Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Clauses

Part of Speech

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Direct and Indirect speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Split ergativity

المؤلف:

PAUL R. KROEGER

المصدر:

Analyzing Grammar An Introduction

الجزء والصفحة:

P107-C7

2025-12-26

376

Split ergativity

In some languages we find both the ergative and accusative case marking patterns. For example, pronouns may take Nominative–Accusative marking while common nouns take Ergative–Absolutive marking; or animate nouns may take Nominative–Accusative marking while inanimate nouns take Ergative–Absolutive marking.

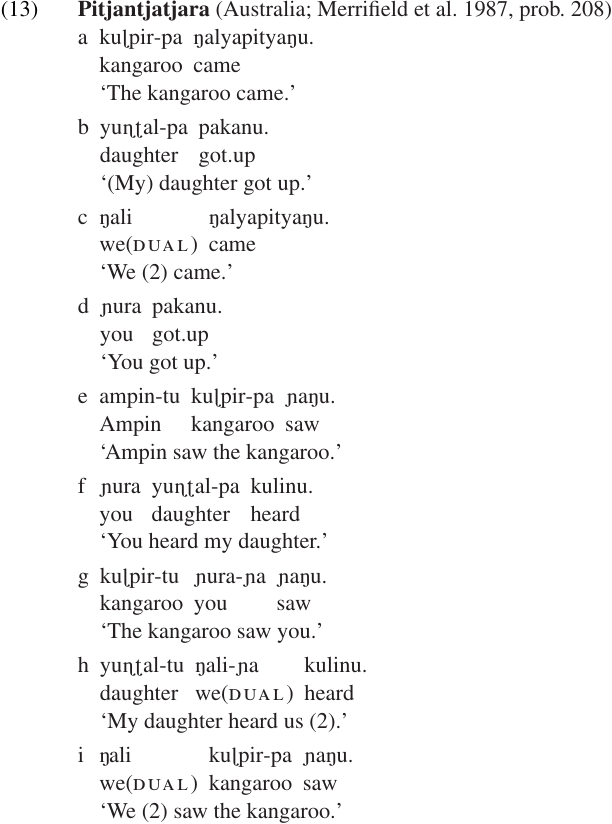

The term “SPLIT ERGATIVITY” refers to a situation in which both ergative and non-ergative patterns are found in the grammar of a single language. In other words, one subsystem the grammar follows an ergative pattern while a different sub-system does not. A typical example is found in Pitjantjatjara, another Australian language:

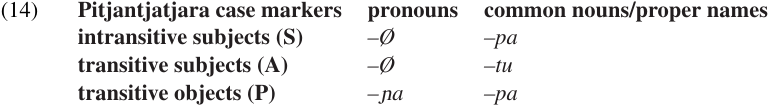

The case endings for nouns and pronouns are listed in (14). This chart shows that pronouns follow a Nominative–Accusative pattern, with the same (zero) case marker being used for intransitive subjects and transitive subjects and a different marker (-ɲa) being used for transitive objects. Common nouns and proper names, on the other hand, follow an ergative pattern, with the same case marker (-pa) being used for intransitive subjects and transitive objects and a different marker (-tu) being used for transitive subjects.

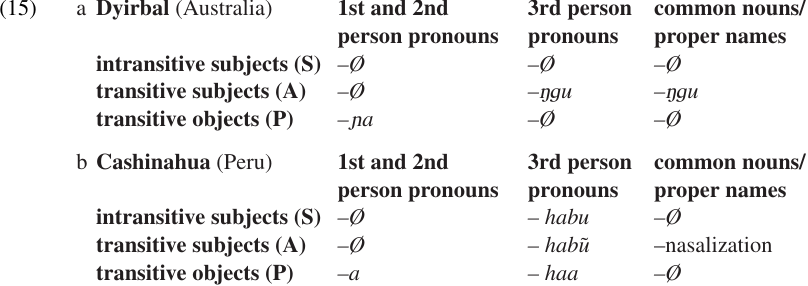

Some further examples of split-ergative case-marking systems, taken from Dixon (1979:87), are listed in (15). The Cashinahua third person pronouns illustrate a TRIPARTITE pattern, in which three distinct forms occur (15b).

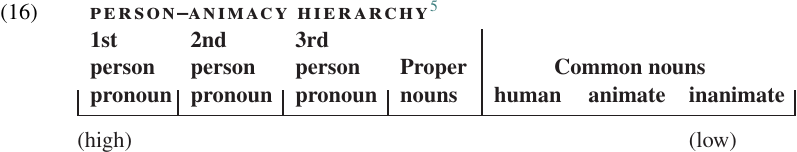

These examples illustrate split systems based on the PERSON–ANIMACY HIERARCHY, which is shown in (16). In almost every instance of split ergativity in which case marking is based on the inherent properties of the noun phrases themselves, categories near the left (= higher) end of the scale will follow the accusative pattern, while categories near the right (= lower) end of the scale will follow the ergative pattern. The dividing point between the two patterns, however, varies from language to language, as we have already seen.

It is tempting to ask why languages should be so consistent in this respect. One might suppose that it would be just as easy for pronouns to follow the ergative pattern while common nouns follow the accusative pattern, or for proper names to follow one pattern while all other NPs follow the other; but this does not seem to happen. A number of authors have suggested that the motivating factor is the relative likelihood of a participant’s functioning as agent vs. patient. Since inanimate objects rarely function as transitive agents, this is the situation that requires a distinctive marker (ergative case). Human participants (e.g. those generally named by first and second person pronouns) frequently serve as agents, so what is uniquely marked is the situation where they serve as patients (accusative case).6

This explanation seems quite plausible in the case of inanimate common nouns, but it is not so persuasive as a basis for distinguishing pronouns from proper names, or first and second person pronouns from third person animate pronouns, all of which seem equally likely to function as agents. Moreover, as pointed out by Wierzbicka (1981), frequency alone cannot be the relevant factor.7 There is no reason to think that first and second person pronouns occur more often as agents than patients in natural speech; Wierzbicka suggests that the opposite may, in fact, be true, at least for the first person. Perhaps a more general concept of “newsworthiness” would prove more useful than raw frequency. A speaker will take a special interest in events that affect himself (first person) or other people with whom he can identify (including the addressee, second person). This inherent interest may help to explain the tendency to mark these participants in a special way when they are affected by an action, i.e. when they occur as patients.

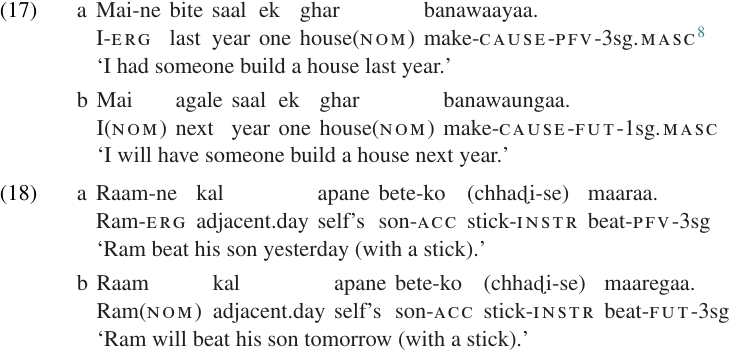

Split ergativity can also be conditioned by tense or aspect. Hindi is a well-known case. As the examples in (17–18) show, the case marking of the transitive agent depends on aspect: it takes ergative case when the verb is marked for perfective aspect, nominative in other aspects. Note that the ergative case marker-ne is distinct from both the genitive (-ka) and instrumental (-se). This is interesting because in many languages ergative case marking is identical to either the genitive or the instrumental.

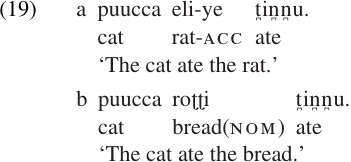

Based on this very small sample of data, can we say anything about the case marking of direct objects in Hindi? At first glance, the evidence seems to be contradictory: the object takes accusative case in (18), but nominative case in (17). It turns out that the case marking of objects is sensitive to animacy: accusative case is used only for animate objects, a pattern consistent with our discussion of the animacy hierarchy above. This pattern is found in a number of widely scattered languages, but is especially characteristic of south Asian languages, including Malayalam. Note the following contrast (Mohanan 1982:539):

This contrast is obligatory. Sentence (19a) would be un grammatical if the nominative form of ‘rat’ were used, because ‘rat’ is animate. Sentence (19b) would be un grammatical if the accusative form of ‘bread’ were used, because ‘bread’ is inanimate.

5. The relative ordering of 1st vs. 2nd person pronouns cannot be justified on the basis of split ergativity alone. However, the person–animacy hierarchy is relevant to a number of other construction types as well, such as the INVERSE systems of many North American languages, in which this ordering is clearly motivated.

6. This proposal was first developed by Silverstein (1976); Comrie (1978); and Dixon (1979).

7. Wierzbicka (1981:67) suggests that the hierarchy effect in split case-marking systems can be explained in terms of “inherent topic-worthiness.” She also makes the very helpful point that it is as experiencer, rather than agent, that the speaker enjoys a unique status.

8. Note that the verb in this example agrees with the nominative object, rather than the ergative subject. (I have been unable to locate the original source for examples 17–18.)

الاكثر قراءة في Pronouns

الاكثر قراءة في Pronouns

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)