Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

The Dyirbal ‘ mother-in-law language ’ WORD CORRESPONDENCES BETWEEN EVERYDAY AND MOTHER-IN- LAW LANGUAGES

المؤلف:

R. M. W. DIXON

المصدر:

Semantics AN INTERDISCIPLINARY READER IN PHILOSOPHY, LINGUISTICS AND PSYCHOLOGY

الجزء والصفحة:

436-25

2024-08-17

1573

The Dyirbal ‘ mother-in-law language ’

WORD CORRESPONDENCES BETWEEN EVERYDAY AND MOTHER-IN- LAW LANGUAGES

Every user of Dyirbal had at his disposal two distinct languages:

(1) Guwal, the unmarked or ‘everyday’ language; and

(2) Dyalquy, a special (so called ‘mother-in-law’- see Capell 1962, Thomson 1935) language used in the presence of certain ‘taboo’ relatives.

When a man was talking within hearing distance of his mother-in-law, for instance, he had exclusively to use Dyalquy, for talking on any topic; when man and wife were conversing alone they could use only Guwal. The use of one language or the other was entirely determined by whether or not someone in proscribed relation to the speaker was present or near-by; there was never any choice involved.

Dyalquy has identical phonology and almost exactly the same grammar as Guwal.1 However, it has an entirely different vocabulary, there being not a single lexical word common to Dyalquy and Guwal.

Confronted with a Guwal word a speaker will give a unique Dyalquy ‘ equivalent ’. And for any Dyalŋuy word he will give one or more corresponding Guwal words. It thus appears that the two vocabularies are in a one-to-many correspondence: each Dyalŋuy word corresponds to one or more Guwal words (and the words so related are in almost all cases not cognate with each other). For instance, Guwal contains a number of names for types of grubs, including dvambun ‘ long wood grub ’, bugulum ‘small round bark grub’, mandidva ‘milky pine grub’, gidva ‘candlenut tree grub ’, gaban ‘ acacia tree grub ’; there is no Guwal generic term covering all five types of grub. In Dyalŋuy there is a single noun dvamuy ‘grub’ corresponding to the five Guwal nouns; greater specificity can only be achieved in Dyalŋuy by adding a qualifying phrase or clause - describing say the color, habitat or behavior of a particular type of grub - to dvamuy.

The ease with which Guwal-Dyalŋuy correspondences reveal semantic groupings can be seen from the following example.

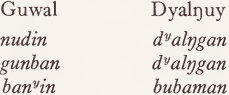

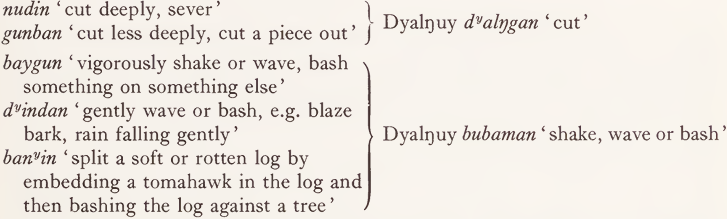

A bilingual informant who offered single word glosses for Guwal verbs identified nudin, gunban and banvin all as ‘ cut ’. But Dyalŋuy correspondents are:

bubaman is also the correspondent of Guwal baygun and dvindan. The meanings of these verbs can be explained as follows:

banvin, which at first appeared to be related to nudin and gunban, is thus seen, on the basis of Dyalŋuy data, to be related to baygun and dvindan, as further specifications of the Dyirbal concept ‘ shake, wave or bash ’; whereas nudin and gunban are further specifications of the quite different concept ‘ cut ’.

Dyalŋuy contains far fewer words than Guwal - something of the order of a quarter as many. Whereas Guwal has considerable hypertrophy, Dyalŋuy is characterized by an extreme parsimony. Every possible syntactic and semantic device is exploited in Dyalŋuy in order to keep its vocabulary to a minimum, it still being possible to say in Dyalŋuy everything that can be said in Guwal. The resulting often rather complex correspondences between Guwal and Dyalŋuy vocabularies are suggestive of the underlying semantic relations and dependencies for the language.

In some cases a Dyalŋuy word corresponds to Guwal items belonging to different word classes. The major word classes in Dyirbal are, on syntactic grounds, noun, whose members refer to objects, spirits, language and noise; adjective, referring to quantities, qualities, states and values of objects; verb, referring to action and perception; adverbal, referring to qualities and values of action and perception; and time qualifiers. Adjectives modify nouns and agree with them in case; in exactly the same way adverbals modify verbs and agree with them in transitivity, and in tense or other final inflection. Now some adjectives refer to qualities of objects that are exactly analogous to qualities of actions, dealt with through adverbals. Dyalŋuy exploits this similarity by having a single word where Guwal has both an adjective and a non-cognate adverbal. Thus Guwal adjective wunay ‘slow’ has Dyalŋuy equivalent wurgal; Guwal intransitive adverbal wundinyu ‘do slowly’ is rendered in Dyalŋuy by the intransitively verbalized form of the adjective wurgal, that is wurgalbin. In other cases a state, described by a Guwal adjective, may be the result of an action, described in Guwal by a verb. Dyalŋuy will exploit this relation of ‘consequence’ (cf. Lyons 1963.73), having either just a verb or just an adjective where Guwal has both verb and adjective. Thus Guwal adjective yagi ‘ broken, split, torn’ has Dyalŋuy correspondent yilgil', Guwal verb ɽulban ‘to split’ is in Dyalŋuy yilgilman, the transitively verbalized form of the adjective yilgil. And Guwal transitive verb nyadyun ‘to cook’ is in Dyalŋuy durman, Guwal adjective nyamu ‘ cooked ’ has Dyalŋuy correspondent durmanmi, the perfective participle of the verb durman. Guwal-Dyalŋuy word correspondences thus reveal the semantic connection between certain quality adjectives and certain quality adverbals; and between certain state adjectives and certain ‘ affect ’ verbs.

1 Grammatical differences are only differences of degree: Dyalŋuy makes much more use of verbalisation and nominalisation processes than does Guwal; and so on.

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)