Utterance-type meaning

المؤلف:

Jonathan Culpeper and Michael Haugh

المؤلف:

Jonathan Culpeper and Michael Haugh

المصدر:

Pragmatics and the English Language

المصدر:

Pragmatics and the English Language

الجزء والصفحة:

105-4

الجزء والصفحة:

105-4

9-5-2022

9-5-2022

2244

2244

Utterance-type meaning

A second key line of work amongst neo-Griceans relates to Levinson’s (1995, 2000) claim that we need to recognize a third layer of pragmatic meaning, namely, utterance-type meaning, which lies between what is said and utterance-token meaning (where the latter encompasses speaker-intended particularized conversational implicatures). Levinson argues that utterance type meaning involves representations that are not based on “direct computations about speaker-intentions but rather on general expectations about how language is normally used” (2000: 22). Many of the examples he lists are relevant to the analysis of pragmatic acts and social action (e.g. speech acts, felicity conditions, conversational pre-sequences, preference organization), and so do not constitute meaning representations per se because they do not involve the content of reflexively intended mental states (and for that reason will be discussed further). He does, however, list three examples of utterance-type meaning which do involve some kind of meaning representation, namely, presuppositions, conventional implicatures, and generalized conversational implicatures. To this we would add formulaic expressions in general.

The main focus of work on presumptive or utterance-type meaning amongst neo-Griceans has been on generalized conversational implicatures (GCI). Such work has usually involved explaining a specific set of quantity implicatures termed scalar implicatures (Horn 1984, 2009; Levinson 2000), as well as revisiting Grice’s conversational maxims in various ways. Scalar implicatures are claimed to arise through our assumed knowledge of underlying scales of degree, a point we touched upon in discussing contrastive focus. The most well-known example is the <all, most, many, some> scale, where some (and many and most) are treated as involving a relatively weaker epistemic claim than all. By uttering a relatively weaker value on a scale (e.g. some) a speaker can implicate by default, unless indicating otherwise, that he or she was not in a position to assert any stronger value (e.g. “not all”) (Horn 2009). For example, if someone asks me Who ate all the cake?, and I respond Well, I had some, then I have scalar implicated “[but] not all of it”.

There are many other scales which are claimed to also work in similar ways, such as those based on <and, or>, <the, a> , <always, usually, often, sometimes>, <certainly, probably, possibly>, or <hot, warm, cold> . For instance, if someone were to ask me whether the weather will be fi ne tomorrow for a planned picnic, and I respond probably, then, I have thereby scalar implicated that “I am not certain (it will be fine tomorrow)”.

We have already briefly touched on how the Givenness Hierarchy forms a scale that is the basis for implicatures arising from referents, but there are other types of GCIs that do not necessarily draw from such underlying scales. Levinson (2000), for instance, has developed a tripartite distinction between the principles of Quantity (“what isn’t said, isn’t”), Informativeness (“what is expressed simply is stereotypically exemplified”), and Manner (“what’s said in an abnormal way isn’t normal”) in accounting for generalized conversational implicatures. We can observe, for instance, two cases of GCIs arising through the Q[uantity]-principle in the following quote from (Senator and subsequently US President) Barack Obama.

Here, through Q-GCI, Obama not only admits that, when trying cigarettes as a kid, he inhaled frequently, thereby scalar implicating “not always”, but also, and perhaps more crucially, implicates “not as an adult”. The second implicature arises through the general principle of opposition in natural language, namely, that two attributes or positions can either be in “contrariety” (e.g. an adult versus a child) or in “contradiction” (e.g. an adult versus not an adult) (Horn 1989). In this case, mentioning something done “as a kid” implicates negation of the contrary (i.e. “not as an adult”). Or as Levinson (2000), puts it, “what isn’t said, isn’t”.

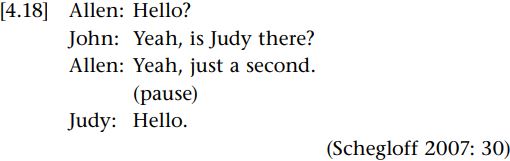

As we briefly noted previously, however, utterance-type meaning involves not just GCIs but other kinds of formulaic meanings. The ubiquity of formulaicity in language use was recognized early on by neo-Griceans who proposed the notion of “short-circuited implicature” (SCI), to account for meaning representations that are implicated through “relevant usage conventions” (Horn and Bayer 1984: 404; see also Morgan 1978). Consider the following example transcribed from a recording of a telephone conversation between two American speakers of English, which is a typical opening to such conversations:

John asks whether Judy is present to which Allen responds by confirming she is and then going off to fetch her. It is evident that both John and Allen have understood John’s question to mean more than what is said here, specifically, John has implicated that he would like to speak to Judy. Opening a telephone call with “Is X there?” is a recurrent way of implicating in English that we would like to talk to someone other than the person who has answered the phone (the activity type of making telephone calls is what constrains the range of plausible interpretations here). Yet it is not a given that by uttering “Is X there?” one will implicate this, even in the more narrowly circumscribed context of making telephone calls. If it were the case, for example, that Allen knows that John doesn’t like Judy, John might be understood as implicating (by flouting the relevance maxim) that he wants to talk to Allen without Judy overhearing. But this is a rather special case, and in most situations, “Is X there?” will indeed implicate something like “I want to speak to X”.

Such usage conventions abound, including routine expressions that require some kind of minimal context for the pragmatic meaning to arise. Routine expressions, or what Kecskes (2002, 2008) terms “situation-bound utterances”, include such expressions as tell me about it (which is standardly taken to mean an emphatic expression of agreement), come again? (standardly taken to mean the speaker is asking the hearer to repeat what has just been said, which may thereby also implicate scepticism or doubt about what has just been said), I was held up (standardly taken to mean the speaker was delayed due to circumstances outside of his or her control), help yourself (standardly taken to mean the hearer should feel free to choose and take what he or she wants), or no worries (standardly taken to mean the speaker does not have any negative feelings about a possible imposition or offence on the part of the hearer). Yet, while routine expressions standardly implicate something, they can, of course, be used in the literal sense as well. Routine expressions thus form another part of the layer of utterance-type meaning representations that Levinson (1995, 2000) describes, and to which we will return when we outline the frame-based approach to politeness, and particularly politeness formulae.

الاكثر قراءة في pragmatics

الاكثر قراءة في pragmatics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة