Semantic markers vs. semantic distinguishers

المؤلف:

URIEL WEINREICH

المؤلف:

URIEL WEINREICH

المصدر:

Semantics AN INTERDISCIPLINARY READER IN PHILOSOPHY, LINGUISTICS AND PSYCHOLOGY

المصدر:

Semantics AN INTERDISCIPLINARY READER IN PHILOSOPHY, LINGUISTICS AND PSYCHOLOGY

الجزء والصفحة:

317-18

الجزء والصفحة:

317-18

2024-08-06

2024-08-06

1622

1622

Semantic markers vs. semantic distinguishers

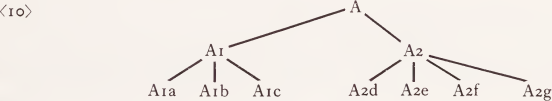

A desire to analyze a global meaning into components, and to establish a hierarchy among the components, has always been one of the major motivations of semantic research. One criterion for hierarchization has been the isolation of designation or connotation (‘ lexical meaning ’, in Hermann Paul’s terms; ‘ distinctive ’, in Bloomfield’s) for study by linguistics, while relegating ‘ mere ’ reference or denotation (‘ occasional ’ meaning, according to Paul) to some other field.1 A further criterion - within the elements of designation - has been used in studies of such areas of vocabulary as can be represented as taxonomies: in a classification such as (10), features introduced at the bottom level (a, b, ... g) differ from the non-terminal features (1, 2; A) in that each occurs only once.

The hierarchization of semantic features into markers and distinguishers in KF does not seem to correspond to either of the conventional criteria, although the discussion is far from clear. Markers are said to ‘reflect whatever systematic relations hold between items and the rest of the vocabulary of the language’, while distinguishers ‘do not enter into theoretical relations’. Now distinguishers cannot correspond to features of denotata, since denotata do not fall within the theory at all. Nor can they correspond to the lowest-level features of a taxonomy, for these - e.g. the features (a, b, ... g) in a vocabulary such as (10) - very definitely do enter into a theoretical relation; though they are unique, they alone distinguish the coordinate species of the genera A1 and A2.

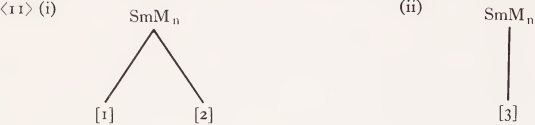

The whole notion of distinguisher appears to stand on precarious ground when one reflects that there is no motivated way for the describer of a language to decide whether a certain sequence of markers should be followed by a distinguisher or not. Such a decision would presuppose a dictionary definition which is guaranteed to be correct; the critical semanticist would then merely sort listed features into markers and a distinguisher. But this, again, begs the question, especially in view of the notoriously anecdotal nature of existing dictionaries (Weinreich 1962, 1964), All suggestions in KF concerning the detailed ‘ geometry ’ of distinguishers are similarly unfounded: the theory offers no grounds, for example, for choosing either (11 i) or (11 ii) as the correct statement of a meaning. (SmMn stands for the last semantic marker in a path; bracketed numbers symbolize distinguishers.)

All KF rules concerning operations on distinguishers (e.g. the ‘ erasure clause ’ for identical distinguishers, p. 198) are equally vacuous.

The theory of distinguishers is further weakened when we are told (KF, n. 16) that ‘certain semantic relations among lexical items may be expressed in terms of interrelations between their distinguishers ’. Although this contradicts the definition just quoted, one may still suppose that an extension of the system would specify some special relations which may be defined on distinguishers. But the conception topples down completely in Katz’s own paper (1964b), where contradictoriness, a relation developed in terms of markers, is found in the sentence Red is green as a result of the distinguishers!2 Here the inconsistency has reached fatal proportions. No ad-hoc reclassification of color differences as markers can save the theory, for any word in a language could be so used as to produce an anomalous sentence.

1 See Weinreich (1963a: 152 ff.) for references, and (1964) for a critique of Webster’s New International Dictionary, 3rd edition, for neglecting this division.

2 ‘There are n-tuples of lexical items which are distinguisher-wise antonymous’ (Katz 1964b: 532).

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة