Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Subject

المؤلف:

Jim Miller

المصدر:

An Introduction to English Syntax

الجزء والصفحة:

88-8

2-2-2022

2225

Subject

The most complex grammatical function is that of subject. Consider the example in (1).

Tigers precedes the verb. It agrees with the verb in number, as becomes clear when it is made singular: The tiger hunts its prey at night. In the active construction, it is never marked by any preposition. The corresponding full passive clause is Prey is hunted by the tigers at night; in the passive clause, the subject of (1), the tigers, turns up inside the prepositional phrase by the tigers.

The above criteria – agreement in number with the verb, never being preceded by a preposition, occurring in the by phrase in the passive – are grammatical, and the noun they pick out in a given clause is the grammatical subject of that clause. Tigers has another interesting property: it refers to the Agent in the situation described by (1). Many analysts consider that tigers refers to the Agent in the passive sentence too, although it is inside the by prepositional phrase and at the end of the sentence. They call tigers the logical subject, by which is meant that in either syntactic construction tigers denotes the Agent. That is, its role in the situation does not change.

Other analysts maintain that in the passive sentence tigers no longer denotes the Agent but rather the Path by which the action reaches and affects the prey. Such arguments lead us into a very old and unresolved controversy as to whether language corresponds directly to objective reality or whether it reflects a mental representation of the outside world. For the moment, we put this controversy aside; but it will return (possibly to haunt us) when we take up the topic of roles. All we need do here is note the assumptions that lie behind the notion of logical subject, and to understand that in any case the grammatical subject NP in an active construction of English typically denotes an Agent. This follows from the fact that most verbs in English denote actions.

A third type of subject is the psychological subject. In (1), tigers is the starting point of the message; it denotes the entities about which the speaker wishes to say something, as the traditional formula puts it. Example (1) is a neutral sentence: it has a neutral word order, and the three types of subject coincide on the NP tigers. Psychological subject and grammatical subject need not coincide. In This prey tigers hunted, the psychological subject is this prey. It is what was called ‘topic’.

In contemporary linguistic analysis, the notion of psychological subject has long been abandoned, since it encompasses various concepts that can only be treated properly if they are teased apart. Again, the details need not concern us. What is important is that in sentences such as (1) the grammatical subject noun phrase typically denotes the Agent and typically denotes the entity which speakers announce and of which they then make a predication.

It is the regular coincidence of grammatical subject, Agent and psychological subject in English and other languages of Europe that makes the notion of subject so natural to native speakers and to analysts. Here, we take the grammatical criteria to be the most important and explore them further. Consider the examples in (2).

All these examples contain infinitive phrases: to meet the PM, to reach Kashgar, to bake a cake. Such infinitives are nowadays regarded as non-finite clauses, one of their properties being that they have understood subjects: for example, Fiona is the understood subject of meet the PM; Fiona is, so to speak, doing the hoping and Fiona is the person who is to do the meeting, and similarly for Susan in (2b) and Arthur in (2c).

The infinitive meet in (2a) is dependent on the main verb hoped, and the grammatical subject of the main verb, Fiona, is said to control the understood subject of the infinitive.

In the sentences in (2), the main verbs have only one complement, the infinitive. In the examples in (3), the verbs have two complements, a noun phrase and an infinitive.

In (3a, b), the verbs persuaded and wanted are followed by a noun phrase, Arthur and Jane, and then by an infinitive phrase. These infinitive phrases too have understood subjects controlled by the noun phrases Arthur and Jane to the right of the verb; Arthur underwent the persuasion and did the baking; Jane was the target of Susan’s wishes and was to do the studying. Suppose we expand (3a) to include the ‘missing’ constituents:

Suppose we relate the infinitive to a finite clause: Arthur baked a cake. The path from the finite clause to the infinitive involves deleting a constituent; the affected constituent is always the grammatical subject of the non-finite clause, which is why analysts see the subject as pivotal to the infinitive construction.

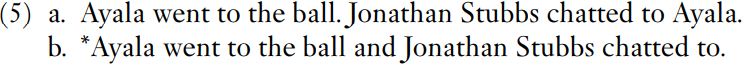

The two sentences in (4a) yield the single sentence in (4b) by the ellipsis of the grammatical subject, Ayala, in the second sentence. Only the grammatical subject can be ellipted. Example (5a) cannot be converted into (5b) by the ellipsis of the non-subject Ayala in the second sentence.

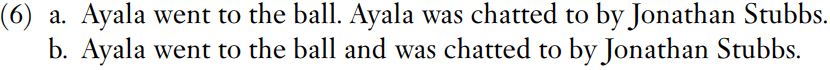

It does not matter whether the grammatical subject NP denotes an Agent, as is demonstrated by the combining of active and passive sentences in (6).

In this construction, too, the grammatical subject is pivotal, in the sense that it is a grammatical subject that is omitted on the way from the (a) to the (b) examples. Furthermore, the understood subject of the second clause in (4b) and (6b) is controlled by the initial grammatical subject.

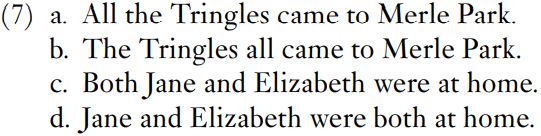

A third construction in which the grammatical subject NP is central is exemplified in (7).

In (7b), the word all is part of the noun phrase all the Tringles. That noun phrase is the subject, and all can ‘float’ out of the NP to a position next the finite verb, as in (7b). Similarly, both can be part of the subject noun phrase as in (7c) but can float to the same position, as in (7d).

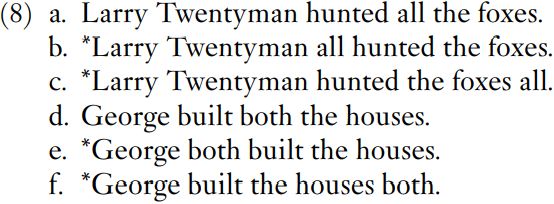

Only subject NPs allow all and both to float. In (8a), all is part of the non-subject phrase all the foxes and cannot float to the left of the finite verb, as shown by the unacceptable (8b), nor to the right, as in the unacceptable (8c). Nor can both in (8c) and (8d).

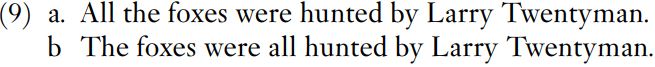

As with the missing subject in the conjoined clauses in (5) and (6), quantifiers can float out of subject noun phrases in both active and passive clauses, as shown by (9a, b)

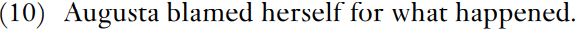

One final property of grammatical subjects is worth mentioning, namely that just as subjects control the understood subjects of non-finite clauses, so they control the interpretation of reflexive pronouns inside single clauses. This is shown in (10), where Augusta and herself refer to the same woman called Augusta.

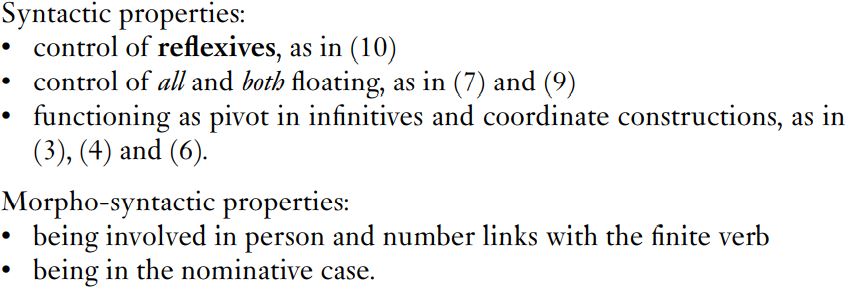

In the above discussion, we have talked of grammatical subject noun phrases as having particular properties, but to talk in this way is to take the notion of grammatical subject for granted. We present the state of affairs more accurately if we say that in English various properties attach to noun phrases: denoting an Agent, specifying the entity the speaker wishes to say something about, acting as the pivot of various constructions (coordination, infinitives, both and all floating, reflexives), being involved in person and number agreement with the finite verb. In the neutral active declarative construction of English, these properties converge on one NP, which is accorded the title of grammatical subject.

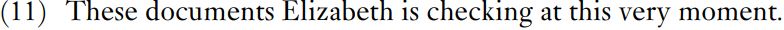

As the discussion of psychological subject showed, the properties do not always converge on one noun phrase. The psychological subject of (11) is these documents, which does not agree with is in number and person and is not the grammatical subject.

One property must be added to the list. It is not relevant to English (apart from the pronoun system) but it is central to other Indo-European languages such as Russian. The property is that of taking nominative case, as exemplified in (12).

In (12a), Ivan is in the nominative case (as the traditional formula puts it) and Mashu is in the accusative case. In (12b), Masha is in the nominative case and Ivana is in the accusative case. Analogous changes only show up in the pronouns in English, as in I pushed him and He pushed me.

We conclude this discussion of subject by listing the relevant properties and by pointing out that the list employs concepts that were important for the discussion of constructions and of word classes. In our examination of constructions, in particular the idea of constructions forming a system, we appealed to the concept of a basic construction, which was [DECLARATIVE, ACTIVE, POSITIVE]. This basic construction allows the greatest range of tense, aspect, mood and voice . Instances of this construction are the easiest to turn into relative or interrogative clauses; they take the greatest range of adverbs. They are semantically more basic than other clauses; in order to understand, for example, Kate wasn’t helping and Was Kate helping?, it is necessary to understand Kate was helping.

The list of properties that we are to establish relates to the basic construction. In the discussion of word classes, we distinguished between syntactic and morpho-syntactic properties. Subjects have the following major properties:

There are two semantic properties. One is simply that grammatical subjects typically refer to Agents. The second is that they refer to entities that exist independently of the action or state denoted by the main verb, whereas there are many verbs whose direct object does not have this property . For example, in Skilled masons built the central tower in less than a year the direct object, the central tower, denotes an entity that does not exist independently of the action for the simple reason that it is created by the activity of building. Note that the passive clause The central tower was built by skilled masons in less than a year does not contradict what has just been said. The central tower is certainly a subject and denotes the entity created by the building activity, but the passive construction is not basic.

There are two semantic properties. One is simply that grammatical subjects typically refer to Agents. The second is that they refer to entities that exist independently of the action or state denoted by the main verb, whereas there are many verbs whose direct object does not have this property . For example, in Skilled masons built the central tower in less than a year the direct object, the central tower, denotes an entity that does not exist independently of the action for the simple reason that it is created by the activity of building. Note that the passive clause The central tower was built by skilled masons in less than a year does not contradict what has just been said. The central tower is certainly a subject and denotes the entity created by the building activity, but the passive construction is not basic.

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)