Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Clauses

Part of Speech

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Direct and Indirect speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Clitic pronouns or agreement?

المؤلف:

PAUL R. KROEGER

المصدر:

Analyzing Grammar An Introduction

الجزء والصفحة:

P325-C17

2026-02-14

18

Clitic pronouns or agreement?

Many languages have clitic pronouns, whether as the only available form (like the nominative and genitive pronouns in Tagalog) or as allomorphs of corresponding free pronouns, as in Indonesian. In Tagalog, it is clear that the nominative and genitive pronouns are clitics and not affixes; they always occur in second position regardless of where the verb is. But in many other languages, clitic pronouns are always attached to the verb or auxiliary. In this case, it can be very difficult to tell whether the bound forms are actually clitics (syntactically independent pronouns) or affixes (agreement markers).

As Givo̒n (1976) and others have pointed out, clitic pronouns often develop into agreement markers as languages change over time. As a result, we sometimes encounter intermediate forms with mixed properties, which can be very difficult to classify. But it is important to try to distinguish between clitic pronouns and agreement affixes wherever possible. Here are a few criteria which can help:

(i) if the bound forms sometimes attach to words other than the verb which selects them, they are almost certainly clitic pronouns; if they are always attached to the verb, they could be either clitic pronouns or agreement markers.

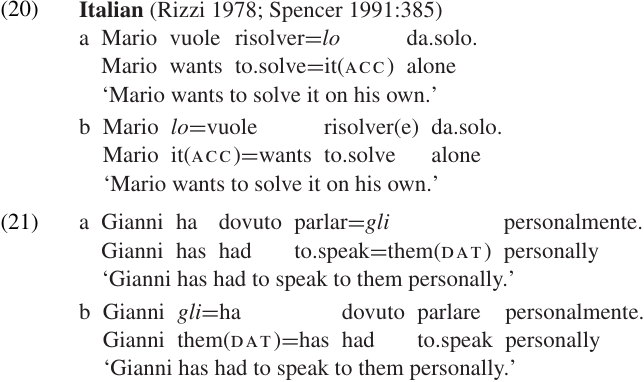

For example, object pronouns in Italian (as in Spanish) generally appear as clitics attached to the verb which assigns their semantic role. In certain constructions, a clitic pronoun which functions as the object of a subordinate verb can optionally appear before the main verb of the sentence (20b, 21b). Spanish is similar, as illustrated in (19). This pattern is often referred to as “clitic climbing,” since the clitic appears to “climb” up to a higher verb. This pattern constitutes strong evidence that the clitic forms are true pronouns, rather than agreement affixes.

(ii) if the bound forms are in complementary distribution with free pronouns (or full NP arguments), they are more likely to be clitic pronouns; if they can co-occur with free pronouns (or full NP arguments), they are more likely to be agreement markers.

(iii) if the bound forms occur inside (i.e. closer to the verb root than) one or more inflectional affixes, they are almost certainly agreement markers.1 Clitics do not normally invade the word boundary of their host.

(iv)if the bound forms are obligatory, they are more likely to be agreement markers.

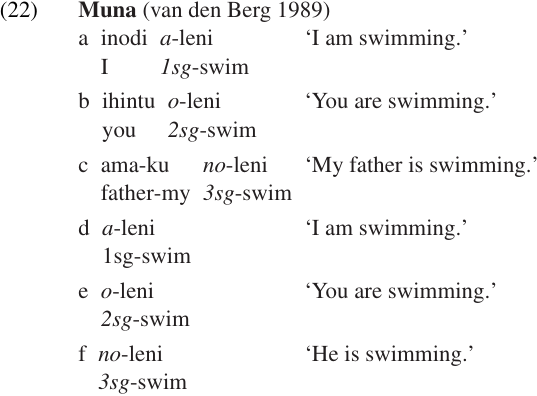

To take a concrete example, let us consider the Muna language of southern Sulawesi, Indonesia. A transitive verb in Muna can carry both a subject-marking prefix and an object-marking suffix. The subject marker is obligatory, occurring whether or not there is an overt subject NP in the sentence.2 This suggests that the subject markers are agreement affixes, rather than clitic pronouns.

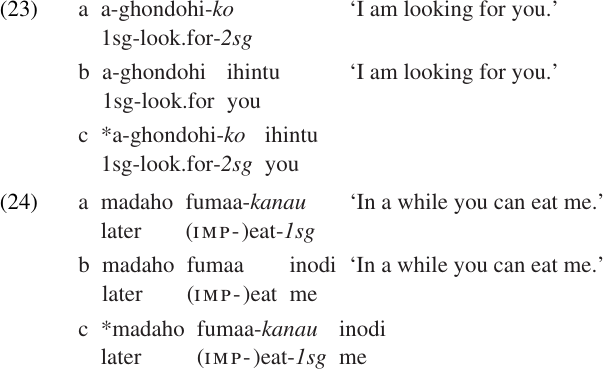

The behavior of the object suffixes is different in several ways. First of all, the object-marking suffixes are in complementary distribution with free object pronouns. That is, a transitive clause may contain either an object suffix or an object pronoun, but not both:

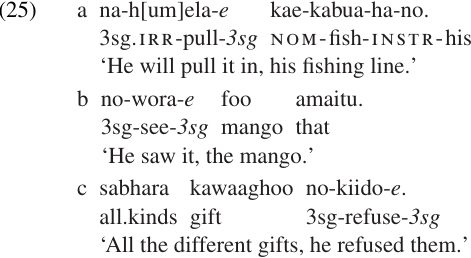

The object markers may co-occur with a full NP object phrase, as in (25a, b), but when they do the construction seems to involve a kind of apposition.3 Van den Berg (1989:164) states: “In most of the [se]cases...the direct object [NP] is a known entity that is supplied for the sake of clarification, almost as an afterthought.” This strongly suggests that the verb’s object “suffix” is actually a pronoun, and it is this pronoun which bears the OBJ relation. The “object” NP is actually a kind of appositional or adjunct phrase. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that, when the object NP is topicalized (moved to a pre-verbal position), as in (25c), the verb normally carries an object “suffix” as well.

So, while the subject-marking prefixes in Muna have the properties we expect of agreement affixes, the object markers seem more like clitic pronouns. A very similar pattern is reported in the Bantu language Chichewa (Bresnan and Mchombo 1987).

As we have mentioned on several occasions, our analysis needs to be based on a cluster of criteria. No one type of evidence taken by itself will be a reliable indicator. For example, the complementary distribution mentioned in point (ii) is an important characteristic of clitic pronouns, but there are certain well-known cases where this test breaks down. In Spanish (and a number of other languages) clitic pronouns may be co-referential with independent NPs, provided those NPs are marked by a preposition. This will normally be the case for recipients (OBJ2) or definite animate objects.

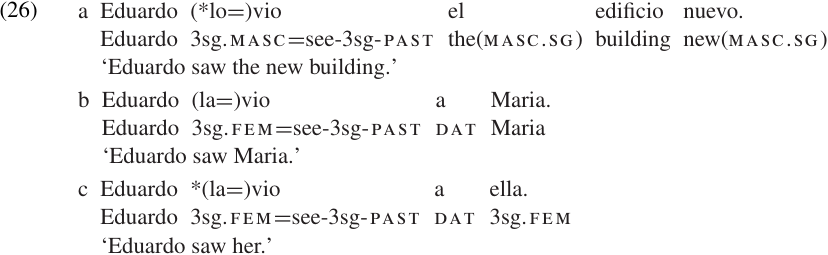

The co-occurrence of a clitic pronoun with a co-referential NP argument is called clitic doubling. Halpern (1998) states that CLITIC DOUBLING in Spanish is impossible when the object is a bare NP (26a), optional when the object is a dative NP (26b), and obligatory when the object is a free pronoun (26c).

So we need to consider a variety of evidence and adopt the analysis which best accounts for the whole range of data. The general principle here is that agreement markers will tend to have properties we expect to find in inflectional categories, while clitic pronouns tend to have properties we expect to find in arguments.

1. Apparent counter-examples to this generalization are found in Portuguese, Polish, and a number of languages in Sulawesi, including Tabulahan and perhaps Muna.

2. The use of independent pronouns as subjects in Muna seems to give special emphasis to the subject NP.

3. Two NPs are in apposition when they refer to the same participant in the same function or role within the clause (as opposed to, for example, reflexives); see Noun classes and pronouns.

الاكثر قراءة في Pronouns

الاكثر قراءة في Pronouns

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)