Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Speech acts in socio-cultural contexts

المؤلف:

Jonathan Culpeper and Michael Haugh

المصدر:

Pragmatics and the English Language

الجزء والصفحة:

175-6

17-5-2022

1143

Speech acts in socio-cultural contexts

One particular problem speech act theory has is its underestimation of the role of context, especially social context. Holdcroft (1994: 360–361), from his more philosophical perspective, highlights the issue through an example (VP = verb phrase):

Suppose that S is in a position of authority and that he has made it clear that he is going to give us instructions. In that case it would be much simpler to try to corroborate the hypothesis that S is requesting us to VP directly without going through Searle’s elaborate inference schema ... In other words the inferential process tries to corroborate the most likely hypothesis given the background assumptions, including crucially the conversational goals of the participants.

This idea is in tune with Levinson’s ([1979a] 1992) discussion of activity types; knowing the activity type of which an utterance is a part helps us to infer how that utterance should be taken (i.e. what the illocutionary point of the act is). More generally, the issue is that key interpersonal information is missing from Searle’s account (it is more salient in Austin’s account). This information alone can trigger a requestive interpretation, circumventing the Gricean inference process. Holtgraves (1994), for example, found that knowing that the speaker was of high status was enough to prime in one’s head a directive interpretation in advance of any remark having been actually made (see also Ervin-Tripp et al. 1987 and Gibbs 1981, for the general importance of social context in speech act interpretation). In other words, knowing the speaker is of high status makes it more likely that you will take what they say as a request, because high status is associated with requestive activity. Also, when non-conventional requests were made by high status speakers, the processing of those requests was quite similar to that of conventional requests (such as can you pass the salt?) – both involve associative inferencing circumventing the Gricean inferencing process. This would suggest that speech act theory needs to bring social information on board if it is to account for the inferencing related to indirect speech acts. Indeed, given that indirect requests are largely motivated by interpersonal considerations and that even Searle (1975: 76) admits that politeness is a key motivating factor, it seems odd that such considerations have been so studiously ignored.

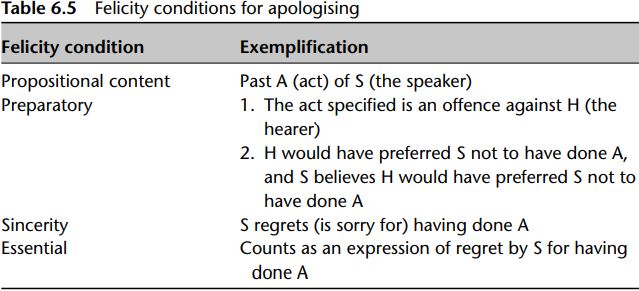

Another consideration that has been glossed over in accounts of speech acts is the influence of the broader cultural milieu in which they are performed. Speech acts are understood in different ways across languages and cultures. This point has been made most emphatically by researchers employing the Natural Semantic Metalanguage (NSM), which employs a core set of basic words that are claimed to have equivalents in all languages to define concepts, including speech acts, across cultures (Goddard 2006; Wierzbicka 1985, [1991]2003). Let us consider apologies, first approaching them in terms of traditional speech act theory and then NSM. The felicity conditions for performing an apology given in Table 6.5 are based on Owen (1983), who in turn drew from Searle’s (1969: 66–67) preliminary sketch of them.

The key felicity condition for apologies is generally regarded to be sincerity, namely, the speaker sincerely feeling bad about what s/he has done to the recipient (an apology is an expressive speech act, and the sincerity condition is key for all such acts).

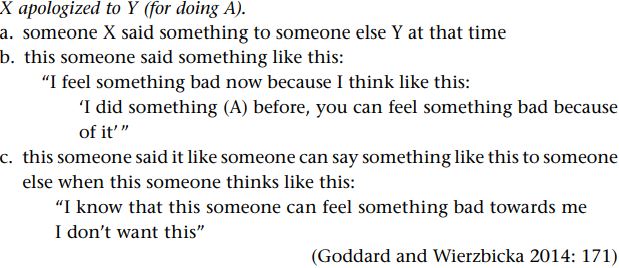

Turning to NSM, Goddard and Wierzbicka capture the meaning of the speech act verb apologize in English using semantic primes, semantic concepts that cannot be expressed in simpler terms and are claimed to be universal:

The emphasis here is on the speaker having done something that makes the recipient feel bad (an offence), and the speaker showing s/he feels bad about what has happened (sincerity). In other words, the speaker implies responsibility for doing something that (may have) made the recipient feel bad. Importantly, to apologize is something the speaker (nominally) chooses to do.

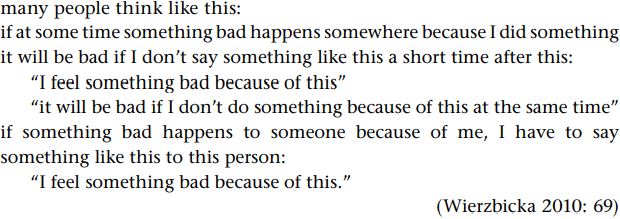

In Japanese, apology IFIDs, such as sumimasen (lit. to not finish or be satisfied) are used very frequently, including in situations in which an English speaker would generally expect “thanking” to occur. Wierzbicka (2010) suggests that one reason for this is that a different understanding of “apology” prevails in the form of the following cultural norm, which is characteristically (though not exclusively) Japanese:

Wierzbicka suggests that the use of an apology IFID in Japanese does not presuppose that the speaker has done something bad to the recipient per se, but rather that something potentially bad (or at least “not good”) from the perspective of the recipient has happened, which relates in some way to the speaker. This is why an “apology” IFID can be issued when thanking someone in Japanese, in order to highlight the inconvenience for the recipient of having proffered whatever has occasioned this thanking (Kumatoridani 1999). There is also a stronger expectation that the speaker will issue an apology in Japanese, as opposed to English (which explains the components “I have to say something like this” and “it will be bad if I don’t say something” in the Japanese script versus their absence in the English script). This means that one is expected to express something like sumimasen even when the inconvenience for the recipient is only indirectly related to the speaker’s actions.

One question that remains open, however, is whether such scripts are really able to capture all the pragmatic nuances of the use of such expressions. Sub - sequent work on “apologies” in Japanese has suggested they arise in the course of negotiating role-relations between participants (Long 2010). More specifically, they occur more frequently when “thanking” for something that lies outside of the participants’ role-relationship (or what is termed tachiba in Japanese). Further work on interactional shifts in the use of “apology” expressions has found they are not only deployed to avoid or end interpersonal “conflict”, but can also be used to index “attitudinal distance” (Sandu 2013). Thus, while the point is well taken that using English speech act verbs, such as apologize and its accompanying felicity conditions in analyzing “apologies” in Japanese, can be misleading, as it imposes an understanding that does not accurately reflect that of those speakers (Wierzbicka 2010), the alternative scripts appear to be overly reductive from a pragmatic perspective. In that sense, they constitute a good starting point, but not an end point, for analyses of pragmatic acts.

الاكثر قراءة في pragmatics

الاكثر قراءة في pragmatics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)