Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Nineteenth-century philology

المؤلف:

David Hornsby

المصدر:

Linguistics A complete introduction

الجزء والصفحة:

34-2

2023-12-11

1448

Nineteenth-century philology

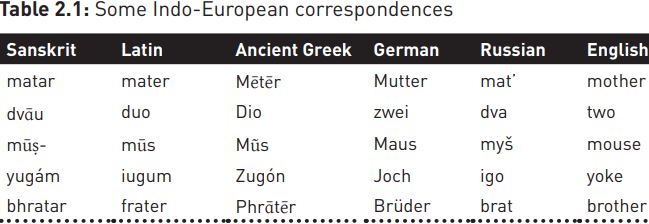

What finally helped break the hold of classical Latin in Europe was the discovery, in the late eighteenth century, of the Sanskrit scholarship of India, and notably P¯aṇini’s grammar of Sanskrit, believed to date from the fourth century BCE, which described the language of ancient sacred texts dating from some eight centuries earlier. Thanks to such codification, Sanskrit had remained, like Latin in Europe, a high-status lingua franca in India long after it had died out as a mother tongue. Bloomfield (1933: 11) describes P¯aṇini’s grammar as the first example to Europeans of ‘a complete and accurate description of a language, based not upon theory but upon observation’, i.e. one unfettered by classical Latin or Greek models. It also brought to light some striking resemblances between Sanskrit and the more familiar language families of Europe, i.e. the Romance languages, the Germanic group (e.g. German, Danish, English, Dutch) and the Slavonic (e.g. Russian, Czech, Polish, Bulgarian). As the table below demonstrates, these similarities were far too common and regular to be the result of mere chance.

Such correspondences could only be explained, argued William Jones in a famous paper to the Asiatic Society in 1786, in terms of a common ancestor, which would later become known as Indo-European.

Establishing links between languages of the Indo-European family became the prime focus of scholarly linguistic activity for most of the nineteenth century, and drew, as Friedrich Schlegel anticipated in his short 1808 work Über die Sprache und Weisheit der Inder (‘On the Language and Wisdom of the Indians’), on the model of natural history:

Where biologists found similar physical features in a number of different organisms, they concluded that, in all probability, they had been inherited from a common ancestor, even where no direct evidence for that ancestor was available. In similar vein, where philologists, working from historical written sources, found correspondences between basic lexical items that were unlikely to have been borrowed, they posited a common ancestor in Indo-European. Of course, no written evidence for Indo-European, widely believed to have been spoken some 6,000 years ago, was available, but on the basis of regularities between its descendant languages, explained in terms of sound laws, a partial reconstruction known as Proto-Indo-European (PIE) was developed.

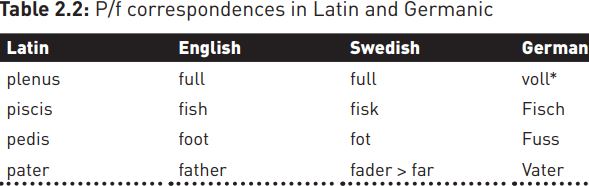

The best-known example of such correspondences is Grimm’s Law, named after Jakob Grimm, but drawing on the observations of Schlegel, Kanne and Rask, which explains a number of correspondences between Latin, Sanskrit and Germanic in terms of sound changes from Indo-European. In many words where Latin has [p], the Germanic languages have [f], as in the examples below.

Grimm explained this in terms of PIE voiceless stops [p, t, k] becoming fricatives [f, θ, x/h] in Germanic, but not in Latin, Greek or Sanskrit (compare Latin canis; Greek kýōn but German Hund; English hound). Related changes saw PIE voiced stops [b, d, g] become voiceless [p, t, k] (hence Latin duo, but English two; Swedish två).

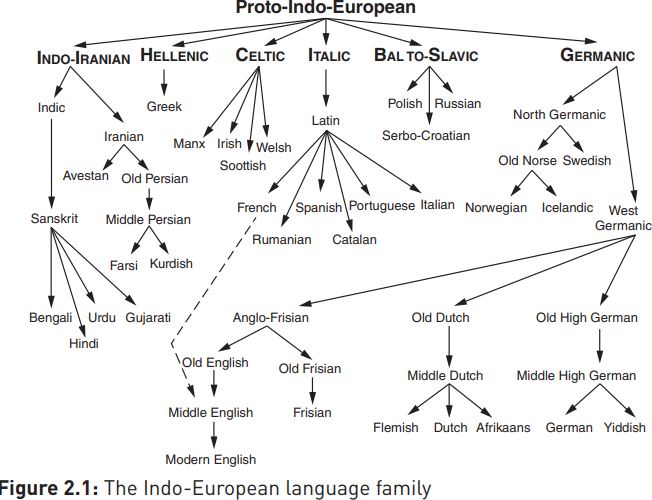

From these regular patterns of sound change, August Schleicher developed the family tree model (which owed much to botanical classification methods developed by Linnaeus), tracing the ‘parentage’ of living languages back to PIE. One version of the Indo-European family tree can be seen in the following diagram:

A common ancestor

Parallels between Sanskrit, Latin and Greek led philologists to posit a common ancestor, which was reconstructed from historical evidence as Proto-Indo-European. Family trees show historical relationships between languages, but fail to account for the effects of language contact.

The family tree model is a useful presentational tool which has been successfully applied to other language groups, for example Eskimo-Aleut, Sino-Tibetan or Austro-Asiatic, but it is nonetheless misleading in a number of respects. Firstly, it takes far too little account of language contact: the dotted arrow in the diagram above is an attempt to represent the very strong lexical influence of (Norman) French on Middle English, which belong to quite separate branches of the Indo-European trunk. The branching works well where there is a physical separation between speaker groups, allowing varieties to develop independently, as in the case of Afrikaans and Dutch, but in most cases the picture is rather messier, with branches often confusingly intertwined.

The model also presupposes relatively homogeneous varieties separating into dialects, which appear at the end branches of the tree, ignoring the fact that all languages are internally variable. Labelling a single branch as, for example, ‘English’ suggests that a homogeneous variety of that name emerged first, from which dialects were to branch off later. In fact, historically the very opposite was true: the dialectal divisions were present all along, and the codified standard language we now call ‘English’ emerged from contact between a number of them.

الاكثر قراءة في History

الاكثر قراءة في History

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)