Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Rival morphological processes Conversion

المؤلف:

Ingo Plag

المصدر:

Morphological Productivity

الجزء والصفحة:

P219-C7

2025-02-13

988

Rival morphological processes Conversion

We may finally turn to the last of the productive processes, conversion. This process, more specifically denominal conversion, has been the most popular of all verb-deriving processes as a subject of linguistic inquiry. Accounts of the meaning of the zero-affix are extremely numerous and diverse, but all researchers agree that this is an extremely productive process. With regard to structural restrictions on this process, Bauer even states that "if there are constraints on conversion they have yet to be demonstrated" (1983:226).

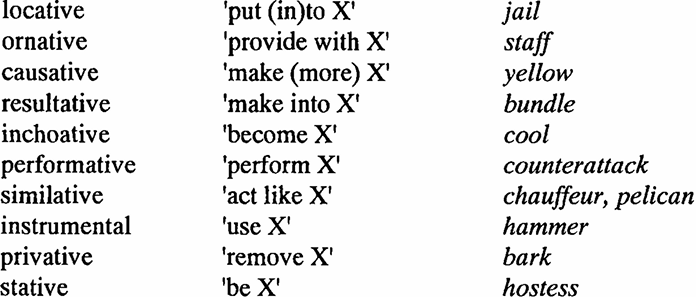

Let us first take a look at the semantics of converted verbs.1 I will not attempt to summarize the existing literature on this topic, but simply list a number of meaning categories (with examples) that have been proposed in the relevant studies (e.g. Kulak 1964, Marchand 1964, 1969, Rose 1973, Karius 1985):

(1)

Sometimes semantic categories have been suggested that cut across the ones proposed above, such as 'movement in time and space' (jet, winter), 'typical action of base' (hammer), 'typical function of base' (cripple), see Karius (1985). The relevance of these labels and their empirical and theoretical justification need not concern us here. What is important, however, is the growing consensus in the linguistic literature that the variety of meanings that can be expressed by zero-affixation is so large that there should be no specific meaning attached to the process of zero-derivation at all.

This position has been argued for in detail in Clark and Clark (1979) and Aronoff (1980) who claim that zero-derivation is a semantically impoverished morphological process.2 Being a verb, the derived form must denote an Event, State, or Process. Being derived from another word, the verb must denote something that has to do with the base word. The diversity of meanings then "follows directly from the fact that the meaning of the verb is limited only to an activity which has some connection with the noun" (Aronoff 1980:747). The correct interpretation of the derived verb crucially involves non-linguistic knowledge (in a way we need not discuss here, see for example Clark and Clark 1979 for some discussion).

Let us turn to the data in the OED. As mentioned earlier, there are about one thousand verbs listed in the OED that are 20th century innovations which are not derived by suffixation. Among these are many back-derived verbs, verbs created by prefixation, parasynthesis, compounding and clipping. Excluding all these verbs plus the ones borrowed from other languages, 488 types remain of the class of verbs I was interested in, i.e. those words that have adopted the syntactic category of verb without any phonological marking on the surface.

These converted verbs can be classified into a number of groups with interesting characteristics. For example, a significant proportion of derivatives have an onomatopoetic motivation (cf. e.g. burp, chuff, clink-clank, oink, ooh, pring, etc.), while others have phrases as their bases (blind-side, cold-call, cold-cream, etc.). A large group of forms are based on nouns, and the smallest group is based on adjectives. Restricting ourselves to nominal and adjectival bases, the neologisms nicely illustrate the semantic indeterminacy of zero-derived verbs. Consider, for example, eel, which can mean 'fish for eel' or 'to move ... like an eel', or premature, which is recorded as having the meaning Of a shell or other projectile: to explode prematurely'. Crew can mean 'act as a (member of a) crew' or 'assign to a crew', young is defined as 'to present the apparently younger side' (paraphrases are cited from the OED). All of the meanings gleaned from the linguistic literature and listed in (22) above are attested in the derivatives in appendix 1: locative archive, ornative marmalade,3 causative rust-proof, resultative package, inchoative gel, performative tango, similative chauffeur, instrumental lorry, privative brash, stative hostess. Instrumental derivatives seem to be the most frequent, which is in line with observations by earlier authors, e.g. Kulak (1964), Karius (1985). In sum, converted verbs can express all those meanings that overtly suffixed verbs can, and many more.

Phonological restrictions seem not to be operative at all, but there are indications of semantic and/or morphological restrictions. For instance, it can be observed that the number of adjectival bases is rather small in comparison the number of nominal bases and onomatopoetic words. Of the 488 verbs, only 17 are derived from adjectives (born, camp, cruel, dual, filthy, hip, lethal, main, multiple, phoney, polychrome, premature, pretty, romantic, rustproof, skinny, young). This is perhaps surprising in view of Gussmann's claim (1987:97) that this process is the most productive one deriving verbs from adjectives. The discrepancy between his claim and my findings probably results from the fact that I have used only neologisms as a database whereas he has included all attested items.4

Gussmann (1987:82) also notes that derived adjectives do not undergo conversion. Although this generalization holds for the majority of our neologisms, it seems that it needs further qualification. Of the converted verbs, at least filthy, partial, polychrome, premature, romantic, rustproof, and skinny are based on homophonous morphologically complex adjectives. A more adequate constraint would perhaps be one which prohibits conversion from relational adjectives. Although no immediate explanation is available why this should be the case, a similar restriction is operative in nominalization, where "abstract suffixes forming quality nouns are only attachable to qualitative (or predicative) adjectives, but not to relational ones" (Rainer 1988:161). These phenomena certainly merit further investigation.

With respect to denominal conversion Marchand (1969:372) reached the conclusion that suffixed and prefixed nouns are impossible bases. Similar facts are reported for Dutch conversion into verbs by Don (1993). Marchand (1969: 372) and Bauer (1983:226) offer blocking as a possible explanation. As we have seen earlier, even if some kind of blocking effect (i.e. token-blocking) can be generally accepted as being responsible for the non-occurrence of certain kinds of formations, blocking does not totally exclude the occasional formation of doublets. Taking this into account, blocking is an uncompelling solution to the problem at hand, because there is an almost complete absence of doublets, which by itself suggests a stronger mechanism. It is unclear at the present stage what this mechanism could be.

Before we finish the discussion of zero-derived verbs let us briefly turn to the theoretical problems involved with zero-derivation. The first of these problems concerns the postulation of zero morphs, the second the input- or output-oriented nature of the rule.

There is a well-known controversy about the question of how to account for the category change of words without formal marking. Essentially two positions are conceivable, one advocating a zero-affix of some sort, the other proposing a category change without any affixation. Most recently, Don (1993) has proposed a third, intermediate alternative, namely the affixation of a morphosemantic AFFIX without any phonological affixation, not even ∅.

The former analysis is usually referred to as zero-derivation or zero-suffixation, the latter two as conversion. In all of the preceding discussion we have used the two terms interchangably without caring about the theoretical implications. It seems however, that the foregoing investigation has a bearing on the question of whether we are dealing with the affixation of a zero-morph or with conversion when we talk about formally unmarked derived verbs in English. I will not review all of the arguments for or against these two approaches, but simply discuss the arguments that emerge from the above examination of verbal derivation. These arguments concern the overt analogue criterion and the question of pre- vs. suffixation of zero, and seem to further undermine the zero-affix hypothesis.

The overt analogue criterion is investigated in detail in Sanders (1988), who formulates it as follows:

THE OVERT ANALOGUE CRITERION (RESTRICTED)

One word can be derived from another word of the same form in a language (only) if there is a precise analogue in the language where the same derivational function is marked in the derived word by an overt (nonzero) form. (Sanders 1988:160-161)

Marchand implicitly uses this criterion to justify the existence of a zero-morph in English verbal derivation, as is illustrated by the following quotation:

If we compare such derivatives as legalize, nationalize, sterilize with vbs [verbs] like clean, dirty, tidy, we note that the syntactic-semantic pattern in both is the same: ... 'make, render clean, dirty, tidy' and 'make, render legal, national, sterile', respectively. ... As a sign is a two facet linguistic entity we say that the derivational morpheme is (phonologically) zero-marked in the case of clean 'make clean'.

(Marchand 1969:359)

Citing some interesting cases of some non-synonymous and some synonymous doublets, Sanders shows that zero and the putatively analogous overt affixes are not in complementary distribution and that zero is only sometimes, but not always in contrast with each of the overt suffixes.5 In other words, zero and the overt suffixes fail to satisfy the overt analogue criterion. How does this relate to the present results?

