Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Nasals

المؤلف:

Peter Roach

المصدر:

English Phonetics and Phonology A practical course

الجزء والصفحة:

57-6

2024-10-16

1110

Nasals

The basic characteristic of a nasal consonant is that the air escapes through the nose. For this to happen, the soft palate must be lowered; in the case of all the other consonants and vowels of English, the soft palate is raised and air cannot pass through the nose. In nasal consonants, however, air does not pass through the mouth; it is prevented by a complete closure in the mouth at some point. If you produce a long sequence dndndndndn without moving your tongue from the position for alveolar closure, you will feel your soft palate moving up and down. The three types of closure are: bilabial (lips), alveolar (tongue blade against alveolar ridge) and velar (back of tongue against the palate). This set of places produces three nasal consonants - m, n, ŋ - which correspond to the three places of articulation for the pairs of plosives p b, t d, k g.

The consonants m, n are simple and straightforward with distributions quite similar to those of the plosives. There is in fact little to describe. However, N is a different matter. It is a sound that gives considerable problems to foreign learners, and one that is so unusual in its phonological aspect that some people argue that it is not one of the phonemes of English at all. The place of articulation of N is the same as that of k, g; it is a useful exercise to practice making a continuous r) sound. If you do this, it is very important not to produce a k or g at the end - pronounce the N like m or n.

We will now look at some ways in which the distribution of N is unusual.

• In initial position we find m, n occurring freely, but N never occurs in this position. With the possible exception of Ʒ, this makes ŋ the only English consonant that does not occur initially.

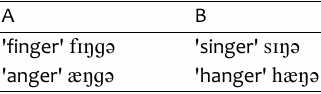

• Medially, ŋ occurs quite frequently, but there is in the BBC accent a rather complex and quite interesting rule concerning the question of when ŋ may be pronounced without a following plosive. When we find the letters 'nk' in the middle of a word in its orthographic form, a k will always be pronounced; however, some words with orthographic 'ng' in the middle will have a pronunciation containing ŋg and others will have ŋ without g. For example, in BBC pronunciation we find the following:

In the words of column A the ŋ is followed by g, while the words of column B have no g. What is the difference between A and B? The important difference is in the way the words are constructed - their morphology. The words of column B can be divided into two grammatical pieces: 'sing' + '-er', 'hang' + ' er'. These pieces are called morphemes, and we say that column B words are morphologically different from column A words, since these cannot be divided into two morphemes. 'Finger' and 'anger' consist of just one morpheme each.

We can summarize the position so far by saying that (within a word containing the letters 'ng' in the spelling) ŋ occurs without a following g if it occurs at the end of a morpheme; if it occurs in the middle of a morpheme it has a following g.

Let us now look at the ends of words ending orthographically with 'ng'. We find that these always end with N; this ŋ is never followed by a g. Thus we find that the words 'sing' and 'hang' are pronounced as sɪŋ and hæŋ; to give a few more examples, 'song' is sɒŋ, 'bang' is bæŋ and 'long' is lɒŋ. We do not need a separate explanation for this: the rule given above, that no g is pronounced after ŋ at the end of a morpheme, works in these cases too, since the end of a word must also be the end of a morpheme. (If this point seems difficult, think of the comparable case of sentences and words: a sound or letter that comes at the end of a sentence must necessarily also come at the end of a word, so that the final k of the sentence 'This is a book' is also the final k of the word 'book'.)

Unfortunately, rules often have exceptions. The main exception to the above morpheme-based rule concerns the comparative and superlative suffixes '-er' and '-est'. According to the rule given above, the adjective 'long' will be pronounced ɪɒŋ, which is correct. It would also predict correctly that if we add another morpheme to 'long', such as the suffix '-ish', the pronunciation of ŋ would again be without a following g. However, it would additionally predict that the comparative and superlative forms 'longer' and 'longest' would be pronounced with no g following the ŋ, while in fact the correct pronunciation of the words is:

'longer' lɒŋgə 'longest' lɒŋgəst

As a result of this, the rule must be modified: it must state that comparative and superlative forms of adjectives are to be treated as single-morpheme words for the purposes of this rule. It is important to remember that English speakers in general (apart from those trained in phonetics) are quite ignorant of this rule, and yet if a foreigner uses the wrong pronunciation (i.e. pronounces ŋg where ŋ should occur, or ŋ where ŋg should be used), they notice that a mispronunciation has occurred.

iii) A third way in which the distribution of ŋ is unusual is the small number of vowels it is found to follow. It rarely occurs after a diphthong or long vowel, so only the short vowels ɪ , e, æ , a, ɒ , ʊ , ə are regularly found preceding this consonant.

The velar nasal consonant N is, in summary, phonetically simple (it is no more difficult to produce than m or n) but phonologically complex (it is, as we have seen, not easy to describe the contexts in which it occurs).

الاكثر قراءة في Phonetics and Phonology

الاكثر قراءة في Phonetics and Phonology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)