Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Clauses

Part of Speech

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Direct and Indirect speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Denotation, sense, reference and deixis

المؤلف:

Patrick Griffiths

المصدر:

An Introduction to English Semantics And Pragmatics

الجزء والصفحة:

11-1

10-2-2022

2990

Denotation, sense, reference and deixis

Expressions – sentences, words and so forth – in a language were said to denote aspects of the world. The denotation of an expression is whatever it denotes. For many words, the denotation is a big class of things: the noun arm denotes all the upper limbs there are on the world’s people, monkeys and apes. (Yes, there is a noun arms that has a lot of weapons as its denotation, but it always appears in the plural form.) If expressions did not have denotations, languages would hardly be of much use. It is the fact that they allow us to communicate about the world that makes them almost indispensable.

Because languages have useful links to the world, there is a temptation to think that the meaning of a word (or other kind of expression) simply is its denotation. And you would stand a chance of elucidating the meaning to someone who did not know the body part meaning of arm by saying the word each time as you point to that person’s arms, one at a time, and wave one of your own arms then the other. In early childhood our first words are probably learnt by such processes of live demonstration and pointing, known as ostension. It is not plausible as a general approach to meaning, however, because:

. It ignores the fact that after early childhood we usually use language, not ostension, to explain the meanings of words (“Flee means ‘escape by running away’”).

. When people really do resort to ostension for explaining meanings, their accompanying utterances may be carrying a lot of the burden. (“Beige is this color” while pointing at a piece of toffee; or think of the legend near a diagram in a book indicating what it is that one should see in the diagram. It would be easier to avoid the misunderstanding that the word arm means ‘move an upper limb’ if you produced sentence-sized utterances: “This is your arm”, “This is my right arm” and so on, while doing the pointing and showing.)

. There are all kinds of abstract, dubiously existent, and relational denotations that cannot conveniently be shown. (Think of the denotations of memory, absence, yeti and instead of. These are only a tiny sample of a large collection of problems.)

There are two general solutions, which are compatible, but differ in their preoccupations. The most rigorous varieties of semantics (called formal semantics because they use systems of formal logic to set out descriptions of meaning and theories of how the meanings of different sorts of expressions are constructed from the meanings of smaller expressions; see Lappin 2001) accord importance to differences between kinds of denotation. Thus count nouns, like tree, may be said to denote sets of things (and it is the denotation being a set that is of interest, rather than what things are in the set); property words, like purple, also denote sets (sets of things that have the property in question); singular names denote individuals; mass nouns, like honey, denote substances; spatial relation words, like in, denote pairs of things that have that spatial relation between them; the most straightforward types of sentence, like Amsterdam is in Holland, can be analyzed as denoting either facts or falsehoods; and so on.

Another approach, which I believe is a valuable start in the linguistic study of meaning, will be presented in a version that forms a reasonable foundation for anyone who, later, chooses to learn formal semantics. In this approach the central concept is sense: those aspects of the meaning of an expression that give it the denotation it has. Differences in sense therefore make for differences in denotation. That is why the term sense is used of clearly distinct meanings that an expression has. Example (1.7), for instance, illustrated two senses of conductor, and a third sense of this word denotes things or substances that transmit electricity, heat, light or sound.

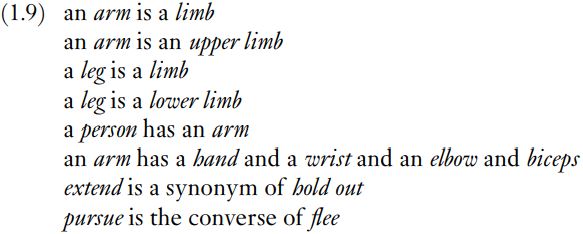

There are different ways in which one might try to state “recipes” for the denotations of words. One way of doing it is in terms of sense relations, 4which are semantic relationships between the senses of expressions. This is the scheme that is going to be used. It harmonizes well with the fact that we quite commonly use language to explain meanings. In (1.9) some examples of items of semantic knowledge we have from knowing sense relations in English are listed. Notice that they amount to explanations of meanings.

Sense relations between words (and some phrases, such as upper limb in (1.9)) will be further explained and illustrated, dealing successively with adjectives, nouns and verbs. The reason for thinking that such ties between senses have a bearing on denotation is the following: with words interconnected by well-defined sense relations, a person who knows the denotations of some words, as a start in the network of relationships, can develop an understanding of the meanings (senses) in the rest of the system.

Reference is what speakers or writers do when they use expressions to pick out for their audience particular people (“my sister”) or things (“the Parthenon Marbles”) or times (“2007”) or places (“that corner”) or events (“her birthday party”) or ideas (“the plan we were told about”); examples of referring expressions have been given in brackets. The relevant entities outside of language are called the referents of the referring expressions: the person who is my sister, the actual marble frieze, the year itself, and so on. Reference is a pragmatic act performed by senders and interpreted at the explicature stage. Reference has to be done and interpreted with regard to context. Consider (1.10) as something that might have been written in a letter.

The letter writer would have to be sure that the recipient knows they live in Indiana – where there is an Edinburg – if the utterance is not to be misunderstood as about a trip to the Edinburg in Illinois, or the one in Texas, or even Edinburgh in Scotland. When using the pronoun we, the writer of (1.10) refers to herself, or himself, and associates. The recipient of the letter can work out the reference by knowing who wrote it and can pragmatically infer the time reference of “today” from knowledge of when the letter was written. Imagine, however, that the letter is eventually torn up and a stranger finds a scrap, blowing in the wind, with only (1.10) on it. Uncertain about the situation of utterance, the stranger will not know who the travelers were, which Edinburg they drove to, or when they did so.

Deictic expressions are words, phrases and features of grammar that have to be interpreted in relation to the situation in which they are uttered, such as me ‘the sender of this utterance’ or here ‘the place where the sender is’.

A course bulletin board once carried a notice in Week 1 of the academic year worded as in (1.11).

The notice was not dated and the tutor forgot to take it down. Some students who read it in Week 2 failed to attend the Week 2 tutorial meeting because “next week” had by then become Week 3. Next week is a deictic expression meaning ‘the week after the one that the speaker or writer is in at the time of utterance’.

Deixis5 is pervasive in languages, probably because, in indicating ‘when’, ‘where’, ‘who’, ‘what’ and so on, it is very useful to start with the coordinates of the situation of utterance. There are different kinds of deixis, relating to:

time: now, soon, recently, ago, tomorrow, next week

place: here, there, two Kilometres away, that side, this way, come, bring, upstairs

participants, persons and other entities: she, her, hers, he, him, his, they, it, this, that

discourse itself: this sentence, the next paragraph, that was what they told me, I want you to remember this …

Our semantic knowledge of the meanings of deictic expressions guides us on how, pragmatically, to interpret them in context. Thus we have yesterday‘ the day before the day of utterance’, this ‘the obvious-in-context thing near the speaker or coming soon’, she ‘the female individual’ and so on. As always in pragmatics, the interpretations will be guesses rather than certainties: when you infer that the speaker is using the word this to refer to the water jug he seems to be pointing at, you could be wrong; perhaps he is showing you the ring on his index finger.

Deixis features in the account of metaphor. Tense (for instance, past tense told, in contrast to tell) is deictic too. More will be said about reference.

الاكثر قراءة في pragmatics

الاكثر قراءة في pragmatics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)