Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 6-5-2022

Date: 2023-06-09

Date: 23-4-2022

|

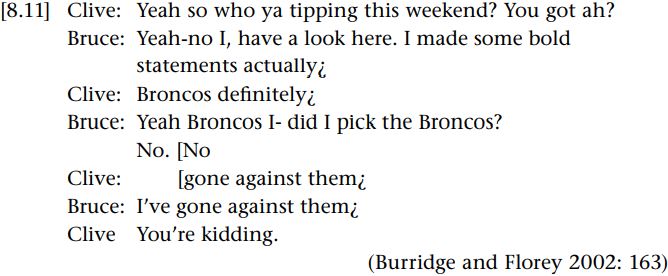

According to Burridge and Florey (2002), the pragmatic marker yeah-no is increasingly used by speakers of Australian English, although it is clearly not restricted to Australian English, as it can also be found in talk amongst speakers of other varieties of English. The basic function of yeah-no is to indicate reflexive awareness that there is more than one line of interpretation of current talk at play in the interaction (i.e. it is reflective of metacommunicative awareness on the part of users).

In the following excerpt from a conversation, two Australian friends are discussing football (specifically, rugby league), and who they are tipping (i.e. putting their bet on) for the upcoming game:

In this example, yeah-no is used by Bruce to indicate reflexive awareness of two possible lines of interpretation here. The first involves a “yeah-no” response to Clive’s trailing-off question (You got ah?) about whether Bruce has a team in mind to tip. Through responding yeah, Bruce indicates that he does have a tip in mind. At the same time Bruce also projects that his tip this time will not be in line with Clive’s expectations, by subsequently uttering no. This latter interpretation becomes clear when Bruce says that he is not going to tip for the Broncos (the name of a rugby league team in Brisbane). That this is counter to Clive’s expectations is apparent from his expression of surprise (You’re kidding). In other words, yeah-no is used here by Bruce to introduce a “surprise departure from his usual tipping practices” (Burridge and Florey 2002: 163), and so constitutes an example of an orientation to the metacognitive status of particular information that is assumed to lie in the common ground of Bruce and Clive, namely, Bruce’s usual tipping practices.

This pragmatic marker has been ironically adopted most infamously by Vicky Pollard, a satirical character on the British television series, Little Britain. She uses the catch phrase yeah but no but yeah but, and variants of it, to launch long rants where her breakneck speed of talk and the irrelevant information or gossip she offers is intended to confuse or annoy the recipient. Yeah-no is apparently being used by the comedian Matt Lucas, in the guise of Vicky, to invoke or comment on social discourses about “declining standards” of spoken English amongst younger generation speakers in Britain.

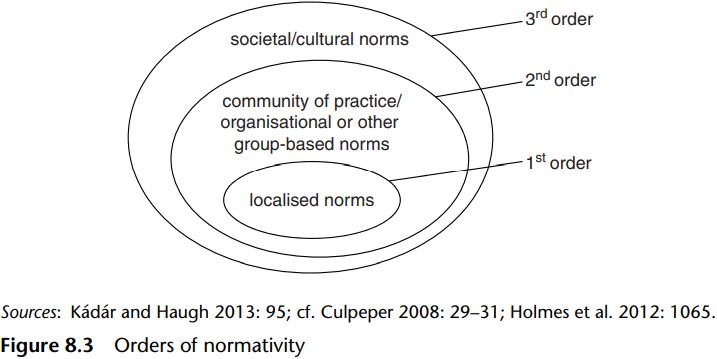

Such evaluations inevitably involve appeals to normative ways of thinking, speaking and doing things. Verschueren, for instance, argues that such normativity necessarily involves a “metalevel of awareness”, and it is at this level that “the norms involved are constantly negotiated and manipulated” (2000: 445). Silverstein (2003) goes further in proposing that these norms form what he terms orders of indexicality. This refers to the idea that normative notions about “how language works, and what it is usually like, what certain ways of speaking connote and imply” are reflexively layered. At the first layer (or fi rstorder) of norms we find probabilistic conventions for language use. These are formed for individuals through their own history of interactions with others, and so while they may be similar, they are never exactly the same across individuals. At the second layer (or second-order) we find localized ideologies and evaluations of language use. In other words, normative ideas about language use that are shared across particular social groups. Finally, at the third layer (or third-order) we find language conventions as they are represented in supra-local (i.e. societal) ideologies and evaluations of language use. In being ordered, it is not necessarily assumed that third-order norms will always take precedence over second-order ones and so on (although they often do), but rather that in invoking first-order norms we inevitably invoke second- and third-order ones as well. In pragmatics our specific concern is evaluative norms relating to language use, namely, assumptions “about what is ‘correct’, ‘normal’, ‘appropriate’, ‘well-formed’, ‘worth saying’, ‘permissable’, and so on” (Coupland and Jaworski 2004: 36), and how these cut across all three orders.

These ordered layers of normativity can be represented as in Figure 8.3. There it is suggested that the localized norms which develop for individuals or localized relationships are necessarily embedded (and thus interpreted) relative to communities of practice, organizational or other group-based norms, which are themselves necessarily embedded relative to broader societal or “cultural” norms. While all three layers of normativity can be studied, we would argue that they are most productively analyzed at the second-order level, namely, localized ideologies shared across identifiable communities of practice, organizations or other recognizable groups (see also Culpeper 2010, which argues for the middle, as in second-order, level with respect to historical sociopragmatics)

Consider, for instance, the following excerpt from a radio interview with the singer, Justin Bieber, which went horribly wrong when the interviewer, Mojo, made a joke about Harry Styles and Bieber’s mother:

Here the interactional trouble begins when the interviewer, Thomas “ Mojo” Carballot, teases Bieber about Harry Styles, who was reported in the news at the time to be dating older women, having an interest in Bieber’s mother. Bieber initially responds with a request for a repeat of the question, which is indicative of a possible challenge to the askability of that question, but when the question is essentially repeated by Mojo, Bieber then responds with a tease of his own about Mojo’s mother. After Mojo deflates Bieber’s tease in countering that his mother is already dead (and thus not someone with whom Harry Styles could be trying to date), there is a long ten-second silence, and then Bieber (apparently) hangs up. It was subsequently reported that when the technician tried to get Bieber back on the line to continue the interview that “He [Bieber] got a little upset with the question”.

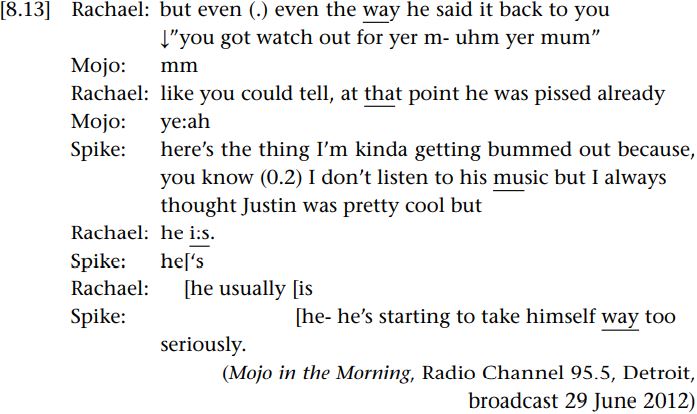

The following day Mojo discussed what went wrong in the interview with two other announcers, Rachael and Spike:

Here it is claimed by Rachael that Bieber’s initial tease (before hanging up) was indicative of him taking offence. The way Bieber dealt with the interview is then characterized by Spike as him taking himself too seriously, thereby casting the offence as not warranted.

We can analyze the metapragmatic comments by these two other observers in relation to the three different orders of normativity that we introduced above. At the first-order, or localized level, we can see in [8.12], about which they are commenting, how Mojo is evidently trying to establish a “joking” relationship with Bieber where this kind of “ribbing” or teasing is allowable. This reflects, in turn, second-order norms associated with the practices of radio “shock jocks”, such as Mojo, where guests are subject to joking, teasing, mocking and the like, and how celebrities, in particular, are expected to deal with that by not taking themselves “too seriously”. Finally, the negative assessment accomplished through casting Bieber as “starting to take himself way too seriously” in [8.13] invokes, in turn, third-order norms, namely, the social sanctions directed at those who take themselves “too seriously”, and the positive value placed on not taking oneself too seriously amongst Anglo speakers of English (see Fox 2004; Goddard 2009).

However, just because particular participants invoke these kinds of third-order norms, this does not mean to say that what counts as offensive or sanctionable behavior is not open to dispute by others. In the following post, after a report about the incident was published in the online version of the Daily Mirror, one user claimed that Mojo was being “rude”:

8.14]

That was rude for him to say if he worries about Harry around his mom he is just a kid not an adult. Mojo was wrong with the question. U all r adults expecting kids to act like adults. Inappropriate question! Grow up Mojo.

Here a different set of third-order norms are invoked, namely, what counts as (in) appropriate around adults versus kids, thereby challenging the secondorder normative practices of radio jocks such as Mojo.

Investigating localized, as well as second-order, ideologies is a useful way to better understanding the normative features of interaction that are so often treated as simply “commonsensical” and thus rarely questioned by users (Blommaert and Verschueren 1998). And it is this line of work that leads us into the analysis of metadiscursive awareness at the third-order level of normativity on the part of users (see Verschueren 2012 for a useful introduction to such work). This is not to say, however, that the pragmatic meanings and interpersonal relations and attitudes which arise in discourse through invoking such norms are not open to negotiation or dispute, as we saw above. Indeed, metapragmatic commentary can be strategically deployed for that very purpose, as we shall now discuss.

|

|

|

|

5 علامات تحذيرية قد تدل على "مشكل خطير" في الكبد

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

لحماية التراث الوطني.. العتبة العباسية تعلن عن ترميم أكثر من 200 وثيقة خلال عام 2024

|

|

|