Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Lexemes and lexical items: the situation outside English

المؤلف:

Andrew Carstairs-McCarthy

المصدر:

An Introduction To English Morphology

الجزء والصفحة:

117-10

2024-02-06

2271

Lexemes and lexical items: the situation outside English

Is the considerable overlap between lexemes and lexical items that is a feature of English found in all languages? This question is really twofold. Firstly, are there languages where the proportion of lexical items that are not lexemes is much higher than in English? We might call these ‘idiom-heavy languages’, because relatively many of their lexical items would be phrases rather than words. Secondly, are there languages where the proportion of lexemes that are not lexical items is much higher than English? We might call these ‘neologism-heavy languages’, because relatively many of their words would be items constructed and interpreted ‘on-line’, like the English sentences at (1) and (2), rather than through identification with remembered items.

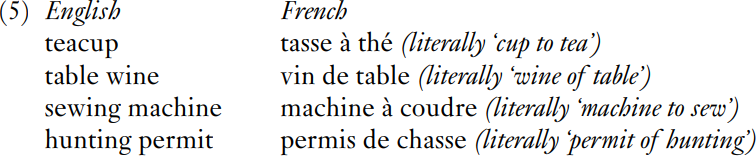

A possible example of a language of the first kind is Vietnamese, which has no inflectional morphology and almost no bound morphemes (roots or affixes), and where any distinction between morphological compounds and syntactic phrases is dubious. In Vietnamese, therefore, nearly all polymorphemic lexical items must be analyzed as phrasal idioms rather than lexemes (either compound or derived). Among languages that are likely to be more familiar to readers, French too is relatively ‘idiom-heavy’. Many concepts that are expressed by compound nouns in English are expressed by phrases in French:

It is not that French lacks compounds: for example, rouge-gorge ‘robin’ (literally ‘red-throat’), gratte-ciel ‘skyscraper’ (literally ‘scrape-sky’), and essuie-glace ‘windscreen-wiper’ (literally ‘wipe-screen’). But it is notable that these compounds are all exocentric (a robin is not a kind of throat, and a skyscraper is certainly not a kind of sky). In French, endocentric nominal compounds are relatively scarce by comparison with English; in their place, French makes greater use of phrasal idioms.

Examples of languages of the second kind are the varieties of Inuit, or Eskimo, in which many items whose meaning must be glossed by means of a sentence in English have the characteristics of a morphologically complex lexeme (or a word form belonging to such a lexeme) rather than of a larger syntactic unit. In Eskimo, many more lexemes than in English have the entirely predictable and therefore unlisted character that I ascribed to adverb lexemes such as dioeciously. It is as if Eskimo chooses to exploit the morphological route in forming many complex ex-pressions, where many languages would opt for the syntactic route.

Vietnamese and Eskimo represent, if I am right, minimizing and maximizing tendencies in the grammatical and lexical exploitation of morphology, with English somewhere in the middle. Moreover, most linguists would probably agree that the aspects of Vietnamese and Eskimo that I have emphasized render them rather untypical of human languages in general. Does that mean that, other things being equal, languages exhibit a tendency for lexical items and lexemes to converge? If so, why? Are the factors of brevity and versatility sufficient to explain it? These questions have scarcely been raised in linguistic theory, let alone answered. To pose them in an introductory textbook may seem surprising. I hope that a few readers, encountering them at the outset of university-level language study, may take them as a challenge for serious investigation!

الاكثر قراءة في Morphology

الاكثر قراءة في Morphology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)