Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Autonomous and arbitrary syntax

المؤلف:

GEORGE LAKOFF

المصدر:

Semantics AN INTERDISCIPLINARY READER IN PHILOSOPHY, LINGUISTICS AND PSYCHOLOGY

الجزء والصفحة:

267-16

2024-08-05

1352

Autonomous and arbitrary syntax

A field is defined by certain questions. For example,

(i) What are the regularities that govern which linear sequences of words and morphemes of a language are permissible and which sequences are not?

(ii) What are the regularities by which the surface forms of utterances are paired with their meanings?

Early transformational grammar, as initiated by Harris [28], [29] and developed by Chomsky [8], [9], made the assumption that (i) could be answered adequately without also answering (ii), and that the study of syntax was the attempt to answer (i). This assumption defined a field which might well be called ‘ autonomous syntax ’, since it assumed that grammatical regularities could be completely characterized without recourse to meaning. Thus, early transformational grammar was a natural outgrowth of American structural linguistics, since it was concerned with discovering the regularities governing the distribution of surface forms.

However, the main reason for the development of interest in transformational grammar was not merely that it led to the discovery of previously unformulated and unformulable distributional regularities, but primarily that, through the study of distributional regularities, transformational grammar provided insights into the semantic organization of language and into the relationship between surface forms and their meanings. If transformational grammar had not led to such insights - if its underlying syntactic structures had turned out to be totally arbitrary or no more revealing of semantic organization than surface structures - then the field would certainly, and justifiably, have been considered dull. It may seem somewhat paradoxical, or perhaps miraculous, that the most important results to come out of a field that assumed that grammar was independent of meaning should be those that provided insights as to how surface grammatical structure was related to meaning.

Intensive investigation into transformational grammar in the years since 1965 has shown why transformational grammar led to such insights. The reason is that the study of the distribution of words and morphemes is inextricably bound up with the study of meanings and how surface forms are related to their meanings. Since 1965, empirical evidence has turned up which seems to show this conclusively. Consequently, a thorough-going attempt to answer (i) will inevitably result in providing answers to (ii). The intensive study of transformational grammar has led to the abandonment of the autonomous syntax position, and with it, the establishment of a field defined by the claim that (i) cannot be answered in full without simultaneously answering (ii), at least in part. This field has come to be called ‘ generative semantics’.

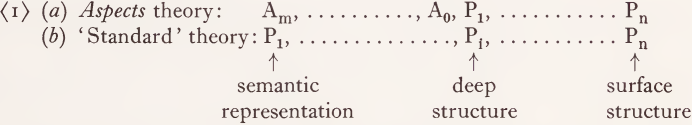

To abandon the autonomous syntax position is to claim that there is a continuum between syntax and semantics. The basic theory has been formulated to enable us to make this notion precise, and to enable us to begin to formulate empirically observed regularities which could not be formulated in a theory of autonomous syntax. Perhaps the empirical issues can be defined more sharply by considering the basic theory vis-a-vis other conceptions of transformational grammar. Suppose one were to restrict the basic theory in the following way. Let PR, TOP, F,... in SR be null. Limit global derivational constraints to those which specify rule order. Limit local derivational constraints to those specifying elementary transformations, as discussed in Aspects. Assume that all lexical insertion transformations apply in a block. The resulting restricted version of the basic theory is what Chomsky in [10] describes as a version of the ‘ standard theory ’.

Of course, not all versions of the theory of grammar that have been assumed by researchers in transformational grammar are restricted versions of the basic theory, nor versions of the standard theory. For example, the theory of grammar outlined in Aspects of the Theory of Syntax [9] is not a version of either the basic theory or the standard theory. The principal place where the theory of Aspects deviates from the standard theory and the basic theory is in its assumption of the inclusion of a non-null Katz-Fodor semantic component, in particular, their conception of semantic readings as being made up of amalgamated paths, which are strings of semantic markers and of symbols which are supposed to suggest Boolean operations.1 They nowhere say that readings are to be defined as phrase-markers made up of the same nonterminal nodes as syntactic phrase-markers, nor do they say that projection rules are operations mapping phrase-markers onto phrase-markers, and I am sure that no one could legitimately read such an interpretation into their discussion of amalgamated paths and Boolean operations on markers. Thus a derivation of a sentence, including the derivation of its semantic reading, would be represented in the Aspects theory as a sequence Am, . . . . . ., A0, P1, . . . . . ., Pn, where the Pi’s are phrase-markers defined as in the basic theory and the standard theory while the Aj’s are amalgamated paths of markers, which are not defined in either the basic theory or the standard theory. (Chomsky [10], p. 188, says: ‘ Suppose further that we regard S as itself a phrase-marker in some “ semantically primitive ” notation.. . . Suppose now that in forming Σ, we construct P1, which is, in fact, the semantic representation S of the sentence.’ In allowing for semantic representations to be phrase-markers, not amalgamated paths, Chomsky is ruling out a nonnull Katz-Fodor semantic component in his new ‘standard theory’.) In the Aspects model it is assumed that the P1’s are defined by well-formedness constraints (base rules). It is not assumed that either the Pn’s (surface structures) or the Am’s (semantic readings) are constrained by any additional well-formedness conditions; rather it is assumed that they are completely characterized by the application of transformations and projection rules to the base structures.

Thus, the Aspects theory differs in an important respect from the basic theory and the standard theory in the definition of a derivation.2

The Aspects theory assumes that semantic readings are formal objects of a very different sort than syntactic phrase-markers and that projection rules are formal operations of a very different sort than grammatical transformations. One of the most important innovations of generative semantics, perhaps the most fundamental one since all the others rest on it, has been the claim that semantic representations and syntactic phrase-markers are formal objects of the same kind, and that there exist no projection rules, but only grammatical transformations. In his discussion of his new ‘standard theory ’, Chomsky has therefore adopted without fanfare one of the most fundamental innovations made by the basic theory.

The ‘standard ’ theory is a considerable innovation over the Aspects theory in this sense, since it represents an implicit rejection of Katzian semantics and since the difference between having amalgamated paths and phrase-markers as semantic representations is crucial for Chomsky’s claim that there exist surface structure interpretation rules. Suppose this were a claim that there are rules that map surface structures onto amalgamated paths containing strings of semantic markers and symbols for Boolean operations. If it were, then such rules would be formal operations which are of an entirely different nature than grammatical transformations. Then such rules could not have those properties of grammatical transformations that depend crucially on the fact that both the input and output of the transformations are phrase-markers. But it has been shown (Lakoff [42]) that, at least in the case of surface interpretation rules for quantifiers and negatives proposed by Partee [55] and JackendofT [33], such interpretation rules must obey Ross’ constraints on movement transformations (Ross [65]). Since Ross’ constraints depend crucially on both the input and output of the rules in question both being phrase-markers (cf. the account of the coordinate structure constraint), it can be demonstrated that, if the outputs of surface interpretation rules are not phrase-markers, then the surface interpretation rule proposals for handling quantifiers and negation are simply incorrect. Thus, although Chomsky doesn’t give any reasons for adopting this innovation of generative semantics, his doing so is consistent with his views concerning the existence of surface structure rules of semantic interpretation.3

The assumption that there exists a level of deep structure, in the sense of either the Aspects or standard theories defines two possible versions of the autonomous syntax position; to my knowledge, these are the only two that have been seriously considered in the context of transformational grammar. We have already seen that there is evidence against (1b). In what follows, I will discuss just a few of the wide range of cases that indicate that both the Aspects and standard-theory versions of the autonomous syntax position are open to very serious doubt.

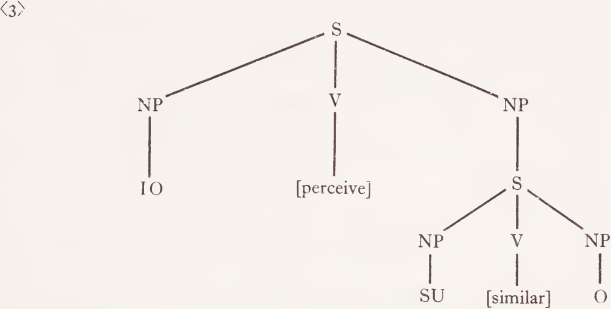

Though Chomsky does not mention the cycle in his discussion of the standard theory, we saw that it interacts crucially with the claim of the standard theory that all lexical insertion rules occur in a block, since it is shown that there can be no level of ‘ deep structure ’ if such is defined as following all lexical insertion rules and preceding all upward-toward-the-surface cyclic rules. The argument also showed that there exist some cases of post-transformational lexical insertion, as was conjectured by McCawley [48] and Gruber [23]. Postal [58] has found a rather remarkable case to confirm McCawley’s conjecture. Postal considers sentences like John strikes we as being like a gorilla with no teeth and John reminds me of a gorilla with no teeth.4 He notes that both sentences involve a perception on my part of a similarity between John and a gorilla with no teeth. This is fairly obvious, since a sentence like John reminds me of a gorilla with no teeth, though I don't perceive any similarity between John and a gorilla with no teeth is contradictory. Postal suggests that an adequate semantic representation for remind in this sense would involve at least two elementary predicates, one of perception and one of similarity. Schematically SU strikes 10 as being like 0 and SU reminds 10 of 0 would have to contain a representation like:

(2) 10 [perceive] (SU [similar] 0)

where [perceive] is a two-place predicate relating 10 and (SU [similar] 0) and [similar] is a two-place predicate relating S and 0.

(2) might be represented as (3):

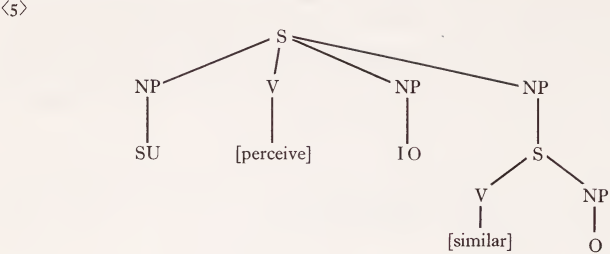

Postal suggests that the semantic representation could be related to the surface structure by the independently needed rules of subject-raising and psych-movement, plus McCawley’s rule of predicate-lifting (McCawley [48]). Subject-raising would produce (4):

Psych-movement would yield (5):

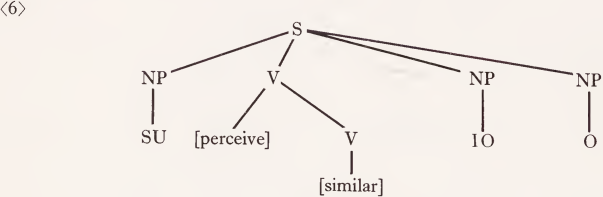

Predicate-lifting would yield (6):

Remind, would substitute for [[PERCEIVE] [SIMILAR] v].5 The question to be asked is whether there is any transformational evidence for such a derivation. In other words, is there any transformational rule which in general would apply only to sentences with a form like (3), which also apply to remind sentences. The existence of such a rule would require that remind sentences be given underlying syntactic structures like (3), which reflect the meaning of such sentences. Otherwise, two such rules would be necessary - one for sentences with structures like (3) and one for remind sentences.

Postal has discovered just such a rule. It is the rule that deletes subjects in sentences like:

(7) To shave oneself is to torture oneself.

(8) Shaving oneself is (like) torturing oneself.

Postal observes that the rule applies freely if the subject is the impersonal one (or the impersonal you). However, there are other, rather restricted circumstances where this rule can apply, namely, when the clause where the deletion takes place is a complement of a verb of saying or thinking and when the NPs to be deleted are coreferential to the subject of that verb of saying or thinking.

The presence of the reflexive indicates what the deleted NP was. Sentences like (11) show that this rule does not apply in relative clauses in addition to complements, and (12) shows that it does not apply if the deleted NPs are identical only to the subject of a verb of saying or thinking more than one sentence up.

(11) *Bill knows a girl who thinks that shaving himself is like torturing himself.

(12) *Mary says that Bill thinks that shaving herself is torturing herself.

Postal notes that this rule also applies in the cases of remind sentences.

If remind is derived from a structure like (3), then this fact follows automatically, since (3) contains a complement and a verb of thinking. If (13) is not derived from a structure like (3), then a separate rule would be needed to account for (13). But that would be only half of the difficulty. Recall that the general rule applies when the NPs to be deleted are subjects of the next highest verb of saying or thinking and the clause in question is a complement of that verb, as in (9) and (10). However, this is not true in the case of remind.

(14) *Mary says that shaving herself reminds Bill of torturing herself.

If remind is analyzed as having an underlying structure like (3), this fact follows automatically from the general rule, since then Mary would not be the subject of the next-highest verb of saying or thinking, but rather the subject of the verb two sentences up, as in (12). Thus, if remind is analyzed as having an underlying syntactic structure like that of (3), one need only state the general rule given above. If remind, on the other hand, is analyzed as having a deep structure like its surface structure, with no complement construction as in (3), then one would (i) have to have an extra rule just for remind (to account for (13)), and (ii) one would have to make remind an exception to the general rule (to account for (14)). Thus, there is a rather strong transformational argument for deriving remind sentences as Postal suggests, which requires lexical insertion to take place following upward-toward-the-surface cyclic rules like subject-raising and psych-movement. This is but one of a consider¬ able number of arguments given for such an analysis by Postal [58].

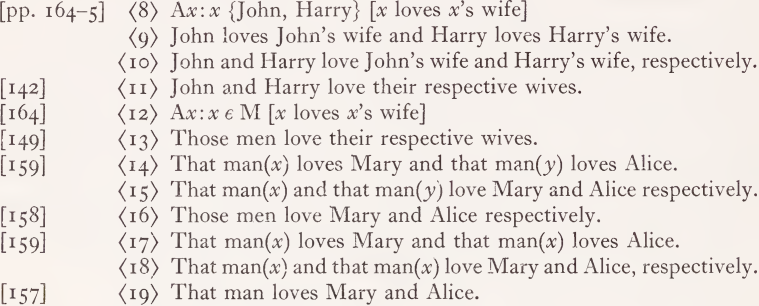

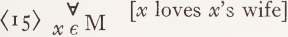

Postal’s claims about remind, if correct, provide crucial evidence of one sort against the existence of a level of deep structure in the sense of both the ‘ standard theory ’ and the Aspects theory, since such a level could be maintained only by giving up linguistically significant generalizations. This would be similar to the argument made by Halle [26] against phonemic representation. Another such argument has been advanced by McCawley [49]. McCawley discusses the phenomenon of respectively-sentences, rejecting the claim that respectively-sentences are derived from sentence conjunction. Chomsky [10] gives a particularly clear description of the position McCawley rejects. Chomsky discusses the following examples. The angle-bracketed numbers correspond to Chomsky’s numbering. The square-bracketed numbers are McCawley’s; where McCawley gives no number, the page is listed. Note that not all the examples have square-bracketed numbers or page references, since Chomsky gives more sentences than McCawley does. (9), (10), (15) and (18) are Chomsky’s examples, not McCawley’s.

Chomsky’s reconstruction of the position McCawley rejects is given in a diagram which he numbers {20):

R' is the rule that converts respectively to respective in the appropriate cases, and C is a rule conjunction collapsing. I, R, and R' are the crucial part of Chomsky’s reconstruction of the argument. I and I' are not mentioned by McCawley at all, and are entirely due to Chomsky. R is what Chomsky refers to as the ‘respectively-transformation ’ as it is discussed in the transformational literature. Such a rule would map (9) into (10) , (14) into (15), and (17) into (18). On pages 163 and 164, McCawley shows that grammars incorporating a rule such as R are inadequate because of their inability to handle sentences containing both plurals and respectively. He then remarks (p. 164):

Thus, in order to explain 141-149, it will be necessary to change the formulation of the respectively transformation so as to make it applicable to cases where there is no conjunction but there are plural noun phrases, or rather, noun phrases with set indices: pluralia tantum do not allow respectively unless they have a set index, so that

156. The scissors are respectively sharp and blunt.

can only be interpreted as a reference to two pairs of scissors and not to a single pair of scissors.

McCawley then goes on to outline what he thinks an adequate rule for stating the correct generalization involved in respectively sentences might look like. (Incidentally, Chomsky describes (20) as the position McCawley accepts rather than the one he rejects. He then proceeds to point out, as did McCawley, that such a position is untenable because of its inadequate handling of plurals. On the basis of this, he claims to have discredited McCawley’s position in particular and generative semantics in general, though in fact he had described neither.)

