Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Directness/indirectness; explicitness/implicitness

المؤلف:

Jonathan Culpeper and Michael Haugh

المصدر:

Pragmatics and the English Language

الجزء والصفحة:

168-6

17-5-2022

1473

Directness/indirectness; explicitness/implicitness

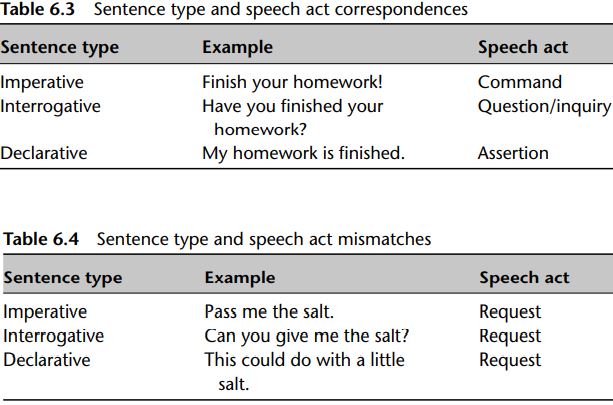

Searle (1969: 30) coined the term illocutionary force indicating devices (IFIDs) for the formal devices of an utterance used to signal its illocutionary force. We have already met a highly explicit IFID, namely, performative verbs. IFIDs need not be lexical or grammatical, a rising intonation contour is thought to have some kind of conventional association with speech acts that question or inquire. It is crucial, however, to remember that even with IFIDs there is no guarantee of a particular illocutionary force; that depends on the rest of the discourse and the context (e.g. I promise I’ll withhold your pocket money is a threat, not a promise, despite the IFID). The issue of form, and whether it matches a particular illocutionary force, is pertinent to the apparent correspondence between grammatical sentence type (or form) and speech act (or illocutionary force). In English there are three major sentence types which are associated with three speech acts, as displayed in Table 6.3.

The problem is that in present-day English there is frequently a mismatch between sentence type and speech act. Consider Table 6.4. Despite the mismatches between requests and the interrogative and declarative sentence types, it is not difficult to imagine contexts where these would count as requests. Note that they differ in terms of how directly the speech act is performed. Give me a hand is direct; Can you give me a hand? is indirect (in direct terms, it is a question about whether the addressee has the ability to give a hand); and I can’t do this on my own is off-record (i.e. a hint). The second example here fits Searle’s classic definition of indirect speech acts: “cases in which one illocutionary act is performed indirectly by way of performing another” (1975: 60).

However, there is little agreement on the status of direct/indirect speech acts or how indirect speech acts work (see Aijmer 1996: 126–128, for a brief overview), and some have even proposed that a scale of directness be dispensed with altogether (Wierzbicka 1991[2003]: 88–89).

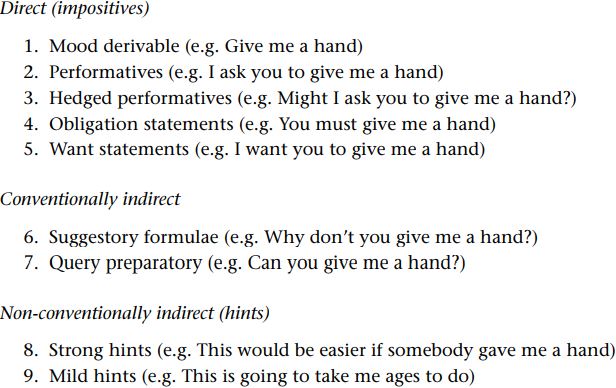

Perhaps the single most important application of speech act theory, and specifically the application of notions of indirectness to requests, is the work undertaken by Shoshana Blum-Kulka and colleagues (e.g. Blum-Kulka et al. 1989b) as part of the Cross-cultural Speech Act Realization Project (CCSARP’s). What is of particular interest to us here is how they systematized indirectness, because the approach affords insights into how indirectness works in requests. Blum-Kulka and her colleagues identified nine (in)directness strategy types. We give them in brief below (details can be found in Blum-Kulka et al. (1989b: 18), and the CCSARP coding manual in Blum-Kulka et al. (1989a: 278–281)):

