Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Deixis

المؤلف:

Jonathan Culpeper and Michael Haugh

المصدر:

Pragmatics and the English Language

الجزء والصفحة:

21-2

23-4-2022

2374

Deixis

We now turn to deixis, the category at the bottom of Table 2.1; we will discuss anaphora in the section following this one. Deixis relies heavily, though not completely, on the extralinguistic context to supply the referent, and not semantic elements within the deictic expression itself. It may be helpful to note here that the word deictic is borrowed from the Greek δεικτικ-ός ( deiktikos), meaning “able to show, showing directly”. Deixis involves connections between a reference point and aspects of the situation in which the utterance takes place; deictic expressions invite participants to work out particular connections. When somebody telephones another and says it’s me, they invite the interlocutor to work out, on the basis of oral characteristics, that me refers to the speaker. Occasionally, of course, the speaker’s assumptions that the interlocutor can work out who is speaking turn out to be wrong, and the interlocutor has to ask explicitly who it is (something which is potentially embarrassing, because the speaker assumed that you were sufficiently familiar with them to identify them). Consider another example, this time provided by Charles Fillmore (1997: 60):

Who is me? Where is here? When is tomorrow? And how big is this? Examples such as this neatly illustrate how one’s understanding depends on making connections between a reference point – that is, a deictic centre or anchorage point – from which the speaker positions their discourse and a particular context. If we cannot make these connections, we end up with very limited understanding.

The deictic centre is generally the I-here-now of the speaker, or, more accurately, of the speaking voice in the particular situation. The speaking voice could be that of, for example, an individual, a group of people, or a character in a book. Deictic expressions signal a perspective relative to a particular deictic centre (e.g. your “you” is my “I”; your “here” is my “there” etc.). In conversation, the deictic centre obviously fl ips back and forth according to who is speaking. The deictic centre can also be projected. If somebody rings you up and invites you over for some coffee, you may reply: I’ll come over in a few minutes. Come is a deictic verb, as it suggests the movement of something in the context towards the deictic centre. In this case, the deictic centre is not that of the speaker but that of the addressee. This is a case of deictic projection: the speaker projects the deictic centre onto the addressee and speaks from the point of view of the addressee.

A key point about deictic expressions is that they interface with grammatical systems. This feature is brought out in Levinson’s (1983: 54) definition of deixis:

Deixis concerns the ways in which languages encode or grammaticalise features of the context of utterance or speech event, and thus also concerns ways in which the interpretation of utterances depends on the analysis of that context of utterance.

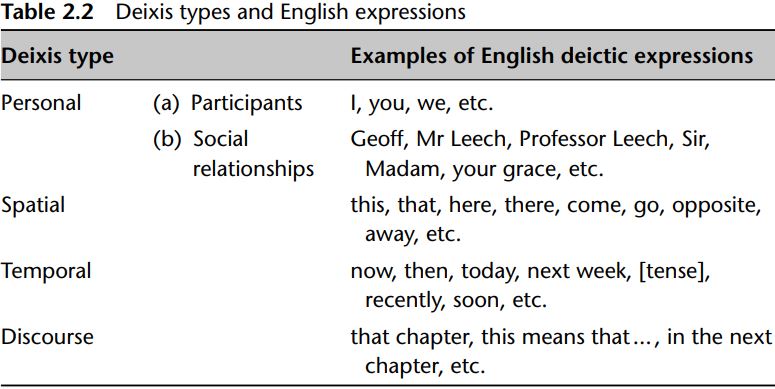

Expressions such as I, me and my are most clearly part of grammatical systems (we shall see in a moment how the context of utterance has not always been grammaticalised in the same way in earlier periods of English). Table 2.2 displays the types of deixis traditionally identified and their associated expressions.

Of course, deictic expressions can be used non-deictically. Consider the underlined items in these sentences:

Here, you is a generic usage, not referring to anyone in particular (it is similar to “one never knows”); there does not pick out a particular location, but is a case of “existential there”, that is to say, a kind of dummy subject which occurs in clauses about the existence or occurrence of something; finally, I, me and my do not refer to the speaker, as they are (metalinguistic) mentions of the pronoun rather than uses of them. As Fillmore (1997) points out, even demonstratives, a category that seems to be the purest category of deictic items, in fact have both deictic and non-deictic usages. Gestural usages, such as this foot, are supported by a gesture like pointing; they are deictic.

Symbolic usages, in contrast, rely on general spatio-temporal knowledge; they could be accompanied by a gesture, but would still be understood without. For example, in this newspaper headline Technology: Let’s make this country the best (The Guardian, 1/9/13), it will be obvious to most UK-based Guardian readers that this country refers to the UK, without gestures. The converse is also true: typically non-deictic expressions can be used deictically. For example, he or she would not normally be discussed as deictic expressions, as they are typically anaphoric, referring back to something mentioned previously in the discourse rather than connecting with the extralinguistic context (we will discuss anaphora in the following section). But it is not too difficult to imagine a context in which they clearly have a deictic referring function. Consider a (reconstructed) conversation during which a parent brings a crying baby into the room and an interlocutor says:

We should also keep in mind the fact that items within categories, such as those of Table 2.1, vary with respect to the degree to which they are semantically descriptive and contextually pragmatic. For example, here indicates the speaker’s spatial deictic centre, but come also encodes the meaning of locomotion towards it.

Let us elaborate on the particular categories of Table 2.2. Personal, as a deictic category, refers to the identification of three discourse roles in the speaking situation: the speaker (the first person), the hearer (the second person), and the party being talked about (the third person). Person is a hugely important grammatical category. First, second and/or third person is marked or implicit in all utterances. An indication of its importance in English is in the fact that the second most frequent word in spoken English is I and the third is you (Leech et al. 2001: 144) (as we noted earlier, the most frequent is the). Personal deixis invites participants to identify the relevant discourse role(s) in the context.

Person markers are not devoid of encoded meaning. In fact, they rarely encode person alone, but also have other grammatical distinctions. In English, these are number (e.g. I vs. we), gender (e.g. he vs. she) and case (e.g. she vs. her). Note here that deictic person markers are typically the first and second persons, not the third. Third person forms are generally anaphoric, that is, not extralinguistic but referring back to the linguistic co-text of the utterance, though, as illustrated in the previous paragraph, third person forms can be used deictically.

الاكثر قراءة في pragmatics

الاكثر قراءة في pragmatics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)