Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Relational

المؤلف:

Jonathan Culpeper and Michael Haugh

المصدر:

Pragmatics and the English Language

الجزء والصفحة:

217-7

25-5-2022

927

Relational

Relational approaches have a central focus on interpersonal relations in common, rather than a central focus on the individual performing “politeness” which is then correlated with interpersonal relations as variables, as happens with Brown and Levinson (1987). This, in fact, has important implications. The term polite has been stretched, especially in the classic theories, to cover a range of different phenomena, not all of which would readily be recognized as polite by the lay person. In Britain, saying please or thank you would readily be recognized as polite, but would giving someone a compliment attract the same label? Perhaps the latter is just seen as an example of “nice”, “kind” or “supportive” behavior, or even “sneaky”, “manipulative” or “arse-licking” behavior. Of course, it is an empirical question as to what perceptions and labels particular behaviors attract, but there is no doubting that their discussions of politeness encompass such a breadth of phenomena that the label polite is unlikely to be the descriptor of choice for each individual phenomenon. Relational approaches avoid seeing everything through the prism of politeness. In point of fact, they also encompass impolite behavior. We will briefly outline the two main relational approaches, the relational work approach of Locher and Watts’ (e.g. Locher 2004, 2006; Locher and Watts 2005; Watts 2003) and the rapport management approach of Spencer-Oatey (e.g. 2008).

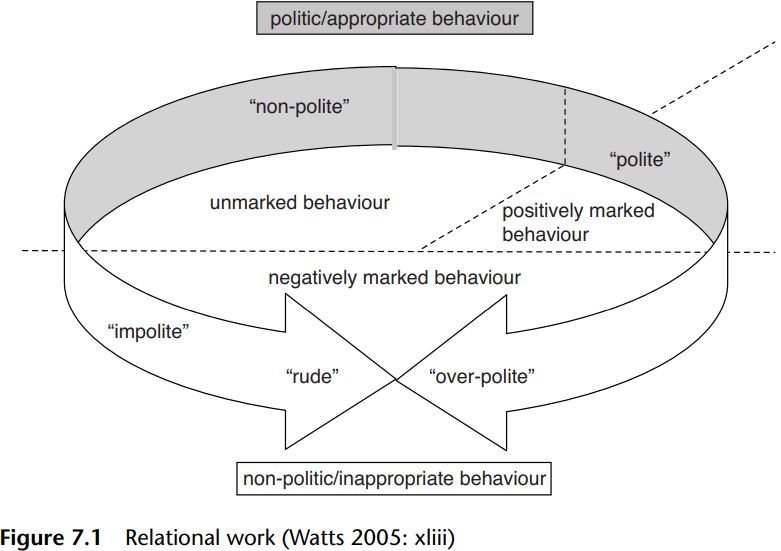

Locher and Watts state that “relational work can be understood as equivalent to Halliday’s (1978) interpersonal level of communication” (2005: 11) and, further, that “[r]elational work is defined as the work people invest in negotiating their relationships in interaction” (2008: 78). Relational work is not switched off and on in communication but is always involved. The concept of face is central to relational work, though not as defined by Brown and Levinson (1987) but by Goffman (1967: 5). Face is treated as discursively constructed within situated interactions. Watts (2005: xliii, see also Locher and Watts 2005: 12; Locher 2004: 90) offers a diagram which usefully attempts to map the total spectrum of relational work, reproduced in Figure 7.1.

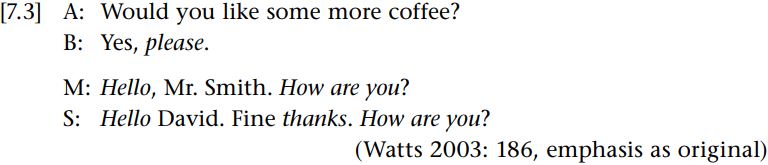

Relational work in this perspective incorporates the issue of whether behavior is marked or not. Markedness here relates to appropriateness; if the behavior is inappropriate, it will be marked and more likely to be noticed. Note that the notion of appropriateness can be viewed in terms of acting in accordance or otherwise with social norms. Unmarked behavior is what Watts (e.g. 2003) refers to in his earlier work as “politic behavior”: “[l]inguistic behavior which is perceived to be appropriate to the social constraints of the ongoing interaction, i.e. as non-salient, should be called politic behavior” (Watts 2003: 19), and is illustrated by the following examples:

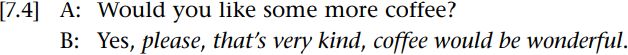

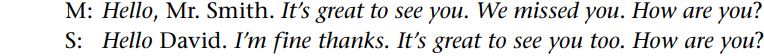

Politeness, on the other hand, is positively marked behavior. Watts (2003: 19) writes that “[l]inguistic behavior perceived to go beyond what is expectable, i.e. salient behavior, should be called polite or impolite depending on whether the behavior itself tends towards the negative or positive end of the spectrum of politeness”. By way of illustration, we can re-work Watts’s examples accordingly:

الاكثر قراءة في pragmatics

الاكثر قراءة في pragmatics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)