Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

A case study of the semantics of clear - The framework – a version of Gunlogsons model of context update

المؤلف:

GINA TARANTO

المصدر:

Adjectives and Adverbs: Syntax, Semantics, and Discourse

الجزء والصفحة:

P313-C10

2025-05-01

1053

A case study of the semantics of clear - The framework – a version of Gunlogsons model of context update

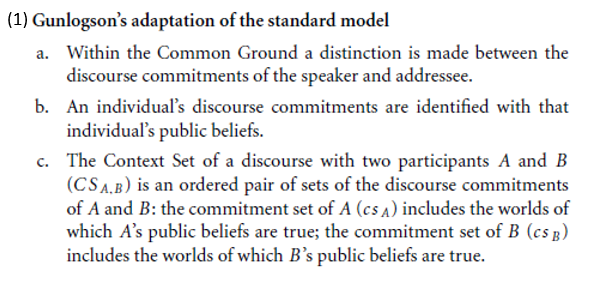

The starting point for the analysis of discourse adjectives is Gunlogson’s 2001 version of a standard Stalnakerian model of context update. The basic idea of Gunlogson’s model is outlined in (1).

The context as defined in (1c) represents a departure from more standard implementations of a Stalnakerian model. Gunlogson takes the distinct discourse commitments of individual participants to be basic, and she uses this to derive a standard Stalnakerian context set. This isn’t to say that one cannot derive the individual commitments from the standard Stalnakerian conception of the context of a discourse, but in order to talk about discourse adjectives, access to individual commitments is crucial. Gunlogson’s model is a natural choice for the ease of exposition.

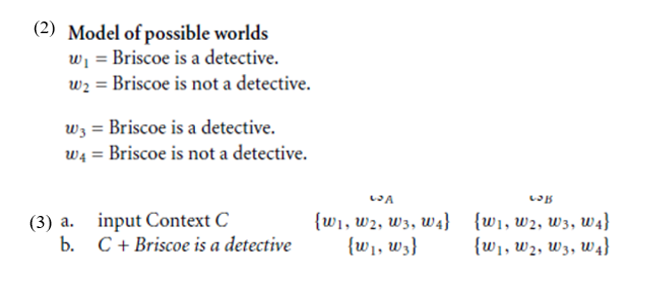

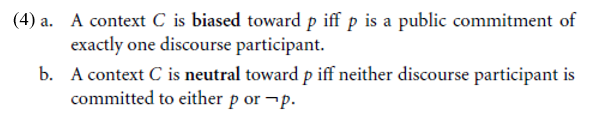

An example of the effect an utterance of Briscoe is a detective has on the common ground is shown in (3). The model of possible worlds under consideration is given in (2). The context set in (3) separates the commitment sets (the worlds consistent with the public beliefs) of A and B.

In (3a) all of the worlds in the model in (2) are included as live options for both A and B. Update with A’s assertion of Briscoe is a detective removes w2 and w4, worlds in which Briscoe is not a detective, from A’s individual commitment set. The context in (3b) is biased toward the truth of the proposition expressed by Briscoe is a detective. Bias is a technical term introduced by Gunlogson, to contrast with the notion of contextual neutrality. Definitions of contextual bias and neutrality are provided in (4).

By these definitions, before A’s utterance of Briscoe is a detective, the context in (3a) is neutral with respect to the proposition expressed. The effect of the utterance is a context that is biased toward the proposition expressed by Briscoe is a detective.

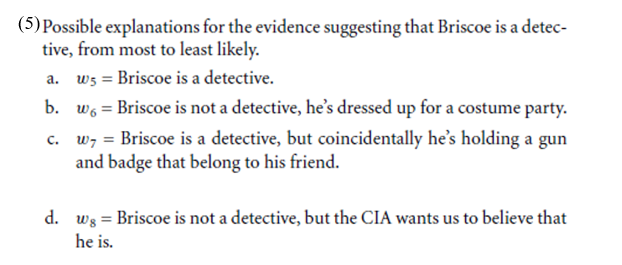

With this terminology established, it is possible to proceed with an analysis of clear. The starting point is the convergence of three observations about discourse adjectives: first, that they are not factive; second, that they have experiencers; and third, that there are a number of possibilities for the way the world might be, and that these are ordered in terms of their plausibility. For instance, regarding the proposition that Briscoe is a detective (5), in any given world the possible explanations might include that Briscoe is a detective, as in w5, that he is not a real detective, but he dressed like one to attend a costume party, as in w6, or perhaps even the more unlikely alternative in w8, that Briscoe is not a detective at all, but the CIA wants us to believe that he is.

To consider a situation in which an utterance of It is clear that Briscoe is a detective might be made, imagine that the propositions expressed by the sentences in (6) are true, and that they have just been uttered by B.

Nothing in the sentences in (6) rules out any of the possible worlds given in (28). But because in some of these worlds Briscoe is a detective, update with It is clear that Briscoe is a detective will do some work. It will at least eliminate those worlds in which Briscoe is not a detective. This result is immediately suspicious because, as was shown in (2) and (3), simply asserting Briscoe is a detective will achieve the same result.

The question that emerges is the following: Why not just assert that Briscoe is a detective? Why ever assert that it is clear that Briscoe is a detective? The answer to this question is clear. A speaker might be reluctant to assert that Briscoe is a detective because Briscoe might not be a detective. There are other live possibilities. Since it is known from Grice that it is uncooperative for a speaker to assert something for which she lacks sufficient evidence, it would be uncooperative to claim that Briscoe is a detective in the absence of absolute certainty.

If this analysis is on the right track, it points to the conclusion that clarity is asserted only in contexts in which there is some lingering uncertainty about whether the complement is in fact true. Due to the lingering uncertainty about Briscoe’s status as a detective, an utterance of It is clear that Briscoe is a detective should not be felicitous, but it is. The problem is that discourse participants may not be sure how strong the evidence used to conclude that a proposition is true needs to be in order to support a determination that a proposition is true. This is what Barker and Taranto identified as the paradox of asserting clarity.

The key to resolving this paradox depends on appreciating how the grammar deals with degrees of probability. In other words, the appropriateness of asserting clarity depends on the degrees of probability of the different explanations of the facts. An assertion of clarity depends on the likelihood of the probability of a proposition p as determined by a discourse participant who is evaluating evidence in support of p. Situations in which the applicability of a predicate depends on degrees are well known in the literature. This is an example of vagueness (Fine 1975; Williamson 1994, 1999; Kennedy 1999b), or the observation that in a given situation, it’s not always clear how clear a proposition needs to be to count as clear.

الاكثر قراءة في Linguistics fields

الاكثر قراءة في Linguistics fields

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)