Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

DYALŊUY CORRESPONDENTS OF SOME VERBS OF MOTION

المؤلف:

R. M. W. DIXON

المصدر:

Semantics AN INTERDISCIPLINARY READER IN PHILOSOPHY, LINGUISTICS AND PSYCHOLOGY

الجزء والصفحة:

443-25

2024-08-19

1204

DYALŊUY CORRESPONDENTS OF SOME VERBS OF MOTION

We must first explain some fragments of the grammar of Dyirbal.

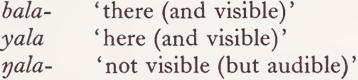

Every head noun in an NP is normally accompanied by a ‘noun marker’; this agrees with the noun in case, indicates which of the four noun classes the noun belongs to, and specifies the visibility/location of the referent of the noun. The first element in a noun marker is one of the three forms:

bala- is also the unmarked form, used when no implication of location/visibility is intended. The second element is a case morpheme: zero for nominative, -ŋgu- for ergative, -gu- for dative, -ŋu- for genitive. Finally there is indication of noun class: -l for class 1, -n class 11, -m class III and zero for class IV (for a full discussion of the noun classes, and their semantic content, see Dixon 1968 b).

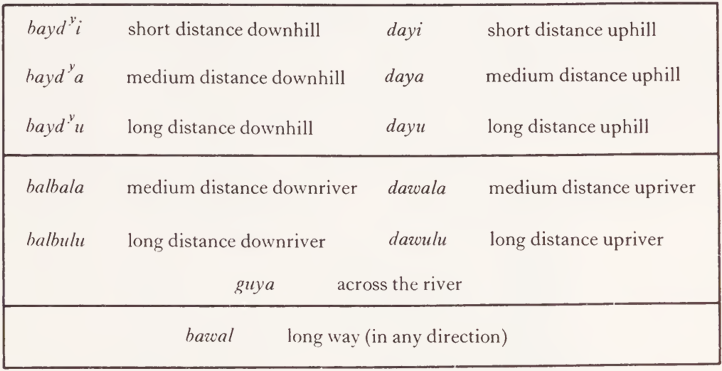

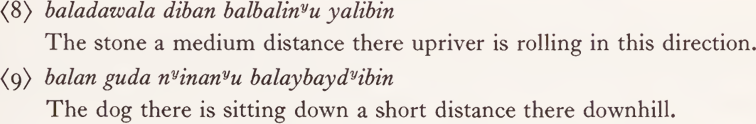

A noun marker can optionally be followed by one of a set of twelve bound forms, further specifying the location of the referent of the noun :1

(Dyirbal is spoken in the Rain Forest just south of Cairns, in the hilly, well- watered area between the east coast and the dividing range; hence the rich set of terms for referring to ‘ up ’, ‘ down ’, with respect to ‘ river ’, ‘ hill ’, etc.)

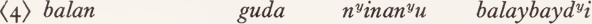

Thus:

there-nom-class n-short distance down hill woman-nom laugh-pres/past The woman a short distance downhill there is laughing.

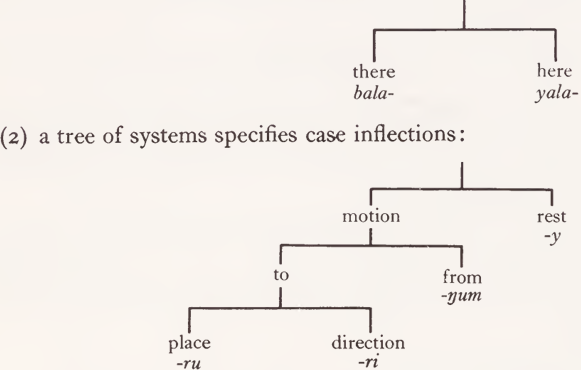

A verb can be accompanied by one of a set of eight verb markers. The first element in a verb marker is one of the forms:

and the second element is a locational case morpheme: -ru ‘to (with respect to a place)’, -ri ‘to (with respect to a direction)’, -ŋum ‘from’, or -y ‘at’. Allative (-ru, -ri) and ablative (-ŋum) forms are usually shortened by the deletion of the -la- of bala- or yala-, the -r- of the allative inflections being simultaneously changed to -l-: thus balu, bali, baŋum but balay. A verb marker may optionally be followed by one of the twelve bound forms in the table above. Thus:

there-nom-class iv-medium distance upriver stone-nom roll-pres/past here¬ to (direction)

The stone a medium distance there upriver is rolling in this direction.

there-nom-class 11-across river woman-nom come-pres/past there-from-long way

The woman on the other side of the river there is coming from a long way out there.

there-nom-class 11 dog-nom sit-pres/past there-at-short distance downhill The dog there is sitting down a short distance there downhill.

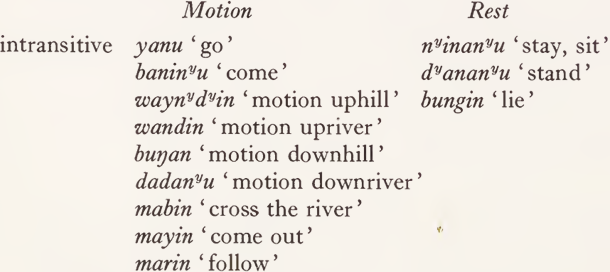

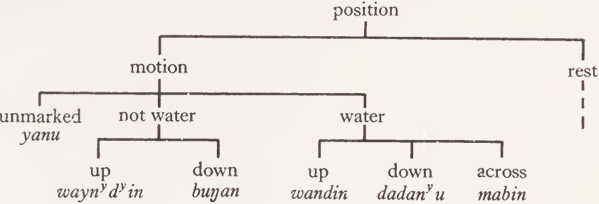

Simple verbs concerned with position fall into two classes: ‘motion’ verbs that occur only with ‘to’ and ‘from’ verb markers, and ‘rest’ verbs that occur only with ‘at’ markers. Typical members of these classes are:

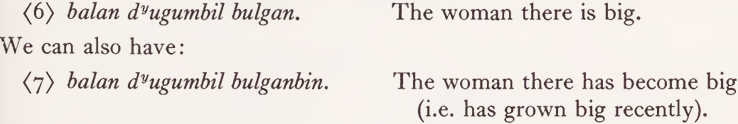

Any noun or adjective stem may be verbalized in three distinct ways: it may be transformed into an intransitive verbal stem by the addition of -bin, or into a transitive verbal stem by the addition of -man (causative) or –(m)ban (non-causative). For instance, bulgan ‘big’ can modify a noun in an NP within an intransitive sentence:

Or we can have a perfectly proper sentence involving just the noun, marker and adjective (there is no verb ‘to be’ in Dyirbal):

The difference between (7) and (6) lies entirely in the active/stative contrast (in the traditional sense) between verbal form bulganbin in (7) and nominal form bulgan in (6). Addition of verbalizer -bin does not affect the semantic content of bulgan, but merely marks it as an intransitive verbal.

Allative (‘to’) and locative (‘at’) verb markers can be verbalized to -bin or ~(m)ban forms (but not to causative -man forms); ablative (‘ from ’) markers cannot be verbalized. Verb markers can be verbalized whether or not they are augmented by bound forms. Thus we can have yalubin, yaluguyabin, balubawalbin and so on; but not *baŋumbin. Thus:

In (2, 4) the verb markers are non-inflecting verbal qualifiers. In (8, 9) the verbalized markers must agree with the head verb in transitivity and tense, and can take the full range of suffixes open to verbs. Speakers of Dyirbal recognize a semantic difference between (2, 4) and (8, 9), but this cannot easily be brought out through English translation.

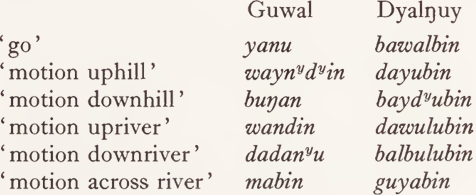

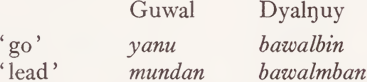

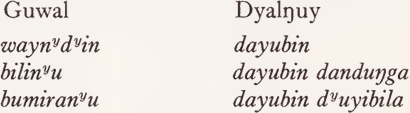

Now Guwal-Dyalŋuy correspondences include the following (the Guwal verbs are all nuclear):

The Dyalŋuy correspondents each consist of a bound form and the intransitive verbalizing affix -bin these bound forms can not by themselves be verbalized in Guwal, although an allative or locative verb marker to which they are bound can.

