Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Clauses

Part of Speech

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Direct and Indirect speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Rhythm

المؤلف:

Peter Roach

المصدر:

English Phonetics and Phonology A practical course

الجزء والصفحة:

117-14

2024-11-01

1871

Rhythm

The notion of rhythm involves some noticeable event happening at regular intervals of time; one can detect the rhythm of a heartbeat, of a flashing light or of a piece of music. It has often been claimed that English speech is rhythmical, and that the rhythm is detectable in the regular occurrence of stressed syllables. Of course, it is not suggested that the timing is as regular as a clock: the regularity of occurrence is only relative. The theory that English has stress-timed rhythm implies that stressed syllables will tend to occur at relatively regular intervals whether they are separated by unstressed syllables or not; this would not be the case in "mechanical speech". An example is given below. In this sentence, the stressed syllables are given numbers: syllables 1 and 2 are not separated by any unstressed syllables, 2 and 3 are separated by one unstressed syllable, 3 and 4 by two, and 4 and 5 by three.

1 2 3 4 5

'Walk 'down the 'path to the 'end of the ca'nal

The stress-timed rhythm theory states that the times from each stressed syllable to the next will tend to be the same, irrespective of the number of intervening unstressed syllables. The theory also claims that while some languages (e.g. Russian, Arabic) have stress-timed rhythm similar to that of English, others (e.g. French, Telugu, Yoruba) have a different rhythmical structure called syllable-timed rhythm; in these languages, all syllables, whether stressed or unstressed, tend to occur at regular time intervals and the time between stressed syllables will be shorter or longer in proportion to the number of unstressed syllables. Some writers have developed theories of English rhythm in which a unit of rhythm, the foot, is used (with a parallel in the metrical analysis of verse). The foot begins with a stressed syllable and includes all following unstressed syllables up to (but not including) the following stressed syllable. The example sentence given above would be divided into feet as follows:

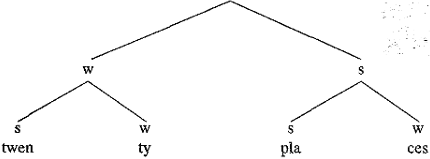

Some theories of rhythm go further than this, and point to the fact that some feet are stronger than others, producing strong-weak patterns in larger pieces of speech above the level of the foot. To understand how this could be done, let's start with a simple example: the word 'twenty' has one strong and one weak syllable, forming one foot. A diagram of its rhythmical structure can be made, where s stands for "strong" and w stands for "weak".

The word 'places' has the same form:

Now consider the phrase 'twenty places', where 'places' normally carries stronger stress than 'twenty' (i.e. is rhythmically stronger). We can make our "tree diagram" grow to look like this:

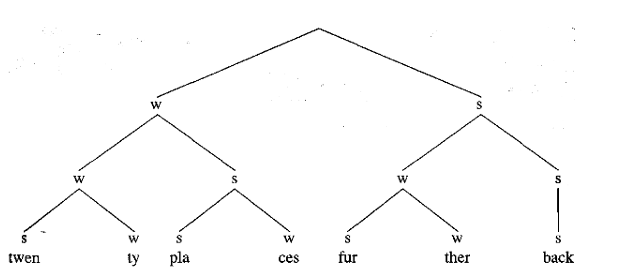

If we then look at this phrase in the context of a longer phrase 'twenty places further back', and build up the 'further back' part in a similar way, we would end up with an even more elaborate structure:

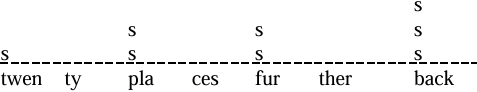

By analyzing speech in this way we are able to show the relationships between strong and weak elements, and the different levels of stress that we find. The strength of any particular syllable can be measured by counting up the number of times an s symbol occurs above it. The levels in the sentence shown above can be diagrammed like this (leaving out syllables that have never received stress at any level):

The above "metrical grid" may be correct for very slow speech, but we must now look at what happens to the rhythm in normal speech: many English speakers would feel that, although in 'twenty places' the right hand foot is the stronger, the word 'twenty' is stronger than 'places' in 'twenty places further back' when spoken in conversational style. It is widely claimed that English speech tends towards a regular alternation between stronger and weaker, and tends to adjust stress levels to bring this about. The effect is particularly noticeable in cases such as the following, which all show the effect of what is called stress shift:

compact (adjective) kəmjpækt but compact disk 'kɒmpækt 'dɪsk

thirteen θз:jti:n but thirteenth place 'θз:ti:nθ' pleɪs

Westminster west'mɪnstə but Westminster Abbey 'westmɪnstər æbi

In brief, it seems that stresses are altered according to context: we need to be able to explain how and why this happens, but this is a difficult question and one for which we have only partial answers.

An additional factor is that in speaking English we vary in how rhythmically we speak: sometimes we speak very rhythmically (this is typical of some styles of public speaking) while at other times we may speak arhythmically (i.e. without rhythm) if we are hesitant or nervous. Stress-timed rhythm is thus perhaps characteristic of one style of speaking, not of English speech as a whole; one always speaks with some degree of rhythmicality, but the degree varies between a minimum value (arhythmical) and a maximum value (completely stress timed rhythm).

It follows from what was stated earlier that in a stress-timed language all the feet are supposed to be of roughly the same duration. Many foreign learners of English are made to practice speaking English with a regular rhythm, often with the teacher beating time or clapping hands on the stressed syllables. It must be pointed out, however, that the evidence for the existence of truly stress-timed rhythm is not strong. There are many laboratory techniques for measuring time in speech, and measurement of the time intervals between stressed syllables in connected English speech has not shown the expected regularity; moreover, using the same measuring techniques on different languages, it has not been possible to show a clear difference between "stress-timed" and "syllable-timed" languages. Experiments have shown that we tend to hear speech as more rhythmical than it actually is, and one suspects that this is what the proponents of the stress-timed rhythm theory have been led to do in their auditory analysis of English rhythm. However, one ought to keep an open mind on the subject, remembering that the large-scale, objective study of suprasegmental aspects of real speech is difficult to carry out, and much research remains to be done.

What, then, is the practical value of the traditional "rhythm exercise" for foreign learners? The argument about rhythm should not make us forget the very important difference in English between strong and weak syllables. Some languages do not have such a noticeable difference (which may, perhaps, explain the subjective impression of "syllable- timing"), and for native speakers of such languages who are learning English it can be helpful to practice repeating strongly rhythmical utterances since this forces the speaker to concentrate on making unstressed syllables weak. Speakers of languages like Japanese, Hungarian and Spanish - which do not have weak syllables to anything like the same extent as English does - may well find such exercises of some value (as long as they are not overdone to the point where learners feel they have to speak English as though they were reciting verse).

الاكثر قراءة في Phonetics and Phonology

الاكثر قراءة في Phonetics and Phonology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)