Reflections: Explicit performatives in early modern English

المؤلف:

Jonathan Culpeper and Michael Haugh

المؤلف:

Jonathan Culpeper and Michael Haugh

المصدر:

Pragmatics and the English Language

المصدر:

Pragmatics and the English Language

الجزء والصفحة:

159-6

الجزء والصفحة:

159-6

17-5-2022

17-5-2022

859

859

Reflections: Explicit performatives in early modern English

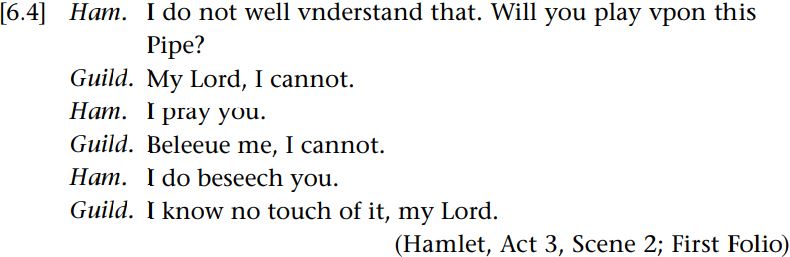

Explicit performatives were much more frequent in early modern English, especially as part of the grammatical frame FIRST PERSON PRONOUN + PERFORMATIVE VERB + SECOND PERSON PRONOUN (occasional optional elements include auxiliary do or adverbial elements). Thus we find I thank you, I warrant you, I assure you, I beseech you, I entreat you, I pray you and so on in abundance. With perhaps the exception of I assure you, all these are distinctly archaic today. I pray you is in fact the most frequent three-word collocational bundle in Shakespeare (and one that he uses more frequently than his contemporaries) (see Culpeper 2007). Consider the following excerpt from Shakespeare’s play Hamlet.

In this scene, Hamlet tries to persuade Guildenstern to play the pipe. Guildenstern’s reluctance can partly be explained by the fact that it is insulting for people of his standing to do so. I do beseech you is clearly an act of entreating. I pray you is a little trickier. Originally, it was an act of semi-religious supplication. However, as it came to be used frequently in conjunction with requests, its meaning bleached, so that it took on the sense of a politeness marker to facilitate requests. In fact, glossing I pray you with today’s please would not be wide of the mark

In his lectures, Austin first introduces the audience to performatives, and then moves on to a broader perspective. One step in this direction was the observation that utterances do not need a performative verb to perform an act (Austin 1975: 32ff.). Compare:

Both involve an act of promising; (a) is usually referred to as an explicit performative, and (b) an implicit performative (Austin 1975: 32). Another step was the observation that utterances could be viewed in terms of three different aspects, which we can simplify thus (for more detailed definitions, see Austin 1975: 94–132):

Locutionary act: “the act of saying something” (Austin 1975: 94; our emphasis); essentially, the production of an expression with sense and reference.

Illocutionary act: “the performance of an act in saying something” (ibid.: 99); essentially, the act the produced expression performs, such as informing, ordering, undertaking and sentencing (sometimes referred to as the illocutionary force of the utterance).

Perlocutionary act: “what we bring about or achieve by saying something” (ibid.: 109); essentially, the effects on the feelings, thoughts and actions of the participants brought about by the produced expression.

It is important to note here that Austin is separating meaning, traditionally defined in terms of sense and reference, from performing a function. For example, in a hot classroom a teacher might articulate to the student sitting next to the window the words It’s hot in here (locutionary act), and in saying this they perform an act of request (illocutionary act), with the effect that the student opens the window (perlocutionary act). Although speech act theory encompasses all three aspects, in subsequent work the notion of a speech act is virtually synonymous with illocutionary act (or illocutionary force). Speech acts include, for example, assertions, requests, commands, apologies, threats, compliments, warnings and advice.

Initially, Austin (1975: 3ff.) had distinguished performatives from what he called “constatives”, which are defined not in terms of “doing” but “saying”, statements being a paradigm case. However, crucially, towards the end of his lecture series, he revisited this distinction in a broader perspective (1975: 133ff.). Even statements in the form of declarative sentences, such as We are writing this topic, perform an act: they state or assert that a particular state of affairs applies. These too, then, perform an illocutionary act and, following on from that, an act that is subject to appropriate circumstances or felicity conditions. For example, stating something which you knew to be untrue would not meet the felicity condition of having the requisite thoughts. In the light of a general theory of speech acts, the distinction between performatives and constatives dissolves. Constatives have a performative aspect which we can refer to as their illocutionary aspect, just as the performatives discussed above do. What performative utterances have is a particular formal characteristic such that their verbs make explicit their particular illocutionary force.

الاكثر قراءة في pragmatics

الاكثر قراءة في pragmatics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة