تاريخ الرياضيات

الاعداد و نظريتها

تاريخ التحليل

تار يخ الجبر

الهندسة و التبلوجي

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

العربية

اليونانية

البابلية

الصينية

المايا

المصرية

الهندية

الرياضيات المتقطعة

المنطق

اسس الرياضيات

فلسفة الرياضيات

مواضيع عامة في المنطق

الجبر

الجبر الخطي

الجبر المجرد

الجبر البولياني

مواضيع عامة في الجبر

الضبابية

نظرية المجموعات

نظرية الزمر

نظرية الحلقات والحقول

نظرية الاعداد

نظرية الفئات

حساب المتجهات

المتتاليات-المتسلسلات

المصفوفات و نظريتها

المثلثات

الهندسة

الهندسة المستوية

الهندسة غير المستوية

مواضيع عامة في الهندسة

التفاضل و التكامل

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

معادلات تفاضلية

معادلات تكاملية

مواضيع عامة في المعادلات

التحليل

التحليل العددي

التحليل العقدي

التحليل الدالي

مواضيع عامة في التحليل

التحليل الحقيقي

التبلوجيا

نظرية الالعاب

الاحتمالات و الاحصاء

نظرية التحكم

بحوث العمليات

نظرية الكم

الشفرات

الرياضيات التطبيقية

نظريات ومبرهنات

علماء الرياضيات

500AD

500-1499

1000to1499

1500to1599

1600to1649

1650to1699

1700to1749

1750to1779

1780to1799

1800to1819

1820to1829

1830to1839

1840to1849

1850to1859

1860to1864

1865to1869

1870to1874

1875to1879

1880to1884

1885to1889

1890to1894

1895to1899

1900to1904

1905to1909

1910to1914

1915to1919

1920to1924

1925to1929

1930to1939

1940to the present

علماء الرياضيات

الرياضيات في العلوم الاخرى

بحوث و اطاريح جامعية

هل تعلم

طرائق التدريس

الرياضيات العامة

نظرية البيان

Calendar, Numbers in the

المؤلف:

Richards, E. G

المصدر:

Mapping Time: The Calendar and its History

الجزء والصفحة:

...

5-1-2016

1182

Calendars have always been based on the Sun, Earth, and Moon. Ancient people observed that the position of the Sun in the sky changed with the seasons. They also noticed that the stars seemed to change position in the night sky throughout the year. They saw that the Moon went through phases where it appeared to change its shape over the course of about 30 days. All of these astronomical phenomena happened regularly. As a result, people began to organize their lives around these periodic occurrences, thereby forming the basis for calendars.

Through the centuries, calendars have changed because of astronomy, politics, and religion. Over time, astronomers learned more about the precise movements of the Sun, Earth, and Moon. Politicians would often change the calendar for their own personal gain. In ancient Rome, officials would sometimes add days to the calendar to prolong their terms in office. Church officials also had specific ideas about when religious holidays should occur.

Eventually, calendars evolved into the most widely used calendar today, the Gregorian calendar. This is a calendar based on the amount of time it takes Earth to travel around the Sun (365 1/4 days). However, a year cannot be divided evenly into months, weeks, or days. So even with all of the technology available in the twenty-first century, the Gregorian calendar is still nota perfect calendar.

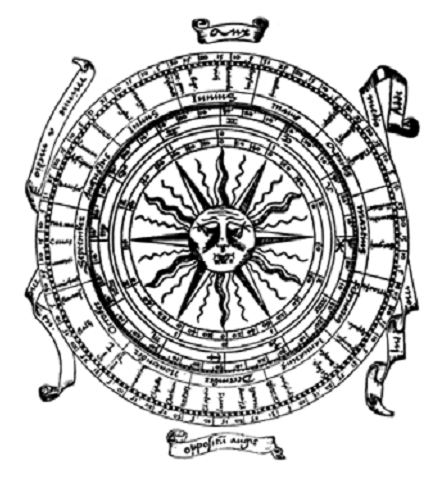

This undated calendar with Latin text tracks Venus as seen by Earth throughout the year. It depicts an unhappy Sun in the center with rings representing the Zodiac, months, dates, and Venus’ phases.

Ancient Calendars

Some of the first calendars came from ancient Babylonia, Greece, and Egypt.

Ancient Egypt and Greece date back to at least 3000 B.C.E. and Babylonia existed from the eighteenth through the sixth century B.C.E. The first written record of the division of a year, however, may have come from as far back as 3500 B.C.E. in Sumeria, which later became Babylonia.

The ancient Babylonians had a lunar calendar based on the phases of the Moon. Each month was 30 days long, the approximate time between full moons, and there were 12 months in the year, thus yielding a 360-day year (12 months x 30 days/month). However, the actual time between full moons is closer to 29.5 days, so a lunar year is 354 days (12 months x 29.5 days/month). But after only a few years, this 6-day difference would cause the seasons to occur in the wrong calendar months. To correct the calendar, the Babylonians added days or months to it when necessary. Calendars that make periodic adjustments such as this are called “lunisolar” calendars.

The ancient Greeks also used a lunisolar calendar, but with only 354 days, the same as an actual lunar year. The Greeks were also the first to adjust their calendar on a scientific basis rather than just adding days when it became necessary.

Around 3000 B.C.E, the Egyptians became the first culture to begin basing their calendar on a solar year, like the current Gregorian calendar. Although Egyptian calendars were 365 days long, astronomers eventually learned that the actual solar year had an extra one-quarter day. But an attempt to apply this knowledge to the calendar did not occur until 238 B.C.E., when Ptolemy III, King of Egypt, decreed that an extra day should be added to every fourth year to make up for the extra one-quarter day each year.

However, his decree was largely ignored and the calendar did not contain a “leap year” until 46 B.C.E., when Julius Caesar, Emperor of Rome, created the Julian Calendar.

Caesar and the Calendar

In Rome, the Roman calendar was used from the seventh century B.C.E. to 46 B.C.E. It originally had 10 months and 304 days. The year began with March and ended with December. Later, in the seventh century, Januarius and Februarius were added to the end of the year.

By 46 B.C.E., the calendar had become so out-of-step with the actual seasons that Caesar decided to make 46 B.C.E. last for 445 days to make the calendar consistent with the seasons once more. He then fixed the year at 365 days with every fourth year being a leap year with 366 days. His new calendar was called the Julian calendar. In the Gregorian calendar today, the extra day in a leap year falls at the end of February because February

was the last month of the year in the Roman calendar.

Many of the names of the months in the modern Gregorian calendar come from the Roman calendar. The fifth through tenth months of the calendar were named according to their order in the calendar—Quintilis, Sextilis, September, October, November, and December. For example, Quintilis means “fifth month” in Latin. Two of the months in the Julian calendar were later renamed—Quintilis became July, after Julius Caesar, and Sextilis became August, named after Caesar’s successor, Augustus.

When Julius Caesar changed the calendar to 365 days, he did not spread the days evenly over the months as one might expect. Therefore, February continues to have 28 days (29 in a leap year), while all other months are 30 or 31 days.

The Gregorian Calendar

The Gregorian calendar was created in 1582 by Pope Gregory XIII to replace the Julian calendar. The Julian year was 11 minutes and 14 seconds longer than a solar year. Over time, it too, no longer matched the seasons and religious holidays were occurring in the wrong season. In 1582, the vernal equinox, which occurred on March 21 in 325 C.E., occurred 10 days early. Pope Gregory XIII consequently dropped 10 days from the calendar

to make it occur again on March 21. In addition, he decided that every century year (1500, 1600, etc.) that was evenly divisible by 400 should be a leap year. All other century years remained common years (365 days).

The Gregorian calendar was slowly accepted by many European and western countries. As different countries adopted the calendar, it went through some interesting changes. For example, Britain did not accept the calendar until 1752. Previously, the British began a new year on March 25.

In order to begin 1752 on January 1, the period January 1 through March 24 of 1751 became January 1 through March 25 of 1752, and 1751 lasted only from March to December.

Other Calendars

In addition to the Gregorian calendar, many religious calendars exist. For example, the Islamic calendar is a lunar calendar of 354 days. Leap years occur every 2 or 3 years in a 30-day cycle. Many mathematical equations exist for converting dates from religious calendars to the Gregorian calendar.

Many people have proposed changing to a more standard calendar in which the months would have an equal number of days and calendar dates would fall on the same days of the week from year to year. But changing the calendar faces stiff opposition because national and religious holidays would have to be changed.

______________________________________________________________________________________________

Reference

Richards, E. G. Mapping Time: The Calendar and its History. New York: Oxford University Press, Inc., 1998.

Steel, Duncan. Marking Time: The Epic Quest to Invent the Perfect Calendar. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2000.

الاكثر قراءة في الرياضيات في العلوم الاخرى

الاكثر قراءة في الرياضيات في العلوم الاخرى

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)