Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

The course and the assessment strategies

المؤلف:

Carmel McNaught & Paul Lam & Daniel Ong & Leo Lau

المصدر:

Enhancing Teaching and Learning through Assessment

الجزء والصفحة:

P258-C22

2025-07-16

228

The course and the assessment strategies

This study is part of a three-year project that began in the year 2002 aimed at implementing a case-based approach to teaching and learning in a selected set of science courses in Hong Kong universities. As using cases to teach science subjects is a relatively new idea in Hong Kong, the project began by writing cases suitable for the context using industrial research data gathered in the Advanced Surface and Materials Analysis Centre in the Department of Physics at The Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK). Then, a number of trial runs were carried out on various undergraduate and postgraduate courses in the Material Science stream of the Department (six case-based courses have been completed thus far). Earlier work on the project is reported in McNaught et al. (2005).

As the project progressed, it became apparent that we needed to focus as much attention on the design of assessment as we were on the writing of cases. This topic reports one of the project's attempts at designing and implementing case-based assessment in a case-based Year 1 Surface Science course held in the second term of the 2003-2004 academic year at CUHK. There were 22 students on the course which was separated into two main phases. The first phase used a group-based peer teaching strategy in which the students were required to take part in some cooperative learning activities, centred around four important topics of the subject. The students self-studied material, discussed the concepts in their own small group and then taught their classmates. They were provided with readings and a detailed study guide in order to scaffold (e.g. Jonassen, 1999) their learning. This first phase was seen as formative, and the presentations were set as important 'practice'.

The second phase of the course involved the introduction of a Materials Science case. Students discussed in groups, searched for information, made decisions concerning the problems posted in the case, and lastly presented their ideas to the whole class. There were thus two rounds of class presentations. However, the assessment for the course was focused on the second phase where the case was analyzed and presented.

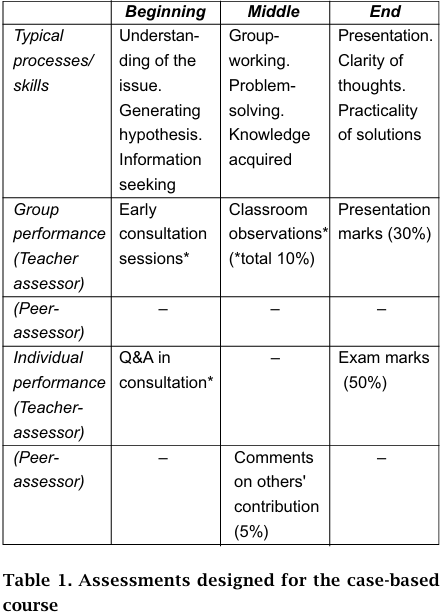

Care was taken to implement the assessments for this Year 1 course in ways that matched the overall case-based approach such that the assessments: shifted from being solely teacher-centred to actively involving students' contributions; had a mechanism to distinguish not only group but also individual performances; and were able to monitor students' capabilities in a range of learning processes and skills.

In order to achieve these aims, the following strategies were implemented. To encourage student contribution to the assessment, all assessment criteria were laid down at the beginning of the course and a briefing session was held to introduce and clearly explain the format of the course and the relatively complicated assessment model. Students were asked to comment on the assessments. Their feedback led to refinement of the format and timetabling of the assessments. All cases were coupled with very clear statements of requirements followed by a detailed marking scheme as a result of the students' opinions. Students' contribution was also seen in the peer-assessment activities introduced to the course: group members graded each other, based on their participation and contribution within the group.

To enact a mechanism which distinguished not only group but also individual performances, the teacher of the course introduced consultation sessions in which he monitored individual performances. There was a course-end examination testing knowledge that the individual students learnt both from doing their own projects and from their peers through their presentations. There was also peer feedback of contributions from individual members in a group. The group performance was monitored by group presentations and reports.

To monitor students' capabilities in a range of learning processes and skills, the grades were not only allocated to the products, but were also allocated to the intervening processes. The teacher monitored the abilities of the students in understanding the issues in the case, generating a hypothesis on their own, and searching for information in the early consultation sessions in which he met each of the groups in turn. He then monitored the groups' group-working skills, problem-solving abilities and the knowledge they learnt in the classroom activities when he gave time to the students to have group discussions in class. Lastly, analytic skills and presentation skills were demonstrated on the occasion when the students presented their solutions to the cases at the end of the course.

There was a careful record kept of each interaction between the teacher and students, and detailed mark sheets were maintained.

The course-end examination was also changed to cope with the case-based nature of the course. The teacher had deliberately included more demanding questions that called for understanding of a situation, application of theories and concepts, and solving problems.

The assessment mechanism is captured in Table 1, which shows the various assessment methods (teacher-grading or peer-grading) employed in the course to monitor both the group and the individual performances.

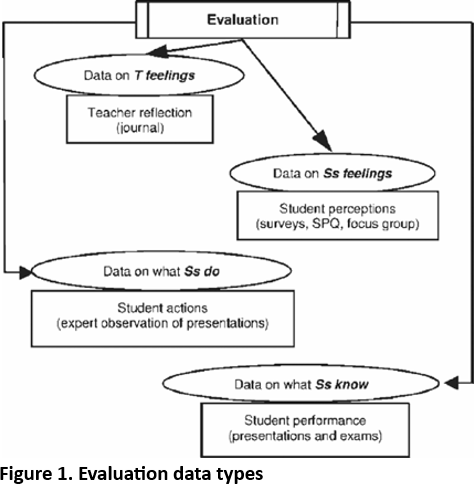

Multiple sources of data were used to evaluate the course, as illustrated in Figure 1 (after the model of Lam & McNaught, 2004). The data covers feedback of both the teacher and students, as well as the performance of the students.

The teacher data included collection of the teacher's reflection and discussions with other research members during observations of the class in action. The student data were rich. The revised two-factor Study Process Questionnaire (SPQ) was used (Biggs et al., 2001); in this version, the achieving scale of the first version (Biggs 1987) is incorporated into the deep scale. The SPQ is a 20-item questionnaire which provides a measure of students' approaches to learning on two scales (surface and deep). The SPQ was administered twice: once at the beginning of the course and again at the end, to monitor changes in learning motivation and strategies. Written surveys were also administered once in mid-term (response rate 85%) and once at the end of the course (response rate 95%) to collect students' opinions on the teaching and assessment approach. The mid-term survey had 15 Likert-scale items and three open-ended questions and was administered at the end-of March, 2004, in class. The main focus of this survey was the first phase of the course about self-studying and peer-teaching. The course-end survey consisted of nine Likert-scale items and four open-ended questions. It was administered at the end of April, 2004, and focused on both the case-handling experience of the second phase and students' overall comments on the whole approach used in the course. A one-hour focus-group meeting was held with 13 randomly-selected students from the course to discuss their feelings towards it. Lastly students' performance data were also collected. Marks were obtained for: students' presentations, case reports and final examination results.

The evaluation looked at the appropriateness of the new assessment strategies, as well as the performance of the case-based approach in supporting students to attain the desired learning outcomes.

الاكثر قراءة في Teaching Strategies

الاكثر قراءة في Teaching Strategies

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام) قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر مجموعة قصصية بعنوان (قلوب بلا مأوى)

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر مجموعة قصصية بعنوان (قلوب بلا مأوى)