From our assumption that a one-to-one Guwal-Dyalŋuy correspondence implies a relation of synonymy between the words concerned, and the fact that verbalizer -bin does not change the semantic content of a word, but just marks it as an intransitive verbal, it follows that the semantic content of waynydyin must be the same as that of dayu, and so on. (That is, leaving aside the feature ‘ long way ’ in the semantic description of dayu; verbs of motion do not specify distance and in fact Dyalŋuy correspondents involve the unmarked feature from the system {long, medium, short distance}.)

Verbs markers can be described in terms of semantic features as follows:

(1) a single system specifies ‘here’ or ‘there’ (there is no third ‘heard but not seen ’ feature for verb markers, as there is for noun markers):

-ru and -ri are grouped together as ‘to’ since they (unlike ‘from’ and ‘at’) can cooccur with nouns and adjectives in allative inflection; ‘ to ’ and ‘ from ’ are grouped together, as ‘motion’, since one class of verbs normally occur only with motion markers, and another class normally occur only with rest markers.

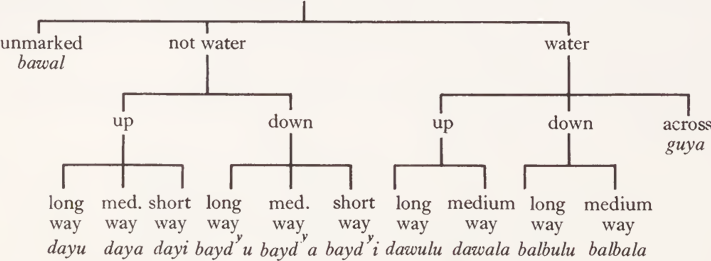

(3) bound forms –baydyi etc. can be described by the tree :2

The fact that simple verbs concerned with position3 fall into two classes, ‘ motion ’ and ‘ rest suggests that the semantic descriptions of these verbs should be taken to include the appropriate feature: ‘motion’ or ‘rest’. From this and the Dyalŋuy data we can generate semantic descriptions:

Verbs of ‘rest’ can be further distinguished through the widely-occurring - if not universal - system {stand, sit, lie}.4

We see that in the semantic descriptions of verb markers, the choice of a feature from the system {water, not water, unmarked} is independent of the choice made from system {motion, rest}. In the case of verbs, however, a feature from the system {water, not water, unmarked} can only be included in a semantic description together with the feature ‘ motion ’, and not with the feature ‘ rest ’. That is, there are verbs specifying ‘whereness ’ of motion but not ‘ whereness ’ of rest; whereas verb markers can specify ‘ whereness ’ of both motion and rest.

Looking now at the Dyalŋuy correspondents of yanu and mundan:

we see that we have the (non-causative) transitive verbalizer -(m)ban, plus bawal, for mundan, as against intransitive verbalizer -bin plus bawal for yanu. This would suggest that yanu and mundan have the same semantic content, and differ only in that mundan belongs to the class of transitive verbs and yanu to that of intransitive verbs.

We have thus been able to provide semantic descriptions of a number of verbs of motion entirely in terms of (1) features from systems which underlie grammatical categories in Dyirbal, and (2) specification of transitivity.

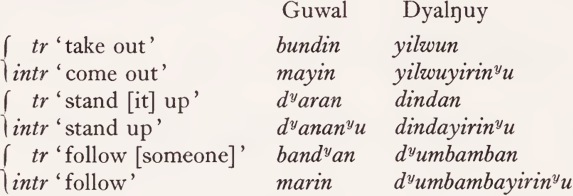

Dyirbal verbs are very strictly categorized as transitive or intransitive; there are a number of pairs of verbs that appear to have the same or almost the same semantic content and to differ only in transitivity, but (with one exception: ŋabanyu ‘ bathe ’; ŋaban ‘ immerse in water ’) the members of such pairs are non-cognate. In almost all these cases there is a single transitive verb in Dyalŋuy; the reflexive form of this verb is given as Dyalŋuy correspondent of the intransitive member of the Guwal pair.5 For instance:

The Dyalŋuy data provides clear evidence that dyananyu and dyaran have the same semantic content, and differ only in transitivity; and similarly in the other cases.