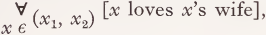

McCawley gives a rather interesting argument. He begins his discussion of what an adequate account of the respectively phenomena might be like as follows (pp. 164-5):

The correct formulation of the respectively transformation must thus involve a set index. That, of course, is natural in view of the fact that the effect of the transformation is to ‘distribute’ a universal quantifier: the sentences involved can all be represented as involving a universal quantifier, and the result of the respectively transformation is something in which a reflex of the set over which the quantifier ranges appears in place of occurrences of the variable which was bound by that quantifier.

He then continues:

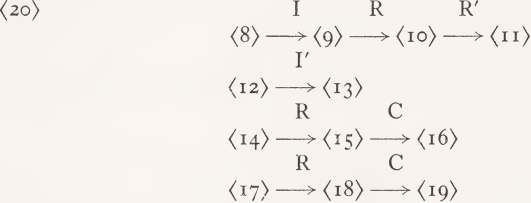

For example, the semantic representation of 149 is something like

where M is the set of men in question, and 142 can be assigned the semantic representation

where x1 corresponds to John and x2 to Harry; the resulting sentence has those men or John and Harry in place of one occurrence of the bound variable, and the corresponding pronominal form they in place of the other occurrence. Moreover, wife takes a plural form, since after the respectively transformation the noun phrase which it heads has for its index the set of all wives corresponding to any x in the set in question. The difference between 142 and 145 is that the function which appears in the formula that the quantifier in 142 binds is one which is part of the speaker’s linguistic competence (f(x) = x’s wife), whereas that in 145 is one created ad hoc for the sentence in question (f(x1) = Mary, f(x2) = Alice).

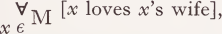

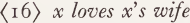

Basically, McCawley is saying the following. The sentences John and Harry love their respective wives and Those men love their respective wives have certain things in common semantically which can be revealed by a common schema for semantic representation, namely,

The differences between the two sentences come in the specification of the set M. In the former case, M is given by the enumeration of its elements, John and Harry, whereas in the latter case, M would be specified by a description of the class (the members each have the properties of being a man). Given that these two sentences have a common form, McCawley notes that ‘the result of the respectively transformation is something in which a reflex of the set over which the quantifier ranges appears in place of the occurrences of the variable which was bound by that quantifier’. Note that he has not proposed a rule; rather he has made the observation that given the open sentence in the above expression

the surface form of the respectively sentences is of essentially this form with the nonanaphoric x’s filled in in the appropriate fashion - by a description (those men) if the set was defined by a description and by a conjunction (John and Harry) if the set was given by enumeration. McCawley does not propose a characterization of the necessary operation. He merely points out that there is a generalization to be stated here, and some such unitary operation is needed to state it.

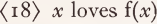

Now McCawley turns to a more interesting case, namely, John and Harry love Mary and Alice respectively. He notes that the form of (15) is not sufficiently general to represent this sentence, and observes that there does exist a more general schema in terms of which this sentence and the other two can be represented.

In cases like (15), f(x) is specified generally in terms of the variable which binds the open sentence, that is, f(x) = x’s wife. In cases like the one mentioned above, the function is specified by an enumeration of its values for each of the members of the set M over which it ranges, that is, f(x1) — Mary and f(x2) = Alice, where M = {x1, x2}. As before, McCawley notes that all three respectively sentences have the surface form of the open sentence

where x and f(x) have been filled in as specified. Again there is a generalization to be captured, and McCawley suggests that in an adequate grammar there should be a unitary operation that would capture it, though he proposes no such operation.

He then makes the following conclusion:

I conclude from these considerations that the class of representations which functions as input to the respectively transformation involves not merely set indices but also quantifiers and thus consists of what one would normally be more inclined to call semantic representations than syntactic representations.

Recall that he is arguing against the Aspects theory, not against the standard theory, and in the following paragraph he goes on to propose what the standard theory but not the Aspects theory assumes, namely, that semantic representations are given in terms of phrase-markers. In the Aspects theory it is assumed that semantic representations and phrase-markers are very different kinds of objects, and McCawley goes on to suggest that if there is a unitary operation relating semantic objects like (17) to the phrase-markers representing respectively sentences and if, as Postal has suggested, ordinary conjunction reduction (which is assumed to map phrase-markers onto phrase-markers) is just a special case of respectively formation (see McCawley [49], pp. 166-7), then respectively formation must be a rule that maps phrase-markers onto phrase-markers, and hence semantic representations like (17) must be given in terms of phrase-markers. If McCawley’s argument goes through, then it would fol¬ low that the concept of deep structure given by the Aspects theory (though not necessarily that of the ‘standard theory’) would be wrong because of its inadequate concept of semantic representation as amalgamated paths. Chomsky’s claim in [10] that McCawley has not proposed anything new in this paper is based on an equivocation in his use of the term ‘deep structure’ and collapses when the equivocation is removed. With respect to the issue of whether or not semantic representations are given by phrase-markers, the notion of ‘deep structure’ in the Aspects theory is drastically different than the notion of ‘deep structure’ in the ‘standard theory ’; thus it should be clear that McCawley’s argument, if correct, would indeed provide a Halle-type argument against the Aspects notion of ‘deep structure’, as was McCawley’s intent.

But McCawley’s proposal is interesting from another point of view as well, for he has claimed that the requirement that one must state fully general rules for relating semantic representations to surface structures may have an effect on the choice of adequate semantic representations. In particular, he claims that an adequate semantic representation for respectively sentences must have a form essentially equivalent to (17). Such a claim is open to legitimate discussion, and whether it turns out ultimately to be right or wrong, it raises an issue which is important not only for linguistics but for other fields as well. Take, for example, the field of logic. Logic, before Frege, was the study of the forms of valid arguments as they occurred in natural language. In the twentieth century, logic has for the most part become the study of formal deductive systems with only tenuous links to natural language, although there is a recent trend which shows a return to the traditional concerns of logic.6 In such logical systems, even the latter sort, the only constraints on what the logical form of a given sentence can be are given by the role of that sentence in valid arguments. From the generative semantic point of view, the semantic representation of a sentence is a representation of its inherent logical form, as determined not only by the requirements of logic, but also by purely linguistic considerations, for example the requirement that linguistically significant generalizations be stated. Thus, it seems to me that generative semantics provides an empirical check on various proposals concerning logical form, and can be said in this sense to define a branch of logic which might appropriately be called ‘ natural logic ’.

The imposition of linguistic constraints on the study of logical form has some very interesting consequences. For example, McCawley (in a public lecture at M.I.T., spring 1968) made the following observations: Performative sentences can be conjoined but not disjoined.

(19) (a) I order you to leave and I promise to give you ten dollars.

(b) *1 order you to leave or I promise to give you ten dollars.

This is also true of performative utterances without overt performative verbs.

(20) (a) To hell with Lyndon Johnson and to hell with Richard Nixon.

(b) *To hell with Lyndon Johnson or to hell with Richard Nixon.

The same is true when conjunction reduction has applied.

(21) (a) To hell with Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon.

(b) *To hell with Lyndon Johnson or Richard Nixon.

McCawley then observes that universal quantifiers pattern in these cases like conjunctions and existential quantifiers like disjunctions.

(22) (a) To hell with everyone.

(b) *To hell with someone.

Ross (personal communication) has pointed out that the same is true of vocatives:

(23) (a) John and Bill, the pizza has arrived.

(b) *John or Bill, the pizza has arrived.

(24) (a) (Hey) everybody, the pizza has arrived.

(b) *(Hey) somebody, the pizza has arrived.

McCawley points out that it is no accident that existential quantifiers rather than universal quantifiers pattern like disjunctions,7 given their meanings. McCawley argues that if general rules governing the syntactic phenomena of (19)-(24) are to be stated, then one must develop, for the sake of stating rules of grammar in general form, a system of representation which treats universal quantifiers and conjunctions as a single unified phenomenon, and correspondingly for existential quantifiers and disjunctions.

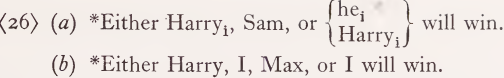

Further evidence for this has been pointed out by Paul Postal (personal communication). It is well known that repeated coreferential noun phrases are excluded in conjunctions and disjunctions. Thus, (25) and (26) are ill-formed:

Postal notes that conjunctions with everyone and disjunctions with someone act the same way:

(27) *Everyone and Sam left.

