Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Reflection: Defeasibility of inference versus cancellability of pragmatic meaning

المؤلف:

Jonathan Culpeper and Michael Haugh

المصدر:

Pragmatics and the English Language

الجزء والصفحة:

141-5

13-5-2022

875

Reflection: Defeasibility of inference versus cancellability of pragmatic meaning

Pragmatic inference differs from logical inference in that it is defeasible, which means such inferences allow for the possibility of error. In practice, this has been taken to mean that implicatures and other pragmatic meaning representations which derive from such inferences are cancellable (as we briefly discussed in the case of presuppositions). It is important to note that defeasibility is a characteristic of a cognitive process (e.g. pragmatic inference), while cancellability is a characteristic of the product of that process (e.g. an implicature). In practice, this means that while inferences can be blocked or suspended, implicatures can only be corrected/repaired (Haugh 2013b).

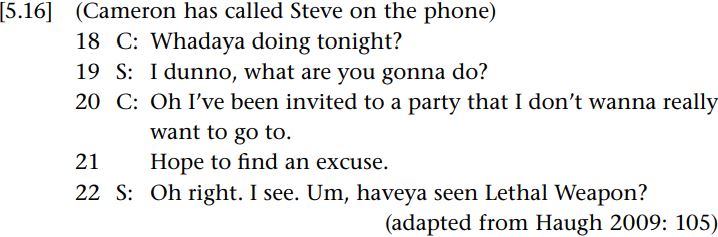

Blocking inferences involves cases where a potential inference (which could conceivably follow from what is said) is not allowed through by the speaker (an anticipatory orientation). For example, we can see in the utterance Some, in fact all, the people said they liked the food, that by adding in fact all after some, the putative “not all” scalar implicature is blocked from arising (Jaszczolt 2009: 261). Suspending inferences, on the other hand, involves cases where the speaker removes his/her commitment to an inference that has more than likely already been drawn (a retroactive orientation). For instance, in the following interaction on the phone between friends, what starts out as looking like Cameron will invite Steve to go out somewhere, ends up with Cameron hinting that he would like Steve to invite him out.

We can observe here how a (potential) default inference, which arises from Cameron’s utterance in line 18, namely that Cameron is very likely going to invite Steve somewhere if given a “go-ahead” response, is subsequently suspended by a nonce inference arising from Cameron’s subsequent utterances in lines 20–21, where it becomes apparent that he is hinting that he would like Steve to invite him somewhere. Steve obliges with an invitation in line 22. In this sense, then, we can see that pragmatic inferences are always contingent on what precedes and follows the utterance in question, and this is what makes them defeasible. We will return to consider this issue further.

To correct or repair an implicature, in contrast, involves denying, retracting or clarifying what was meant (normally by the speaker), or at least attempting to do so. We saw an example of this at the beginning (see example [5.1]). Defeasibility thus arises from cognitive operations on the part of individual users, while cancellability arises through social actions that are jointly achieved by participants.

الاكثر قراءة في pragmatics

الاكثر قراءة في pragmatics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)