Initially dayubin was given as correspondent not only of waynydyin ‘ motion up, usually uphill ’ but also of bilinyu ‘ climb a tree (without any aid) ’ and of bumiranyu ‘ climb a tree with the help of a length of loya vine (gamin)’.6 At a later stage of elicitation the informant volunteered fuller correspondents:

where dandu corresponds to Guwal yugu ‘ tree, stick ’ and dyuyi to Guwal gamin ‘ loya vine ’. In the case of bilinyu, dayubin is qualified by dandu in locative inflection (i.e. ‘climb [at] a tree’); for bumiranyu, dyuyibila ‘with a gamin' is specified as qualification of the subject of the verb.

Now we could extend the tree on page 447 by including an extra system {X1, X2, X3}:

where X1 refers to climbing a tree with a gamin, X2 to climbing a tree (without a gamin) and X3 is the unmarked feature; in fact, waynydyin can either have a generic meaning, including the particular meanings of bilinyu and bumiranyu, or else a more specific meaning, complementary to those of the other two words (‘ climb something other than a tree, e.g. a hill, steep bank or cliff’). However, X1 X2 and X3 would be entirely ad hoc: these features would not recur in the semantic descriptions of any other words. We would not be providing any semantic insight by setting up a three-feature system merely semantically to distinguish three words. And in fact yugu and gamin are ‘ nuclear ’ nouns, dealt with by the semantic description of the class of nouns; dyuyi and dandu are in normal syntactic relations with dayubin in the Dyalŋuy correspondents. We can thus take waynydyin as a nuclear verb, with semantic description (position, motion, not water, up; intransitive) and bilinyu and bumiranyu as non-nuclear verbs, semantically defined in terms of the semantic descriptions of waynydyin and of two nouns, through established grammatical relations. There is no need to set up the ad hoc system {X1, X2, X3}. (However, we cannot dispense with any of the features in the tree on page 447; waynydyin, mabin, etc. can not be defined in terms of any other words; and in any case these features do occur both in the semantic descriptions of a number of lexical words, and within the grammar.).

1 There is a thirteenth form, ŋaru ‘behind’, in the Mamu/dialect only. There is also a further set of bound forms: gali ‘ vertically down gala ‘ vertically up galu ‘ directly in front ’. A noun or verb marker can optionally be accompanied by one form from the baydyi set and/or one form from the gali set (in that order).

2 We can give phonological realizations for the features in the tree, and thus generate ten of these forms (the exceptions are bawal and guya). ‘ Up ’ is associated with phonological specification daS, ‘ down ’ with baLP, where S, P and L stand for ‘ semivowel ’, ‘ plosive ’ and ‘ link¬ ing consonant (after a vowel and before an intersyllabic nasal and/or plosive)’ respectively. ‘ Not water ’ is associated with a prosody pf palatalization and ‘ water ’ with one of labialization; the prosodies extend over all segments not already fully specified, i.e. over S, P and L in the forms above. -S plus palatalization is the segment y; S plus labialization is w. P plus palatalization is dv; plus labialization is b. The linking consonant can be y, l, r or ɽ; L plus palatalization is y. There is no specifically bilabial linking consonant, so that L plus labialization specifies quite naturally the ‘ unmarked’ linker l. Thus forms day-, daw-, baydy~, balb- are generated. ‘ Short ‘medium ’ and ‘long distance are associated with -i, -a and -u respectively. (For a discussion of the extra affix -lu ~ -la on ‘ water ’ forms, of phonological marking, and of the full phonological structure of Dyirbal, see Dixon 1968 a.)

3 There is no obvious term to refer to both verbs of motion and verbs of rest; ‘ position ’ is used here as something that seems no worse than any other possibility.

4 The semantic description of yanu - but not those of waynydyin, buŋan, wandin, dadanyu and mabin - also involves the unmarked features ‘to’ and ‘there’, contrasting with the semantic description of baninyu ‘ come ’ which involves ‘ to ’ and ‘ here The Dyalŋuy correspondent of baninyu is yalibin, i.e. the verbalized form of the ‘to (direction) here’ marker (and to keep Dyalŋuy different from Guwal, yali - unlike other verb markers bali, yalu, balu, yalay, balay - does not occur in intransitively verbalized form in Guwal).

5 The addition of affix -yiriy ~ -mariy to a transitive stem produces a reflexive form, that functions like an intransitive stem.

6 For a full account (and picture) of the method of tree-climbing with a gamin implement, see Lumholtz 1889, 89-90.

The examples above have shown how Guwal-Dyalŋuy correspondences provide an immediate rationale for the division into nuclear and non-nuclear verbs; and for the techniques of componential description of nuclear words and of definition of non-nuclear words.

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)