(28) *Someone or Sam left.8

(27) and (28) are excluded if Sam is assumed to be a member of the set over which everyone and someone range, though of course not, if other assumptions are made. Postal points out that this is the same phenomenon as occurs in (25) and (26), namely, conjuncts and disjuncts may not be repeated. If there is to be a single general rule covering all of these cases, then the rule must be stated in some notation which treats quantifiers and conjunctions as a single unified phenomenon.

A further argument along these lines has been provided by Robin Lakoff (personal communication). It has long been known that in comparative constructions a conjunction may be expressed by a disjunction. Thus the meaning of (29) may be expressed by (30):

(29) Sam likes lox more than herring and whitefish.

(30) Sam likes lox more than herring or whitefish.

(Of course, (30) also has a normal disjunctive reading.) Let us assume that there is a transformation changing and to or in such comparative constructions. Lakoff notes that the same phenomenon occurs with quantifiers:

(31) Sam likes canned sardines more than everything his wife cooks.

(32) Sam likes canned sardines more than anything his wife cooks.

The meaning of (31) can be expressed by (32), in which any replaces every. Again, as she argues, we have the same phenomenon in both cases, and there should be a single general rule to cover both. Thus, the same transformation that maps and into or must also map every into some/any. This can only be done if there is a single unified notation for representing quantifiers and conjunctions.

These facts also provide evidence of the sort brought up by Postal in his discussion of remind (see McCawley [49]), evidence that indicates that certain transformations must precede the insertion of certain lexical items. Consider prefer, which means like more than:

(33) (a) Sam likes lox more than herring.

(b) Sam prefers lox to herring.

As we saw in (29)-(32) above, and optionally changes to or and every to any in the than-clause of comparative constructions. The same thing happens in the corresponding place in prefer constructions, namely, in the to-phrase following prefer.

(34) Sam prefers lox to herring and whitefish.

(35) Sam prefers lox to herring or whitefish.

(36) Sam prefers canned sardines to everything his wife cooks.

(37) Sam prefers canned sardines to anything his wife cooks.

If prefer is inserted for like-more after the application of the transformation mapping conjunctions into disjunctions, then the fact that this mapping takes place in the to-phrase following prefer follows as an automatic consequence of the meaning of ‘prefer ’. Otherwise, this phenomenon must be treated in an ad hoc fashion, which would be to make the claim that these facts are unrelated to what happens in comparative constructions.

Further evidence for such a derivation of prefer comes from facts concerning the ‘stranding’ of prepositions. The preposition to may, in the general case, be either ‘stranded’ or moved along when the object of the preposition is questioned or relativized.

(38) (a) Who did John give the book to.

(b) To whom did John give the bool

(39) (a) Who is Max similar to?

(b) To whom is Max similar?

(40) (a) What city did you travel to?

(b) To what city did you travel?

The preposition than, on the other hand, must be stranded, and may move along only in certain archaic-sounding constructions like (43).

(41) (a) What does Sam like bagels more than?

(b) *Than what does Sam like bagels more?

(42) (a) Who is Sam taller than?

(b) *Than whom is Sam taller?

(43) ? God is that than which nothing is greater.

The preposition to following prefer does not work like ordinary occurrences of to, but instead works just like than; it must be stranded where than is stranded and may move along in just those archaic-sounding constructions where than may.

(44) (a) What does Sam prefer bagels to?

(b) *To what does Sam prefer bagels?

(45) ? God is that to which I prefer only bagels.

Unless prefer is derived from like-more, these facts cannot be handled in a unified way, and the correlation must be considered accidental. Such facts seem to provide even more evidence against the Aspects conception of deep structure.

Let me conclude with one more example. A rather extraordinary case of a syntactic phenomenon whose environment cannot be given in terms of superficial syntactic structure has been reported on by Labov9 as occurring in the speech of Harlem residents.10 The rule involves subject-auxiliary inversion, which moves the first word of the auxiliary to the left of the subject in direct questions (Where has he gone?), after negatives (Never have I seen such a tall boy?), and in certain other environments. However, in the dialect discussed by Labov, this rule operates not simply in direct questions, but in all requests for information, whatever their sur¬ face syntactic structure. The following facts obtain in this dialect.

(46) (a) *Tell me where he went.

(b) Tell me where did he go.

(47) (a) *1 want to know where he went.

(b) I want to know where did he go.

If there is no request for information, inversion does not occur, even with the same verbs.

(48) (a) Bill told me where he went.

(b) *Bill told me where did he go.

(49) (a) I know where he went.

(b) *I know where did he go.

This phenomenon, though it does not occur in standard English, does have its counterpart there in cases like:

(50) Where did he go, I want to know.

(51) *Where did he go, I know.

(52) Where did he go, tell me.

(53) *Where did he go, tell Harry.

In this dialect, even such a late syntactic rule as subject-auxiliary-inversion must be stated not in terms of superficial syntactic structure but in terms of the meaning of the sentence; that is, if the generalization is to be captured the subject-auxiliary inversion rule must have in its structural index the information that the sentence in question describes or is a request for information. This is obviously impossible to state in either the Aspects or ‘standard’ theories.

Given the rather considerable array of evidence against the existence of a level of ‘deep structure’ following all lexical insertion and preceding all upward-toward-the-surface cyclic rules, it is rather remarkable that virtually no arguments have ever been given for the existence of such a level. The arguments that one finds in works of the Aspects vintage will usually cite pairs of sentences like ‘John ordered Harry to leave’ and ‘John expected Harry to leave’, show that they have very different properties, and claim that such properties can be accounted for by assuming some ‘higher’ level of representation reflecting the different meanings of the sentences (‘order’ is a three-place predicate; ‘ expect ’ is a two-place predicate). Such arguments do seem to show that a ‘higher’ or ‘ more abstract ’ level of representation than surface structure exists, but they do not show that this level is distinct from the level of semantic representation. In particular, such arguments do not show that any intermediate level of ‘ deep structure ’ as defined in the precise sense given above exists. It was simply assumed in Aspects that this ‘ higher ’ level contained all lexical items and preceded all transformations; no arguments were given.11

The only attempt to provide such an argument that I have been able to find is a rather recent one. Chomsky [10] cites the context

(54) Bill realized that the bank robber was —

and considers the sentences formed by inserting

(55) John’s uncle

and

(56) the person who is the brother of John’s mother or father or the husband of the sister of John’s mother or father

into the blank in (54). He claims that these sentences would have different semantic representations, and this claim is based on the further claim that ‘what one believes, realizes, etc., depends not only on the proposition expressed, but also on some aspects of the form in which it is expressed ’. These claims are not obviously true, and have been disputed.12 But let us assume for the sake of argument that Chomsky is right in this matter. Chomsky does not propose any account of semantic representation to account for such facts. He does, however, suggest (albeit with reservations and without argument) that such examples refute any theory of grammar without a level of ‘deep structure ’, but not a theory with such a level. He continues:

Do considerations of this sort refute the standard theory as well? The example just cited is insufficient to refute the standard theory, since [)54)—(56)] differ in deep structure, and it is at least conceivable that‘ realize ’ and similar items can be defined so as to take account of this difference (p. 198).

But this is a non sequitur, even given Chomsky’s assumptions. (54)—(56) would show, under Chomsky’s assumptions, only that truth values of sentences depend in part on the particular phonological form in which semantic information is expressed. It does not follow that the correlation between phonological forms and the corresponding semantic information must be made at a single level of grammar, and certainly not at a level preceding all cyclic rules. It only follows that such correlations must be made at some point or other in the derivations defined by a grammar. So long as such correlations are made somewhere in the grammar, ‘it is at least conceivable that “realize” and similar items can be defined so as to take account of’ (54) —(56). Of course, this is not saying much, since anything that pretends to be a grammar must at the very least show how semantic information correlates with phonological form. All that Chomsky’s argument shows is that his examples do not refute any theory of grammar that defines the correlations between semantic information and phonological form, that is, any theory of grammar at all.

This is, as far as I know, the present state of the evidence in favor of the existence of a level of ‘deep structure’ which contains all lexical items and precedes all cyclic rules. Since the burden of proof must fall on someone who proposes a level of ‘deep structure ’, there is at present no good reason to believe in the existence of such a level and a number of good reasons not to. This of course does not mean that there is no intermediate level at all between semantic representations and surface structures. In fact, as we have seen, it is not unreasonable to believe that there exists a level of ‘shallow structure ’, perhaps following all cyclic rules. I think it is fair to say that at present there is a reasonable amount of evidence disconfirming the autonomous syntax position and none positively confirming it. This is, of course, not strange, since virtually no effort has gone into trying to prove that the autonomous syntax position is correct.

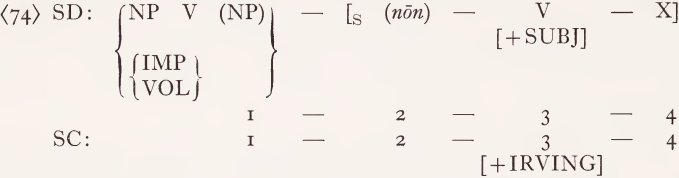

Going hand-in-hand with the position of autonomous syntax is what we might call the position of ‘ arbitrary syntax ’. We might define the arbitrary syntax position as follows: Suppose there is in a language a construction which bears a meaning which is not given simply by the meanings of the lexical items in the sentence (e.g., the English question, or the imperative). The question arises as to what the underlying structure of a sentence with such a ‘ constructional meaning ’ should be. Since the meaning of the construction must appear in its semantic representation (P1, in the standard theory) and since this meaning is represented in terms of a phrase-marker (at least in the standard theory), one natural proposal might be that the ‘ deep structure ’ phrase-marker of the sentence contains the semantic representation corresponding to the construction directly. Call this the ‘ natural syntax ’ position. The arbitrary syntax position is the antithesis of this. It states that the deep structure corresponding to a construction of the sort described never contains the phrase-structure configuration of the meaning of the sentence directly. Instead, the deep structure corresponding to the configuration must contain some arbitrary marker. Consider the English imperative as an example. The meaning of the imperative construction in a sentence like Come here must be given in terms of a three-place predicate relating the speaker, the addressee, and a sentence describing the action to be performed, as expressed overtly in the sentence 1 order you to come here. Any adequate theory of semantic representation must say at least this much about the meaning of Come here. The arbitrary syntax position would maintain in this case that the ‘ deep structure ’ of Come here would not contain such a three-place predicate, but would instead contain an arbitrary marker. In recent studies such a marker has been given the mnemonic IMP, which may tend to hide its arbitrariness. A good name to reveal its true arbitrary nature would be IRVING. Under the arbitrary syntax position, the deep structure of Come here would contain IRVING.13

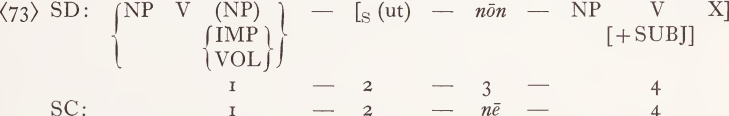

It is possible to show in certain instances that the arbitrary syntax position is incorrect. One of the most telling arguments to this effect has been given by Robin Lakoff in Abstract Syntax and Latin Complementation [44].

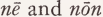

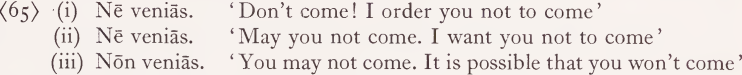

The Lakoff argument concerns the distribution of the Latin subjunctive and of two morphemes indicating sentence negation. She begins by considering the Latin sentence

(57) Venias. (Form: 2nd person singular subjunctive of venio, ‘to come’)

(57) is an example of what is called an ‘ independent subjunctive ’ in Latin* and it is at least three ways ambiguous, as shown in (58):

(58) (i) Come! I order you to come.

(ii) May you come! I want you to come.

(iii) You may come. It is possible that you will come.

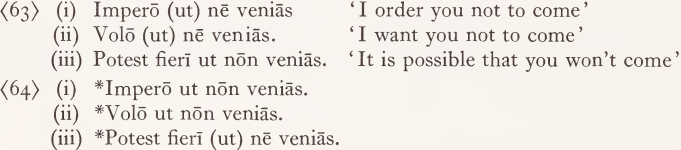

There is also in Latin a dependent subjunctive which functions as a complementizer with verbs of certain meaning classes. Some typical examples are:

(59) (i) Impero ut venias. ‘I order you to come’

(ii) Volo ut venias. ‘ I want you to come ’

(iii) Potest fieri ut venias. ‘It is possible that you will come’.

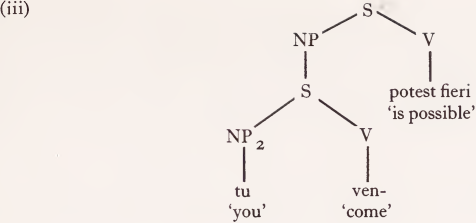

She argues that the sentences of (59) should have underlying structures roughly like (60):

The rule of complementizer-placement will in each case mark the main verb inside a complement structure, that is, one of the form

as subjunctive, given the meaning-class of the next-highest verb.

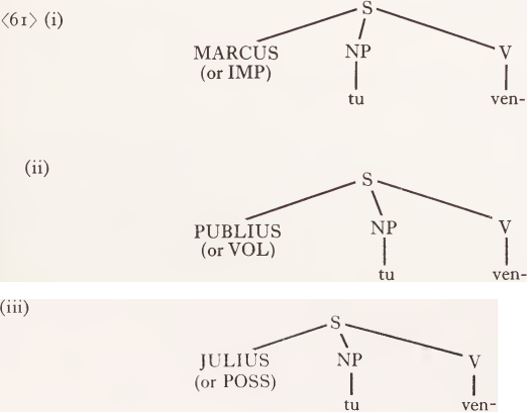

Lakoff then suggests that it might not be an accident that the sentence of (57), which is odd in that it has a subjunctive in the main clause, has the same range of meanings as the sentences of (59), where the normal rule of subjunctive complementation for verbs of those meanings has applied. She proposes that if it were hypothesized that (57) had three underlying structures just like those in (6o), except that in the place of the real predicates impero, volo, and potest fieri there were ‘abstract predicates’, or nonlexical predicates bearing the corresponding meanings, then the subjunctive in (57) would be derived by the same, independently motivated rule that derives the embedded subjunctives of {59). Since the structures of (60) reflect the meanings of the three senses of (57), such a solution would provide an explanation of why a subjunctive should show up in a main clause with just those meanings. But the arbitrary syntax position would rule out such an explanation. In terms of the arbitrary syntax position, (57) would have three different deep structures, all of them with venio as the main verb and with no complement constructions. The difference between the three deep structures could only be given by arbitrary symbols, for example, MARCUS, PUBLIUS, and JULIUS (they might be given mnemonics like IMP, VOL, and POSS, though such would be formally equivalent to three arbitrary names). In such a theory, the three deep structures for (57) would be:

There would then have to be a rule stating that verbs become subjunctive in the environment

Such a rule would be entirely different than the rule that accounts for the subjunctives in (59), and having two such different rules is to make the claim that the appearance of the subjunctive in (57) is entirely unrelated to the appearance of the subjunctive in (59), and that the fact that the same endings show up is a fortuitous accident. To claim that it is not a fortuitous accident is to claim that the arbitrary syntax position is wrong in this respect.14

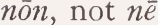

Lakoff then goes on to discuss negatives. In Latin, sentence negation may be expressed by one of two morphemes,  . These are, of course, in complementary distribution, and she shows that in sentential complements there is a completely general rule governing their distribution:

. These are, of course, in complementary distribution, and she shows that in sentential complements there is a completely general rule governing their distribution:  occurs in object complements where the verb inside the complement is subjunctive;

occurs in object complements where the verb inside the complement is subjunctive;  occurs elsewhere, e.g., in nonsubjunctive complements and in subject complements where the main verb is subjunctive. For example, the negatives corresponding to (59) would be (63); the sentences of (64) would be ungrammatical in Latin. Ut is optional before

occurs elsewhere, e.g., in nonsubjunctive complements and in subject complements where the main verb is subjunctive. For example, the negatives corresponding to (59) would be (63); the sentences of (64) would be ungrammatical in Latin. Ut is optional before

In main clauses without subjunctive main verbs we find  , just as in the corresponding complement clauses. But in main clauses with subjunctive main verbs, namely, cases like (57), referred to as ‘independent subjunctives’, we find both

, just as in the corresponding complement clauses. But in main clauses with subjunctive main verbs, namely, cases like (57), referred to as ‘independent subjunctives’, we find both  . That is, both

. That is, both  are grammatical in Latin. However, they do not mean the same thing. Their meanings are distributed as in (65) :

are grammatical in Latin. However, they do not mean the same thing. Their meanings are distributed as in (65) :

The distribution of meanings and negatives in (65) corresponds exactly to the distribution in (63). Lakoff argues that this too is no accident. She notes that if the underlying structures for (57) are those of (60), with the appropriate abstract predicates, then the distribution of negatives in (65) follows the ordinary rules specifying the occurrence of  in object complements, not subject complements. This would explain the facts of (65). However, if the deep structures of (57) are those of (61), then an entirely different rule would have to be stated, namely: in main clauses with subjunctive main verbs the negative appears as

in object complements, not subject complements. This would explain the facts of (65). However, if the deep structures of (57) are those of (61), then an entirely different rule would have to be stated, namely: in main clauses with subjunctive main verbs the negative appears as  if either MARCUS (or IMP) or PUBLIUS (or VOL) is present, and

if either MARCUS (or IMP) or PUBLIUS (or VOL) is present, and  otherwise. Such a rule would be entirely different from the rule for negatives inside complements, and to have two such different rules is to make the claim that there is no generalization governing the distribution of negatives in (65) and (63), and that the fact that the distribution of forms correlates with the distribution of meanings in these cases is a fortuitous accident. To say that it is not an accident is to say that any theory which rules out abstract predicates and forces such rules to be stated instead in terms of arbitrary markers like MARCUS, IRVING, Q, and IMP is wrong, since linguistically significant generalizations cannot be stated in such a theory.

otherwise. Such a rule would be entirely different from the rule for negatives inside complements, and to have two such different rules is to make the claim that there is no generalization governing the distribution of negatives in (65) and (63), and that the fact that the distribution of forms correlates with the distribution of meanings in these cases is a fortuitous accident. To say that it is not an accident is to say that any theory which rules out abstract predicates and forces such rules to be stated instead in terms of arbitrary markers like MARCUS, IRVING, Q, and IMP is wrong, since linguistically significant generalizations cannot be stated in such a theory.

Now consider what the semantic representations of the three senses of (57) would look like. Sense (i), which is an order, would involve a three-place predicate, specifying the person doing the ordering, the person to whom the order is directed, and the proposition representing the order to be carried out. If one conceives of semantic representation as being given along the lines suggested in Lakoff [43] such a semantic representation would look essentially like (60 i). Similarly, sense (ii) of (57) expresses a desire, and so its semantic representation would have to contain a two-place predicate indicating the person doing the desiring and the proposition expressing the content of the desire. That is, it would essentially have the structure of (60ii). Sense (iii) of (57) expresses a possibility, and so would have in its semantic representation a one-place predicate containing a proposition, as in (60iii). In short, if semantic representations are given as in Lakoff [43], then the semantic structures are exactly the structures required for the formulation of general rules introducing the subjunctive complementizer and  in Latin. This seems to me to support the claim that semantic representations are given in terms of syntactic phrase-markers, rather than, say, the amalgamated paths of the Aspects theory. It also seems to support the generative semantics position that there is no clear distinction between syntactic phenomena and semantic phenomena. One might, of course, claim that the terms ‘syntactic phenomena’ and ‘semantic phenomena ’ are sufficiently vague as to render such a statement meaningless. But I think that there are enough clear cases of ‘syntactic phenomena’ to give the claim substance. It seems to me that if anything falls under the purview of a field called ‘syntax’ the rules determining the distribution of grammatical morphemes do. To claim that such rules are not ‘syntactic phenomena ’ seems to me to remove all content from term ‘ syntax Thus the general rules determining the distribution of the two negative morphemes

in Latin. This seems to me to support the claim that semantic representations are given in terms of syntactic phrase-markers, rather than, say, the amalgamated paths of the Aspects theory. It also seems to support the generative semantics position that there is no clear distinction between syntactic phenomena and semantic phenomena. One might, of course, claim that the terms ‘syntactic phenomena’ and ‘semantic phenomena ’ are sufficiently vague as to render such a statement meaningless. But I think that there are enough clear cases of ‘syntactic phenomena’ to give the claim substance. It seems to me that if anything falls under the purview of a field called ‘syntax’ the rules determining the distribution of grammatical morphemes do. To claim that such rules are not ‘syntactic phenomena ’ seems to me to remove all content from term ‘ syntax Thus the general rules determining the distribution of the two negative morphemes  in Latin and the subjunctive morpheme in Latin should be ‘syntactic, phenomena’ if there are any ‘ syntactic phenomena ’ at all. Yet as we have seen, the general rules for stating such distributions must be given in terms of structures that reflect the meaning of the sentence rather than the surface grammar of the sentence.

in Latin and the subjunctive morpheme in Latin should be ‘syntactic, phenomena’ if there are any ‘ syntactic phenomena ’ at all. Yet as we have seen, the general rules for stating such distributions must be given in terms of structures that reflect the meaning of the sentence rather than the surface grammar of the sentence.

From the fact that the arbitrary syntax position is wrong, it does not necessarily follow that the natural syntax position is right. It is logically possible to hold a ‘mixed’ position, to the effect that for some such constructions there must be arbitrary markers and for others not. However, since semantic representations for such constructions must be given independently in any adequate theory of grammar, the strongest claim that one could make to limit the class of possible grammars would be to adopt the natural syntax position and to say that there are no arbitrary markers of the sort discussed above. It is conceivable that this is too strong a claim, but it is perhaps the most reasonable position to hold on methodological grounds, for it requires independent justification to be given for choosing each proposed arbitrary marker over the independently motivated semantic representation. To my knowledge, no such justification has ever been given for any arbitrary marker, though of course it remains an open question as to whether any is possible. In the absence of any such justification, we will make the strongest claim, namely, that there exist no such markers.

It should be noted that this is a departure from the methodological assumptions made by researchers in transformational grammar around 1965, when Aspects was published. At that time it had been realized that linguistic theory had to make precise claims as to the nature of semantic representations and their relationship to syntax, but existence of semantic representations continued to be largely ignored in syntactic investigations since it was assumed that syntax was autonomous. Moreover, in Katz and Postal [36] and Aspects, a precedent had been set for the use of arbitrary markers, though that precedent was never justified. Given such a precedent, it was widely assumed that any deviation from the use of arbitrary markers required justification. However, as soon as one recognizes that (i) semantic representations are required, independent of any assumptions about the nature of grammar, and that they can be represented in terms of phrase-markers and (ii) that the autonomous syntax position is open to serious question, then the methodological question as to what needs to be justified changes. From this point of view, arbitrary markers must be assumed not to exist until they are shown to be necessary, and the autonomous syntax position can no longer be assumed, but rather must be proved.

Lakoff’s argument for the existence of abstract predicates was one of the earliest solid arguments not only against arbitrary syntax but also for the claim that the illocutionary force of a sentence is to be represented in underlying syntactic structure by the presence of a performative verb, real or abstract. She has more recently (R. Lakoff [45]) provided strong arguments for the existence of an abstract performative verb of supposing in English. Arguments of essentially the same form have been provided by Ross [66] for the existence of an abstract verb of saying in each declarative sentence of English. Thus, the importance of the argument given above for Latin goes far beyond what it establishes in that particular case, since it provides a form of syntactic argumentation in terms of which further empirical evidence for abstract predicates, performative or otherwise, can be gathered. The basic argument is simple enough:

If the same syntactic phenomena that occur in sentences with certain overt verbs occur in sentences without those verbs, and if those sentences are understood as though those verbs were there, then we conclude (1) a rule has to be stated in the cases where the real verbs occur; (2) since the same phenomenon occurs with the corresponding understood verbs, then there should be a single general rule to cover both cases; (3) since we know what the rule looks like in the case of real verbs, and since the same rule must apply, then the sentences with understood verbs must have a structure sufficiently like that of those with the overt verbs so that the same general rule can apply to both.

