Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Clauses

Part of Speech

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Direct and Indirect speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Constituency

المؤلف:

PAUL R. KROEGER

المصدر:

Analyzing Grammar An Introduction

الجزء والصفحة:

P28-C3

2025-12-06

591

Constituency

Examples like (2) show that the words within a phrase or sentence are organized into sub-groups (or CONSTITUENTS), and that these groupings are often crucial in determining what the sentence means. Once we accept that fact a practical question arises, namely how are we to identify these significant sub-groups, since their boundaries are (in general) invisible? In some cases, the answer may seem obvious, even trivial. To see this, try (without looking below) to divide the Malay sentences in (7) into their major constituent parts:

(7) a Ahmad makan nasi.

Ahmad eat rice

‘Ahmad is eating rice.’

b Fauzi makan roti.

Fauzi eat bread

‘Fauzi is eating bread.’

c Orang ini makan ikan.

person this eat fish

‘This person is eating fish.’

d Anjing itu makan tulang besar.

dog that eat bone big

‘That dog is eating a big bone.’

e Orang tua itu makan pisang.

person old that eat banana

‘That old person is eating a banana.’

f Ahmad makan ikan besar itu.

Ahmad eat fish big that

‘Ahmad is eating that big fish.’

Almost certainly, you would make the divisions in the places marked in (8). Why? First, these examples show that a single word (e.g. Ahmad) can be replaced by phrases containing two or three words (anjing itu, orang tua itu, etc.). Since a single word is obviously a “unit” of some kind, the phrases which can be substituted in the same position should also be units of the same kind. Moreover, each of these phrases forms a semantic unit: orang tua itu refers to a single, specific, individual. And, although it contains three words, the phrase bears only one GRAMMATICAL RELATION in sentence (7e), namely subject.

(8) a Ahmad| makan | nasi. ‘Ahmad is eating rice.’

b Fauzi | makan | roti. ‘Fauzi is eating bread.’

c Orang ini | makan | ikan. ‘This person is eating fish.’

d Anjing itu | makan | tulang besar. ‘That dog is eating a big bone.’

e Orang tua itu | makan | pisang. ‘That old person is eating a banana.’

f Ahmad| makan | ikan besar itu. ‘Ahmad is eating that big fish.’

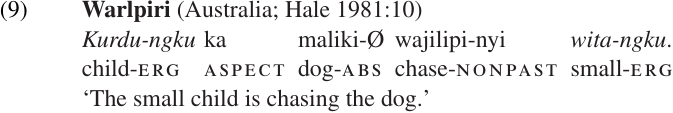

But we must be careful here. In some languages, a group of words which forms a semantic and functional (or relational) unit does not always form a unit for purposes of word order (i.e. a constituent). For example, the subject of the Warlpiri sentence in (9) (‘small child’) consists of two words, a noun and an adjective, which are widely separated from each other and so could not form a constituent in the normal sense.

Such languages are the exception rather than the rule; but in all languages there are many contexts where semantics and Grammatical Relations alone will not enable us to determine the constituent boundaries. We need other kinds of evidence, in particular evidence that is more directly related to the linear arrangement of words in the sentence.

At this point, we can only offer a preliminary introduction to the kinds of tests used to determine the boundaries of syntactic constituents. Identifying constituents can be a complex issue and sometimes requires a fairly deep knowledge of the language. Moreover, tests that work for one language may not apply to another. But let us see how we might proceed with our Malay examples.

One reason for believing that the words orang tua itu in (7e) form a syntactic constituent is that the same string of words can occur in a variety of positions within the sentence: subject (10a), object (10b), object of a preposition (10c), etc. Each of these positions could equally well be filled by a single word, e.g. a proper name like Ahmad.

(10) a [Orang tua itu] makan nasi goreng.

person old that eat rice fry

‘That old person eats fried rice.’

b Saya belum kenal [orang tua itu].

I not.yet know person old that

‘I am not yet acquainted with that old person.’

c Ibu memberi wang kepada [orang tua itu].

mother give money to person old that

‘Mother gives money to that old person.’

d Ibu belanja [orang tua itu] minum teh.

mother treat person old that drink tea

‘Mother bought a cup of tea for that old person.’

We noted above that strings of words which can replace a single word in a particular position must be “units” (i.e. constituents) of the appropriate type. This conclusion is supported by the discovery that only one such unit can occur as the subject or direct object of a single verb, as demonstrated in (11). (The asterisk “*” before the sentences in [11] indicates that they are ungrammatical.) Therefore, where several words occur together in these positions, as in (10a,b), those words must form a single constituent.

(11) a *[Perempuan ini] [orang tua itu] makan nasi.

woman this person old that eat rice

*‘This woman that old person is eating rice.’

b*Fauzi makan [ikan itu] [nasi goreng].

Fauzi eat fish that rice fry

*‘Fauzi is eating fried rice that fish.’1

Malay, like most other languages, has various ways of changing the word order of a sentence. When a group of words can be “moved” as a unit, we can normally assume that the group forms a syntactic constituent. So, examples like (12b–d) support the claim that the direct object phrase in (12a) is a constituent.

(12) a Saya makan [ikan besar itu].

I eat fish big that

‘I ate/am eating that big fish.’

b [Ikan besar itu] saya makan.

fish big that I eat

‘That big fish I ate/am eating.’

c [Ikan besar itu]=lah yang saya makan.

fish big that=FOC REL I eat

‘It was that big fish that I ate.’

d [Ikan besar itu] di-makan oleh anjing saya.

fish big that PASS-eat by dog my

‘That big fish was eaten by my dog.’

Another reason for identifying the phrases we have been discussing here as constituents is that they can be replaced by question words to form a content question (sometimes called a CONSTITUENT QUESTION). This is illustrated in (13).

(13) a [Orang tua itu] makan [ikan besar itu].

person old that eat fish big that

‘That old person ate the big fish.’

b Siapa makan [ikan besar itu]?

who eat fish big that

‘Who ate that big fish?’

c [Orang tua itu] makan apa?

person old that eat what

‘What did that old person eat?’

Similarly, constituent scan form the answer to a content question, whereas a string of words which is not a syntactic constituent is not a possible answer, as illustrated in (14c).

(14) a Q: Siapa makan ikan besar itu? A: Orang tua itu.

who eat fish big that person old that

Q: ‘Who ate that big fish?’ A: ‘That old person.’

b Q: Orang tua itu makan apa? A: Ikan besar itu.

person old that eat what fish big that

Q: ‘What did that old person eat?’ A: ‘That big fish.’

c Q: Orang tua itu makan apa? A:*Besar itu.5

person old that eat what big that

Q: ‘What did that old person eat?’ A: * ‘That big.’

Let us briefly summarize the kinds of evidence we have mentioned. We have claimed that certain strings of Malay words form a syntactic constituent because these strings:

a can replace, or be replaced by, a single word;

b occur in positions within the sentence which must be unique;

c may occur in a number of different sentence positions, as illustrated in (10), and can be “moved” (or re-ordered) as a unit, as illustrated in (12);

d can be replaced by a question word;

e can function as the answer to a content question.

As mentioned above, gathering this kind of evidence often requires a significant amount of knowledge about the grammar of the language. When beginning to study a new language “from scratch,” it is reasonable to make some initial hypotheses about constituent structure based on factors such as meaning and potential for substitution, as we did in our initial discussion of the Malay data. But keep alert for other kinds of evidence which can help you confirm or disprove these hypotheses.

1. The order of the duplicate object NPs is reversed in the English translation to clarify the nature of the ungrammaticality in Malay.

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)