The systematic investigation of the meaning of derived verbs lends crucial support to Sanders' critical account. While Sanders' examples, though striking, could still be dismissed as isolated cases, the detailed semantic analysis of the individual processes presented above has clearly demonstrated that, while in certain areas their meaning may overlap, there are important and systematic differences between the processes. In the light of these findings, the facts presented by Sanders turn out to be systematic in nature, whereas in other approaches they must be explained away as idiosyncrasies.

The only way to satisfy the overt analogue criterion would be to assume a morphological model in which the semantics is completely separated from the phonological spell-out, such as Beard's lexeme-morpheme base morphology (e.g. 1995). I will postpone a discussion of separation theories until we have looked in more detail at the interaction of the rival processes, which will be done where it is argued that separation is not a viable solution.

The second argument against a zero morph arises from the question whether the putative zero element is prefixed or suffixed. In general, the advocates of the zero morph favor zero-suffixation, a decision that is again based on the overt analogue criterion, since the rival morphs are suffixes. The zero-suffix assumption runs, however, into problems with the prefix eN-, as in enlarge, which may fulfill the same function and would therefore justify another zero-allomorph, a zero-prefix.6 Taking into account the fact that eN- is no longer productive, the whole problem could of course be dismissed on the grounds that the prefixed verbs can be regarded as lexicalizations. Whereas this argument can perhaps solve the problem of eN prefixation, it cannot be used to explain the problem of negative prefixation. In the domain of verb-forming affixation, negative, privative, ablative, and reversative meanings are exclusively expressed by prefixes, such as un-, de- and dis-, while all other possible meanings are expressed by suffixes (and the prefixes eN- and be-).7 The problem now is that the putative zero-suffix can also express negative meanings, thus strongly suggesting the existence of a negative zero-prefix, if we follow the overt analogue criterion. Hence, advocates of the zero-affix would have to posit not only one, but two verb-deriving zero-affixes, one of them a suffix (with a rather general verbal meaning), the other a prefix (with negative, privative, ablative or reversative meaning). It seems that there is even less empirical and theoretical justification for two different verbalizing zero-affixes than there was for one.

The last theoretical problem to be mentioned is the nature of the rules involved. It was already pointed out that many linguists assume the existence of a nominal, and of an adjectival conversion or zero-suffixation rule. The data in appendix 1 indicate however, that, subject to the restrictions discussed above, any kind of sign may undergo conversion into verbs: nouns, adjectives, prepositions, echo words, and phrases.8 Since semantically there is no reason to postulate different rules on the bases of syntactically different input categories, these findings call for an output-oriented rule of conversion.9

1 I use the term 'converted verb' for verbs derived by conversion.

2 See Lieber and Baayen (1993) for a similar account of zero-derived verbs in Dutch.3 There are a number of ornative verbs that are back-derived from adjectives that are in turn derived by the suffixation of ornative -ed to nouns. Where this could be discerned with some certainty (as for example with monoclev < monocled < monocleN) the item was not included in the list of converted verbs.

4 It might also be the case that the productivity of de-adjectival conversion is on the decline in contemporary English, but this question will be left to future research.

5 Consider, for example, Sanders's examples He patroned many fine artists ≠ He patronized many fine artists, I sectioned the article = I sectionized the article.

6 Walinska de Hackbeil (1985) has tried to solve the problem of eN- prefixation by positing a practically meaningless verbal zero-suffix in addition to the locative prefix eN-. Besides the unwarranted postulation of another zero-element (this time not only a zero-morph, but even a zero-morpheme), this anaylsis has the obvious disadvantage that it cannot account for non-locative formations like enlarge.

7 See, for example, Marchand (1973), Colen (1980/81). I am not aware of any convincing explanation for this firm generalization. Note that the morphological expression of negativity in Romance languages is also restricted to prefixes (e.g. Blank 1997). See Lieber and Baayen (1993) for an analysis of similar Dutch verbs.

8 This state of affairs is similar to compounding, where, as convincingly argued by Wiese (1996c), not only phrases may enter compounds (cf. the Charles-and-Di-syndrome), but even non-linguistic signs.

9 The fact that verbs do not seem to undergo conversion is straighforwardly explained. Conversion of verbs into verbs is both phonologically and semantically vacuous. An output-oriented rule of conversion has recently been advocated on the basis of phonological evidence by Kouwenberg (1997) for Papiamento, a Spanish-based Caribbean Creole language.

الاكثر قراءة في Morphology

الاكثر قراءة في Morphology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)