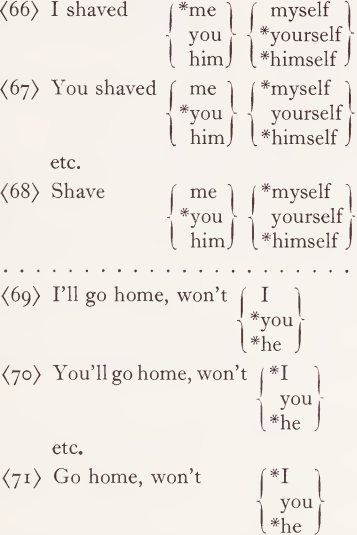

If one wishes to avoid the consequences of the Lakoff argument and of other similar arguments, there are two possible ways out. First, one can deny that the form of the argument is valid. Second, one can claim that the generalization is spurious. Let us start with the first way out. Arguments of the above form are central to generative grammar. The empirical foundations of the field rest to a very large extent on arguments of just this form. Take for example the argument that imperative constructions in English are not subjectless in underlying structure, and that they in fact have second person subjects. The sort of evidence on which this claim rests is the following:

The argument is simple enough. In sentences with overt subjects, we find reflexive pronouns in object position just in case the subjects and objects are coreferential, and nonreflexive pronouns just in case the subjects and objects are noncoreferential. We hypothesize that there is a rule of reflexivization which reflexivizes object pronouns that are coreferential with their subjects. Similarly, in tag questions, we find that as a general principle the pronominal form of the subject of the main clause occurs as the subject of the tag. In imperative sentences we find that a second person subject is understood and that a second person reflexive, but no other, shows up in object position, and that a second person nonreflexive pronoun is excluded in object position. Similarly, we find that the tags for imperative sentences contain second person subjects. We assume that all this is no accident. In order to be able to conclude that imperatives have underlying second person subjects, we need to be able to argue as follows:

If the same syntactic phenomena that occur in sentences with certain overt subjects occur in sentences without those subjects, and if those sentences are understood as though those subjects were there, then we conclude (1) a rule has to be stated in the cases where the overt subjects occur; (2) since the same phenomenon occurs with the corresponding understood subjects, then there should be a single general rule to cover both cases; (3) since we know what the rule looks like in the case of real subjects, and since the same rule must apply, then the sentences with the understood subjects must have a structure sufficiently like that of those with the overt subjects so that the same general rule can apply to both.

If arguments of this form are not valid, then one cannot conclude on the basis of evidence like the above that imperative sentences have underlying second person subjects, or any subjects at all. A considerable number of the results of transformational grammar are based on arguments of just this form. If this form of argument is judged to be invalid, then these results must all be considered invalid. If this form of argument is valid, then the results of R. LakoflP [44], [45] and Ross [66] concerning the existence of abstract performative verbs must be considered valid, since they are based on arguments of the same form. A consistent approach to empirical syntactic evidence requires that abstract performative verbs be accepted or that all results based on arguments of this form be thrown out. Whether much would be left of the field of transformational grammar if this were done is not certain.

Another way out that is open to doubters is to claim that the generalization is spurious. For example, one can claim that the occurrence of a second person reflexive in Shave yourself has nothing whatever to do with the occurrence of the second person reflexive pronoun in You will shave yourself, and that the fact that the imperative paradigms of (68) and (71) above happen to match up with the second person subject paradigms of (67) and (70) is simply an accident. If the correspondence is accidental, then there is no need to state a single general rule - in fact, to do so would be wrong. And so it would be wrong to conclude that imperative sentences have underlying subjects. If someone takes a position like this in the face of evidence like the above, rational argument ceases.

Let us take another example, the original Halle-type argument. Suppose a diehard structural linguist wanted to maintain that there was a level of taxonomic phonemics in the face of the argument given against such a position by Halle [26] (cf. Chomsky’s discussion in Fodor and Katz [16], p. 100). Halle points out that there is in Russian a rule that makes obstruents voiced when followed by a voiced obstruent. Fie then observes that if there is a level of taxonomic phonemics, this general rule cannot be stated, but must be broken up into two rules, the first relating morphophonemic to phonemic representation (1) obstruents except for c, c and x become voiced before voiced obstruents, and the second relating phonemic to phonetic representation (2) c, c and x become voiced before voiced obstruents. As Chomsky states in his discussion, ‘ the only effect of assuming that there is a taxonomic phonemic level is to make it impossible to state the generalization’. The diehard structuralist could simply say that the generalization was spurious, that there really were two rules, and that there was no reason for him to give up taxonomic phonemics. In such a case, rational argument is impossible. It is just as rational to believe in taxonomic phonemics on these grounds as it would be to maintain the arbitrary or autonomous syntax positions in the face of the examples.

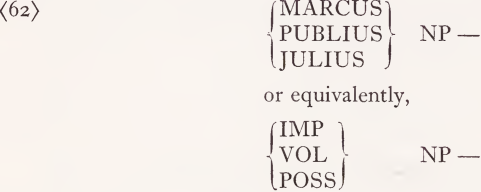

It should be noted in conclusion that transformational grammar has in its theoretical apparatus a formal device for expressing the claim that a generalization does not exist. That formal device is expressed by the curly-bracket notation. The curly-bracket notation is used to list a disjunction of environments in which a rule applies. The implicit claim made by the use of this notation is that the items on the list (the elements of the disjunction) do not share any properties relevant to the operation of the rule. From the methodological point of view, curly-brackets are an admission of defeat, since they say that no general rule exists and that we are reduced to simply listing the cases where a rule applies.

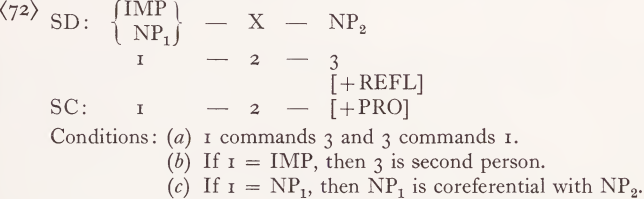

Let us take an example. Suppose one wanted to deny that imperative sentences have underlying subjects. One would still have to state a rule accounting for the fact that the only reflexive pronouns that can occur in the same clause as the main verb of an imperative sentence are second-person reflexive pronouns. A natural way to state this is by the use of curly-brackets. Thus, such a person might propose the following reflexivization rule:

Such a rule makes a claim about the nonexistence of a generalization. It claims, in effect, that the occurrence of yourself in Shave yourself has nothing to do with the occurrence of yourself in You will shave yourself', since the former would arise because of the presence of an IMP marker, while the latter would arise due to the occurrence of a coreferential NP. This, of course, is a claim to the effect that it is an accident that this construction, which allows only second person reflexives, happens to be understood as though it had a second person subject.

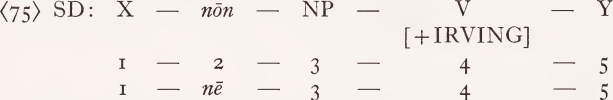

This formalism for denying the existence of a generalization could, of course, also be used in the case of the Latin examples cited above. Suppose one wanted to claim that the distribution of  with independent subjunctives had nothing to do with the distribution of

with independent subjunctives had nothing to do with the distribution of  with dependent subjunctives. Then one might attempt (sloppily) to write a rule like the following to account for the occurrence of

with dependent subjunctives. Then one might attempt (sloppily) to write a rule like the following to account for the occurrence of  :

:

Such a rule would make the claim that the occurrence of  has nothing to do with the occurrence of

has nothing to do with the occurrence of  . The former would arise due to the presence of IMP or VOL, while the latter would arise due to the presence of a verb that takes an object complement. The fact that IMP and VOL happen to mean the same thing as verbs that take object complements would have to be considered an accident.

. The former would arise due to the presence of IMP or VOL, while the latter would arise due to the presence of a verb that takes an object complement. The fact that IMP and VOL happen to mean the same thing as verbs that take object complements would have to be considered an accident.

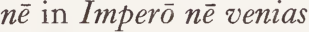

An equivalent formalism for denying the existence of generalizations is the assignment of an arbitrary feature in a disjunctive environment. For example, suppose that instead of deriving  by )73), we broke (73) up into two parts: (i) A rule assigning the arbitrary feature [ +IRVING] as follows:

by )73), we broke (73) up into two parts: (i) A rule assigning the arbitrary feature [ +IRVING] as follows:

(ii) A rule changing  in sentences with [ +IRVING] verbs:

in sentences with [ +IRVING] verbs:

One might then claim that one had a completely general rule predicting the occurrence of  occurs with [+IRVING] verbs. As should be obvious, assigning arbitrary features in this fashion is just another way of claiming that no general rule can be stated.

occurs with [+IRVING] verbs. As should be obvious, assigning arbitrary features in this fashion is just another way of claiming that no general rule can be stated.

