Metapragmatics in use

المؤلف:

Jonathan Culpeper and Michael Haugh

المؤلف:

Jonathan Culpeper and Michael Haugh

المصدر:

Pragmatics and the English Language

المصدر:

Pragmatics and the English Language

الجزء والصفحة:

258-8

الجزء والصفحة:

258-8

31-5-2022

31-5-2022

1419

1419

Metapragmatics in use

Metapragmatic awareness lies at the core of a number of important pragmatic phenomena. In many instances, this reflexive awareness is not always accessible or highly salient to participants. It may be inherent to their use of language, but it is not necessarily something they can articulate. There are, however, cases where metapragmatic awareness itself may become highly salient in discourse. The most obvious example of this is the use of metapragmatic commentary to “influence and negotiate how an utterance is or should have been heard, or [to] try to modify the values attributed to it” (Jaworskiń et al. 2004: 4); in other words, the strategic deployment of comments about language use in order to (re)negotiate interpretations of pragmatic meanings, pragmatic acts, and interpersonal relations, attitudes and evaluations. Hübler and Bublitz (2007) term such phenomena “metapragmatics in use”. They list some of the functions of metapragmatic commentary, including:

Given this list is not by any means exhaustive, it is clear that metapragmatic commentary (or, more broadly, acts) can be used to accomplish all sorts of different pragmatic work.

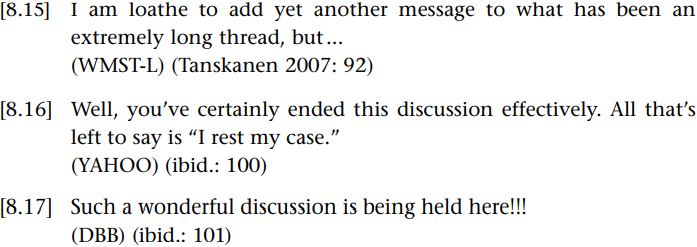

In a study of metapragmatic utterances that arise in computer-mediated interactions in a number of different mailing lists, for instance, Tanskanen (2007) illustrates how participants can use metapragmatic utterances to accomplish assessments of the degree of appropriateness of either their own or others’ posts, or to clarify their own contributions where some misunderstanding is perceived. Such comments were thus found to be designed to (1) accomplish judgements of appropriateness (see example [8.15]), (2) control and plan subsequent interaction (example [8.16]), or (3) give feedback on ongoing interaction (example [8.17]):

Such metapragmatic comments thus illustrate how users display reflexive awareness in making posts to such lists, as through them we can see how they “adopt the perspective of their fellow communicators” in “anticipating potential problems” in such forums (Tanskanen 2007: 88). More generally, we can observe how metapragmatic comments are designed to avoid both misinterpretation and unwanted relational or attitudinal implications, by other participants.

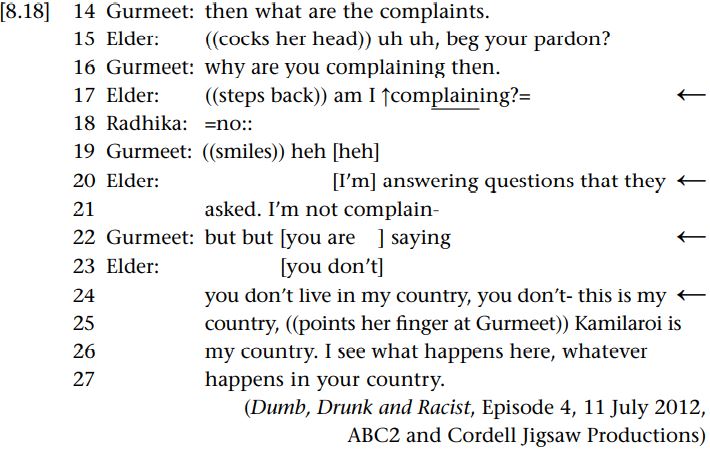

In some cases, however, metapragmatic comments are deployed in order to negotiate or even dispute particular pragmatic meanings, pragmatic acts, interpersonal relations and attitudes, and so on. Consider the following extract from a documentary where four Indians have been touring to get a first-hand understanding of race relations. Preceding this particular excerpt, Gurmeet has suggested to an Aboriginal elder that indigenous Australians should have “specific educational institutions for Aboriginals”, to which the elder responds that such institutions already exist. The excerpt itself begins when Gurmeet subsequently asks why the elder has “complaints” about the past and current situation of indigenous Australians:

While the elder’s initial response in line 15 is indicative not only of possible forthcoming disagreement with what is supposed through Gurmeet’s question (i.e. that the elder has been complaining), but also that there is some issue in regards to the propriety of Gurmeet’s question. Gurmeet nevertheless repeats essentially the same question in line 16. This time the elder’s offence at the terms of the question becomes more evident in her rising pitch, stepping backwards and formulation of a “rhetorical question” in line 17. She then attempts to reformulate her prior turns as simply answering questions rather than complaining (lines 20–21), and then finally makes explicit what appears to be the source of the offence she is taking at Gurmeet’s line of questioning, namely, his implicit assumption that he has the right to judge the situation of “her” country (lines 24–27).3

We can observe a number of metapragmatic comments in the above extract, which are indicated by the arrows, in relation to the construal of pragmatic acts (lines 17, 20–21), pragmatic meaning and accountability (line 22), and relational entitlements (lines 23–27). In lines 17 and 20–21, the elder disputes the way in which Gurmeet has framed her prior talk as complaining, and offers an alternative formulation of her actions as simply answering questions. In this case, it is the way in which her prior talk is being construed as a particular pragmatic act, namely “complaining”, that is at issue. Studies of complaints in English have shown that complaining is regarded as an inherently moral act, and thus to characterize some talk as “complaining”, involves the question of whether there are sufficient grounds for launching the complaint, and thus whether the person complaining has the right to make such a complaint (see Drew 1998). Such research has also shown that participants will often engage in considerable interactional work to avoid what they are meaning being construed as complaining (Edwards 2005).

In line 22, Gurmeet moves to hold the elder accountable for complaining rather than answering questions by invoking the sense of saying as meaning something In other words, Gurmeet construes the elder as previously implying that the situation of indigenous Australians has not been very good because of the actions of others (in particular, the Australian government). He thus attempts to hold her accountable for this particular reflexively intended assumption.

Finally, in lines 23–27, we can see the elder disputing Gurmeet’s right to evaluate and comment on the situation of indigenous Australians by construing herself as an “insider” and Gurmeet as an “outsider” to “Kamilaroi country” (where the Indians are currently visiting). In other words, she is explicitly referring to her entitlement to comment on the circumstances of “her people”, as opposed to the lack of such an entitlement on Gurmeet’s part, thereby alluding to issues of interpersonal relations and their respective “sociality rights”. It is also evident throughout that the elder is treating Gurmeet’s line of questioning as “inapposite”, if not outright offensive, thereby indicating an implicit orientation to a particular interpersonal attitude on the part of Gurmeet, namely, that he is being “impolite” or “offensive”.

In order to understand the above excerpt, however, it is evident that we also need to have a clear understanding of what these participants mean by such terms as complaint/complaining, asking questions, saying, and impolite/ offensive, as well as what these words mean for English speakers more generally, given the interaction was broadcast on television to an “overhearing” audience. Thus, while “technical” meanings can be ascribed to such terms, it is important to remember that this metalanguage means something to ordinary participants too.

الاكثر قراءة في pragmatics

الاكثر قراءة في pragmatics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة