تاريخ الرياضيات

الاعداد و نظريتها

تاريخ التحليل

تار يخ الجبر

الهندسة و التبلوجي

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

العربية

اليونانية

البابلية

الصينية

المايا

المصرية

الهندية

الرياضيات المتقطعة

المنطق

اسس الرياضيات

فلسفة الرياضيات

مواضيع عامة في المنطق

الجبر

الجبر الخطي

الجبر المجرد

الجبر البولياني

مواضيع عامة في الجبر

الضبابية

نظرية المجموعات

نظرية الزمر

نظرية الحلقات والحقول

نظرية الاعداد

نظرية الفئات

حساب المتجهات

المتتاليات-المتسلسلات

المصفوفات و نظريتها

المثلثات

الهندسة

الهندسة المستوية

الهندسة غير المستوية

مواضيع عامة في الهندسة

التفاضل و التكامل

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

معادلات تفاضلية

معادلات تكاملية

مواضيع عامة في المعادلات

التحليل

التحليل العددي

التحليل العقدي

التحليل الدالي

مواضيع عامة في التحليل

التحليل الحقيقي

التبلوجيا

نظرية الالعاب

الاحتمالات و الاحصاء

نظرية التحكم

بحوث العمليات

نظرية الكم

الشفرات

الرياضيات التطبيقية

نظريات ومبرهنات

علماء الرياضيات

500AD

500-1499

1000to1499

1500to1599

1600to1649

1650to1699

1700to1749

1750to1779

1780to1799

1800to1819

1820to1829

1830to1839

1840to1849

1850to1859

1860to1864

1865to1869

1870to1874

1875to1879

1880to1884

1885to1889

1890to1894

1895to1899

1900to1904

1905to1909

1910to1914

1915to1919

1920to1924

1925to1929

1930to1939

1940to the present

علماء الرياضيات

الرياضيات في العلوم الاخرى

بحوث و اطاريح جامعية

هل تعلم

طرائق التدريس

الرياضيات العامة

نظرية البيان

Curves

المؤلف:

Tony Crilly

المصدر:

50 mathematical ideas you really need to know

الجزء والصفحة:

125-131

21-2-2016

3037

It’s easy to draw a curve. Artists do it all the time; architects lay out a sweep of new buildings in the curve of a crescent, or a modern close. A baseball pitcher throws a curveball. Sportspeople make their way up the pitch in a curve, and when they shoot for goal, the ball follows a curve. But, if we were to ask ‘What is a curve?’ the answer is not so easy to frame.

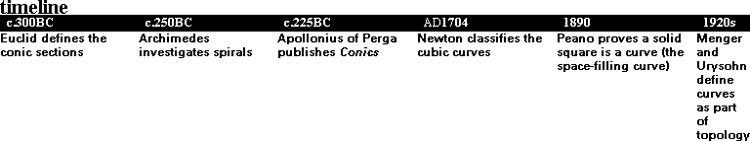

Mathematicians have studied curves for centuries and from many vantage points. It began with the Greeks and the curves they studied are now called the ‘classical’ curves.

The conic sections

Classical curves

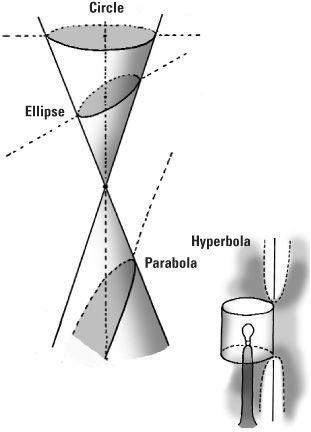

The first family in the realm of the classical curves are what we call ‘conic sections’. Members of this family are the circle, the ellipse, the parabola, and the hyperbola. The conic is formed from the double cone, two ice-cream cones joined together where one is upside down. By slicing through this with a flat plane the curves of intersection will be a circle, an ellipse, a parabola or a hyperbola, depending on the tilt of the slicing plane to the vertical axis of the cone.

We can think of a conic as the projection of a circle onto a screen. The light rays from the bulb in a cylindrical table lamp form a double light cone where the light will throw out projections of the top and bottom circular rims. The image on the ceiling will be a circle but if we tip the lamp, this circle will become an ellipse. On the other hand the image against the wall will give the curve in two parts, the hyperbola.

The conics can also be described from the way points move in the plane. This is the ‘locus’ method loved by the Greeks, and unlike the projective definition it involves length. If a point moves so that its distance from one fixed point is always the same, we get a circle. If a point moves so that the sum of its distances from two fixed points (the foci) is a constant value we get an ellipse (where the two foci are the same, the ellipse becomes a circle). The ellipse was the key to the motion of the planets. In 1609, the German astronomer Johannes Kepler announced that the planets travel around the sun in ellipses, rejecting the old idea of circular orbits.