It is worth noting, at this point, that requestive strategy taxonomies vary widely in the number of strategies they propose. Aijmer (1996: 132–133), for example, identifies 18. We cannot assume, therefore, that any set of strategies “fi t” any data. In addition, the term “direct” in Blum-Kulka’s work does not have the sense that Searle intended for it. If that were so, “obligation statements” (e.g. you must go now) and “want statements” (e.g. I want you to go now) would be considered indirect, as they are statements or assertions doing the job of requests. Instead, “directness” seems to refer to the explicitness with which the illocutionary point is signaled by the utterance, and complex processes of conventionalization or standardization feed that explicitness. Indeed, Blum-Kulka and House (1989: 133) refer to indirectness as “a measure of illocutionary transparency”.

In our view Searle’s (1975) notion of directness, essentially concerning (mis) matchings of syntax and speech act, only captures one aspect, though an important one, of what is going on with indirectness. Generally, we prefer the notion of pragmatic explicitness, which is based on the transparency of three things: the illocutionary point, the target and the semantic content. The transparency of the illocutionary point is roughly what Searle was talking about. This is essentially where a speech act is not achieved through its base sentence type or, more broadly, where one act is achieved through performing another; for example, saying one is busy (an assertion) to imply one cannot go to a party (a refusal). The transparency of the target can also increase directness. Compare Be quiet! with You be quiet! The latter example is more explicit in picking out the target through the use of you. And the transparency of the semantic content can also increase directness. Compare Be quiet! with Be noiseless! In this case, quiet has a closer match with the desired state than the circumlocution noiseless.

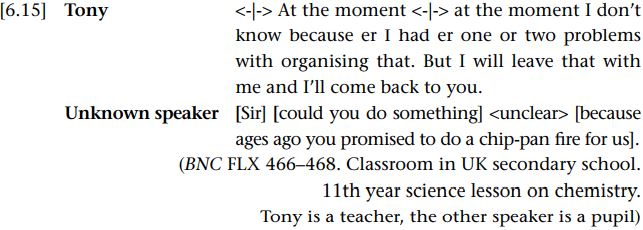

One particular contribution made by Blum-Kulka and colleagues was to widen the scope of their consideration of indirectness to include linguistic material working in conjunction with the central speech act utterance. They analyzed requests in terms of three major structural categories: the head act, alerter and support move (Blum-Kulka et al. 1989b). The second turn in example [6.15] provides an illustration (square brackets distinguish the categories):

The head act here is could you do something. This is the “minimal unit which can realize a request” (Blum-Kulka et al. 1989b: CCSARP coding manual: 275); if the other elements of the request were removed, it would still have the potential to be understood as a request. Sir functions as the alerter, “whose function it is to alert the hearer’s attention to the ensuing speech act” (Blum-Kulka et al. 1989b: CCSARP coding manual: 277), and also as a term of address expressing deference. Because ages ago you promised to do a chip-pan fi re for us is the support move and, more specifically, a grounder, giving grounds as to why the target should perform the action. Support moves can occur before or after the head act and their function is to mitigate or aggravate the request (Blum-Kulka et al. 1989b: CCSARP coding manual: 287).

It is worth noting that in some contexts the mere presence of a support move (without a head act) can be enough to trigger the inference that a request is being performed (the support move alone in the above example could have been interpreted as a request). This is not reflected in Blum-Kulka-inspired research, which has been overly preoccupied with head acts. In naturally occurring conversation things are rather more complex. For instance, requests are frequently elliptical. A parent commanding a child not to touch something may well say no, an expression which would not fi t any of Blum-Kulka’s categories.

الاكثر قراءة في pragmatics

الاكثر قراءة في pragmatics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)