh-questions in English (i.e. questions containing a single word beginning with wh- like what/where/when/why) the wh-expression is moved to the beginning of the sentence, as is the case with what in (19a). By contrast, in Chinese, the wh-word does not move to the front of the sentence, but rather remains in situ (i.e. in the same place as would be occupied by a corresponding non-interrogative expression), so that shenme ‘what’ is positioned after the verb shuo ‘say’ because it is the (direct object) complement of the verb, and complements of the relevant type are normally positioned after their verbs in Chinese. Thus, another parameter of variation between languages is the wh-parameter – a parameter which determines whether wh-expressions can be fronted (i.e. moved to the front of the overall interrogative structure containing them) or not. Significantly, this parameter again appears to be one which is binary in nature, in that it allows for only two possibilities – viz. a language either does or doesn’t allow wh-movement (i.e. movement of wh-expressions to the front of the sentence). Many other possibilities for wh-movement just don’t seem to occur in natural language: for example, there is no language in which the counterpart of who undergoes wh-fronting but not the counterpart of what (e.g. no language in which it is OK to say Who did you see? but not What did you see?). Likewise, there is no language in which wh-complements of some verbs can undergo fronting, but not wh-complements of other verbs (e.g. no language in which it is OK to say What did he drink? but not What did he eat?). It would seem that the range of parametric variation found with respect to wh-fronting is limited to just two possibilities: viz. a language either does or doesn’t allow wh-expressions to be systematically fronted. (However, it should be noted that a number of complications are overlooked here in the interest of simplifying exposition: e.g. some languages like English allow only one wh-expression to be fronted in this way, whereas others allow more than one wh-expression to be fronted; see  2002a for a recent account. An additional complication is posed by the fact that wh-movement appears to be optional in some languages, either in main clauses, or in main and complement clauses alike: see Denham 2000; Cheng and Rooryck 2000.)

2002a for a recent account. An additional complication is posed by the fact that wh-movement appears to be optional in some languages, either in main clauses, or in main and complement clauses alike: see Denham 2000; Cheng and Rooryck 2000.)

Let’s now turn to look at a rather different type of word-order variation, concerning the relative position of heads and complements within phrases. It is a general (indeed, universal) property of phrases that every phrase has a head word which determines the nature of the overall phrase. For example, an expression such as students of philosophy is a plural noun phrase because its head word (i.e. the key word in the phrase whose nature determines the properties of the overall phrase) is the plural noun students: the noun students (and not the noun philosophy) is the head word because the phrase students of philosophy denotes kinds of student, not kinds of philosophy. The following expression of philosophy which combines with the head noun students to form the noun phrase students of philosophy functions as the complement of the noun students. In much the same way, an expression such as in the kitchen is a prepositional phrase which comprises the head preposition in and its complement the kitchen. Likewise, an expression such as stay with me is a verb phrase which comprises the head verb stay and its complement with me. And similarly, an expression such as fond of fast food is an adjectival phrase formed by combining the head adjective fond with its complement of fast food.

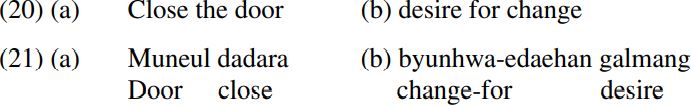

In English all heads (whether nouns, verbs, prepositions, or adjectives etc.) normally precede their complements; however, there are also languages like Korean in which all heads normally follow their complements. In informal terms, we can say that English is a head-first language, whereas Korean is a head-last language. The differences between the two languages can be illustrated by comparing the English examples in (20) below with their Korean counterparts in (21):

In the English verb phrase close the door in (20a), the head verb close precedes its complement the door; if we suppose that the door is a determiner phrase, then the head of the phrase (= the determiner the) precedes its complement (= the noun door). Likewise, in the English noun phrase desire for change in (20b), the head noun desire precedes its complement for change; the complement for change is in turn a prepositional phrase in which the head preposition for likewise precedes its complement change. Since English consistently positions heads before complements, it is a head-first language. By contrast, we find precisely the opposite ordering in Korean. In the verb phrase muneul dadara (literally ‘door close’) in (21a), the head verb dadara ‘close’ follows its complement muneul ‘door’; likewise, in the noun phrase byunhwa-edaehan galmang (literally ‘change-for desire’) in (21b) the head noun galmang ‘desire’ follows its complement byunhwa-edaehan ‘change-for’; the expression byunhwa-edaehan ‘change-for’ is in turn a prepositional phrase whose head preposition edaehan ‘for/about’ follows its complement byunhwa ‘change’ (so that edaehan might more appropriately be called a postposition; prepositions and postpositions are differents kinds of adposition). Since Korean consistently positions heads after their complements, it is a head-last language. Given that English is head-first and Korean head-last, it is clear that the relative positioning of heads with respect to their complements is one word-order parameter along which languages differ; the relevant parameter is termed the Head-Position Parameter.

It should be noted, however, that word-order variation in respect of the relative positioning of heads and complements falls within narrowly circumscribed limits. There are many logically possible types of word-order variation which just don’t seem to occur in natural languages. For example, we might imagine that in a given language some verbs would precede and others follow their complements, so that (e.g.) if two new hypothetical verbs like scrunge and plurg were coined in English, then scrunge might take a following complement, and plurg a preceding complement. And yet, this doesn’t ever seem to happen: rather all verbs typically occupy the same position in a given language with respect to a given type of complement. (A complication overlooked here in the interest of expository simplicity is that some languages position some types of head before their complements, and other types of head after their complements: German is one such language, as you will see from exercise 1.2.)

What this suggests is that there are universal constraints (i.e. restrictions) on the range of parametric variation found across languages in respect of the relative ordering of heads and complements. It would seem as if there are only two different possibilities which the theory of Universal Grammar allows for: a given type of structure in a given language must either be head-first (with the relevant heads positioned before their complements), or head-last (with the relevant heads positioned after their complements). Many other logically possible orderings of heads with respect to complements appear not to be found in natural language grammars. The obvious question to ask is why this should be. The answer given by the theory of parameters is that the language faculty imposes genetic constraints on the range of parametric variation permitted in natural language grammars. In the case of the Head-Position Parameter (i.e. the parameter which determines the relative positioning of heads with respect to their complements), the language faculty allows only a binary set of possibilities – namely that a given kind of structure in a given language is either consistently head-first or consistently head-last.

We can generalize our discussion in the following terms. If the Head-Position Parameter reduces to a simple binary choice, and if the Wh-Parameter and the Null-Subject Parameter also involve binary choices, it seems implausible that binarity could be an accidental property of these particular parameters. Rather, it seems much more likely that it is an inherent property of parameters that they constrain the range of structural variation between languages, and limit it to a simple binary choice. Generalizing still further, it seems possible that all grammatical variation between languages can be characterized in terms of a set of parameters, and that for each parameter, the language faculty specifies a binary choice of possible values for the parameter.

|

|

|

|

التوتر والسرطان.. علماء يحذرون من "صلة خطيرة"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

مرآة السيارة: مدى دقة عكسها للصورة الصحيحة

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

نحو شراكة وطنية متكاملة.. الأمين العام للعتبة الحسينية يبحث مع وكيل وزارة الخارجية آفاق التعاون المؤسسي

|

|

|