The parabola

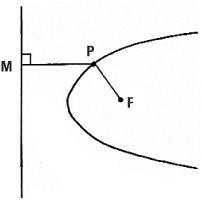

Not so obvious is the point which moves so that its distance from a point (the focus F) is the same as its perpendicular distance from a given line (the directrix). In this case we get a parabola. The parabola has a host of useful properties. If a light source is placed at the focus F, the emitted light rays are all parallel to PM. On the other hand, if TV signals are sent out by a satellite and hit a parabola-shaped receiving dish, they are gathered together at the focus and are fed into the TV set.

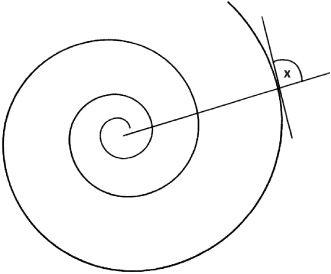

If a stick is rotated about a point any fixed point on the stick traces out a circle, but if a point is allowed to moved outwards along the stick in addition to it being rotated this generates a spiral. Pythagoras loved the spiral and much later Leonardo da Vinci spent ten years of his life studying their different types, while René Descartes wrote a treatise on them. The logarithmic spiral is also called the equiangular spiral because it makes the same angle with a radius and the tangent at the point where the radius meets the spiral.

The logarithmic spiral

Jacob Bernoulli of the famed mathematical clan from Switzerland was so enamoured with the logarithmic spiral that he wanted it carved on his tomb in Basle. The ‘Renaissance man’ Emanuel Swedenborg regarded the spiral as the most perfect of shapes. A three-dimensional spiral which winds itself around a cylinder is called a helix. Two of these – a double helix – form the basic structure of DNA.

There are many classical curves, such as the limaçon, the lemniscate and the various ovals. The cardioid derives its name from being shaped like a heart. The catenary curve was the subject of research in the 18th century and it was identified as the curve formed by a chain hanging between two points. The parabola is the curve seen in a suspension bridge hanging between its two vertical pylons.

Three-bar motion

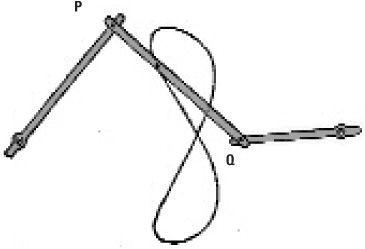

One aspect of 19th-century research on curves was on those curves that were generated by mechanical rods. This type of question was an extension of the problem solved approximately by the Scottish engineer James Watt who designed jointed rods to turn circular motion into linear motion. In the steam age this was a significant step forward.

The simplest of these mechanical gadgets is the three-bar motion, where the bars are jointed together with fixed positions at either end. If the ‘coupler bar’ PQ moves in any which way, the locus of a point on it turns out to be a curve of degree six, a ‘sextic curve’.

Algebraic curves

Following Descartes, who revolutionized geometry with the introduction of x, y and z coordinates and the Cartesian axes named after him, the conics could now be studied as algebraic equations. For example, the circle of radius 1 has the equation x2 + y2 = 1, which is an equation of the second degree, as all conics are. A new branch of geometry grew up called algebraic geometry.

In a major study Isaac Newton classified curves described by algebraic equations of degree three, or cubic curves. Compared with the four basic conics, 78 types were found, grouped into five classes. The explosion of the number of different types continues for quartic curves, with so many different types that the full classification has never been carried out.

The study of curves as algebraic equations is not the whole story. Many curves such as catenarys, cycloids (curves traced out by a point on a revolving wheel) and spirals are not easisly expressible as algebraic equations.

A definition

What mathematicians were after was a definition of a curve itself, not just specific examples. Camille Jordan proposed a theory of curves built on the definition of a curve in terms of variable points.

Here’s an example. If we let x = t2 and y = 2t then, for different values of t, we get many different points that we can write as coordinates (x, y). For example, if t = 0 we get the point (0, 0), t = 1 gives the point (1, 2), and so on. If we plot these points on the x–y axes and ‘join the dots’ we will get a parabola. Jordan refined this idea of points being traced out. For him this was the definition of a curve.

A simple closed Jordan curve

Jordan’s curves can be intricate, even when they are like the circle, in that they are ‘simple’ (do not cross themselves) and ‘closed’ (have no beginning or end). Jordan’s celebrated theorem has meaning. It states that a simple closed curve has an inside and an outside. Its apparent ‘obviousness’ is a deception.

In Italy, Giuseppe Peano caused a sensation when, in 1890, he showed that, according to Jordan’s definition, a filled in square is a curve. He could organize the points on a square so that they could all be ‘traced out’ and at the same time conform to Jordan’s definition. This was called a space-filling curve and blew a hole in Jordan’s definition – clearly a square is not a curve in the conventional sense.

Examples of space-filling curves and other pathological examples caused mathematicians to go back to the drawing board once more and think about the foundations of curve theory. The whole question of developing a better definition of a curve was raised. At the start of the 20th century this task took mathematics into the new field of topology.

the condensed idea

Going round the bend

الاكثر قراءة في هل تعلم

الاكثر قراءة في هل تعلم

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)