An excellent example of the use of such a feature-assignment occurs in Klima’s important paper ‘ Negation in English’ (in Fodor and Katz [16]) in the discussion of the feature AFFECT (pp. 313 ff.). Klima notes that two rules occur in certain disjunctive environments (negatives, questions, only, if, before, than, lest), which seem vaguely to have something semantically in common. Not being able to provide a precise semantic description of what these environments have in common, he sets up a number of rules which introduce the ‘ grammatico-semantic feature ’ AFFECT, whose meaning is not explicated, in just those environments where the rules apply. He then provides a ‘general ’ formulation of the rules in terms of the feature affect. He has, of course, told us no more than that the rules apply in some disjunctive list of environments, those to which the arbitrary feature AFFECT has been assigned. If these environments do have something in common semantically (and I think Klima was right in suggesting that they do), then the general formulation of these rules awaits our understanding of just what, precisely, they do have in common.

Another example is given by Chomsky ([8], p. 39). In his analysis of the auxiliary in English, Chomsky says [the numbering is his]:

(29) (ii) Let Af stand for any of the affixes past, S, ɸ, en, ing.

Let v stand for an M or V, or have or be. . . . . Then:

Af + v → v + Af #

Note that ‘v’ does not stand for the category ‘verb’, which is represented by the capital letter ‘V’. ‘v’ and ‘V’ in this framework are entirely different symbols having nothing whatever in common, as different as  and ‘Z’.

and ‘Z’.

Af and v are arbitrary names and might equally well have been called SAM and PEDRO, since they have no semantic or universal syntactic significance. In (29 ii) Chomsky is stating two rules assigning arbitrary names to disjunctive lists of elements, and one rule which inverts the elements to which those names have been assigned. Since assigning arbitrary features like [AFFECT] is equivalent to assigning arbitrary names, (29 ii) can be stated equivalently in terms of feature-assignment rules. The following rules say exactly the same thing as (29ii):

Such a sequence of rules, in effect, makes the claim that there is no general principle governing the inversion of affixes and verbs. All that can be done is to give two lists, assign arbitrary names to the lists, and state the inversion rule in terms of the arbitrary names.

This, of course, is an absurd claim. There should be a general rule for the inversion of affixes and verbs. What should be said is that there is a universal syntactic category ‘verb’, of which M, V, have, and be are instances, and correspondingly, that there is a subcategory ‘ auxiliary verb ’ of which M (modals such as will, can, etc.), have, and be are instances. One would also need a general characterization of the notion ‘affix’ rather than just a list. The rule would then state that ‘affixes’ and ‘verbs’ invert. But this is not what (29ii) says. In the Syntactic Structures frame¬ work, M, V, have, and be are not all instances of the universal syntactic category ‘verb’. They are entirely different entities, having no more in common than Adverb, S, windmill, and into. Since the same process applies to all of them, it is impossible to state this process in a nontrivial uniform way unless M, V, have, and be are instances of the same universal category ‘ verb ’, which is what Chomsky’s analysis denies.15 Of course, it is possible to state this process in a trivial uniform way, as in (78).

On the whole, I would say that the major insights of transformational grammar have not come about through embracing rules like (73), which claim that general statements do not exist, but through eschewing such rules wherever possible and seeking out general principles. Devices like curly-brackets may be useful as heuristics when one is trying to organize data at an early stage of one’s work, but they are not something to be proud of. Each time one gives a disjunctive list of the environments where a rule applies, one is making a claim that there are no fully general principles determining the application of that rule. Over the years, curly-brackets have had a tendency to disappear as insights were gained into the nature of the phenomena being described. It may well be the case that they will turn out to be no more than artifacts of the methodological necessity of having to organize data in some preliminary fashion and of the theoretical assumption that syntax is autonomous and arbitrary.

1 See Fodor and Katz [16], pp. 503, 531 ff.; also Katz, this volume, pp. 297 ff.

2 In footnote 10 to chapter 1 of Aspects (p. 198), Chomsky says: ‘Aside from terminology, I follow here the exposition in Katz and Postal (1964). In particular, I shall assume throughout that the semantic component is essentially as they describe it. . .’ In this passage, Chomsky is ruling out the possibility that semantic representations might be phrase-markers.

3 The ‘standard theory’ is quite different in this respect from the theory assumed by JackendofT [33], who insists upon making no assumptions whatever about the nature of semantic representation. Moreover, it is not clear that Chomsky ever seriously maintained the ‘ standard theory’ as described in the passage quoted, since the main innovations of that theory - allowing semantic representations to be given in terms of phrase-markers (and thus ruling out Katzian semantics), allowing prelexical transformations, and allowing lexical semantic readings to be given as substructures of derived phrase-markers - were only made in the context of an argument to the effect that these innovations made by McCawley [48] and others were not new, but were simply variants of the ‘standard theory’. Since Chomsky does not attempt to justify this innovation, and since he does not mention it outside the context of this argument, it is not clear that he ever took such an account of the standard theory seriously. In fact, it is not clear that anyone has ever held the ‘standard theory’. Nonetheless, this theory is useful for pinpointing certain important issues in the theory of grammar, and we will use it for this purpose in subsequent discussion.

4 Postal is discussing only the strike-as-similar sense of remind. There are also two other senses: the cause-to-remember and make-think-of senses. Many speakers confuse the make-think-of and strike-as-similar senses. They are quite different. For example:

(i) Talking to you reminds me of my years as a zookeeper.

(ii) Talking to you makes me think of my years as a zookeeper.

(iii) *Talking to you strikes me as being similar to my years as a zookeeper. In addition, the make-think-of reading permits passivization, while the strike-as-similar reading does not.

(iv) John reminded me of a gorilla I once dated.

(v) I was reminded by John of a gorilla I once dated.

(iv) is ambiguous between the strike-as-similar and make-think-of readings, while (v) can only have the make-think-of reading.

5 It should be observed, incidentally, that arguments like Postal’s do not depend on complete synonymy (as in the case of remind and perceive-similar) but only on the inclusion of meaning. As long as the remind sentences contain the meaning of (9), the appropriate rules would apply and the argument would go through. If it should turn out to be the case that remind contains extra elements of meaning in addition to (9) it would be irrelevant to Postal’s argument. A mistake of this sort was made in an otherwise excellent paper by DeRijk [13], who considered examples like John forgot X and John ceased to know X, with respect to the proposal made by McCawley [48]. DeRijk correctly notes that if X = his native language, nonsynonymous sentences result. He concludes that forget could not be derived from an under¬ lying structure containing the meaning of cease to know. It would be true to say that forget cannot be derived from an underlying structure containing only the meaning of cease to know, since forget means to cease to know due to a change in the mental state of the subject. But McCawley’s conjecture, like Postal’s argument, only requires that the meaning of cease to know only be contained in the meaning of forget, which it is.

6 For a small (and arbitrarily chosen) sample of such works see Reichenbach [62], Prior [59]—[61], Geach [ 18]—[22], Montague [51], Parsons [53], [54], Hintikka [30], [31], Davidson [12], Todd [68], Castaneda [6], Follesdal [17], Rescher [63], [64], Belnap [3], Keenan [37], and Kaplan [35].

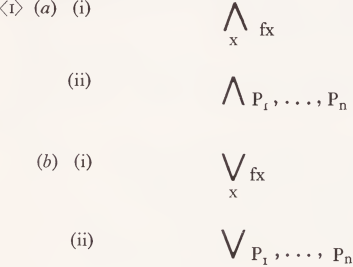

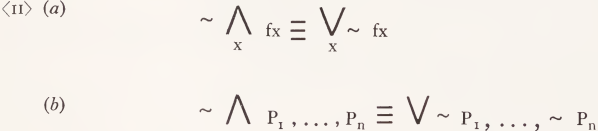

7 The similarities between universal quantifiers and conjunctions on the one hand and existential quantifiers and disjunctions on the other hand have been recognized at least since Pierce, and various notations have been concocted to reflect these similarities. Thus, universal quantification and conjunction might be represented as in (1a) and existential quantification and disjunction as in (1b):

Such a similarity of notation makes clear part of the obvious relationship between the quantifier equivalence of (11a) and DeMorgan’s Law (11b):

In the case where x ranges over a finite set, (11 a)says the same thing as (11 b). Yet despite the similarity in notation, the (ii) cases in (1) are not represented as special cases of the (i)’s and (11 a) and (11 b) are two distinct statements. There is no known notational system in which the (ii)’s are special cases of the (i)’s and in which (11 a) and (11 b) can be stated as a single equivalence, though it seems that the same thing is going oh in (11 a) and (11 b).