Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Sonority

المؤلف:

Mehmet Yavas̡

المصدر:

Applied English Phonology

الجزء والصفحة:

P135-C6

2025-03-11

797

Sonority

Before we start using the concept, we need to define what sonority is. This, in itself, is not an easy task, as it is also far from being uncontroversial. For pedagogical purposes, we will keep it as straightforward as possible. The sonority of a sound is primarily related to the degree of opening of the vocal tract during its articulation. The more open the vocal tract is for a sound, the higher its sonority will be. Thus vowels, which are produced with a greater degree of opening, will be higher on the sonority scale than fricatives or stops, which are produced either with a narrow opening or with a complete closure of the articulators. The second, and relatively secondary (ancillary), dimension is the sound’s propensity for voicing. This becomes relevant when the stricture (degree of opening) is the same for two given sounds; the sound that has voicing (e.g. voiced fricative) will have a higher degree of sonority than its voiceless counterpart (e.g. voiceless fricative). Putting all these together, we can say that low vowels (/æ, ɑ/), which have the maximum degree of opening, will have the highest sonority; and voiceless stops, which have no opening and no voicing, will have the lowest sonority. The remaining sounds will be in between.

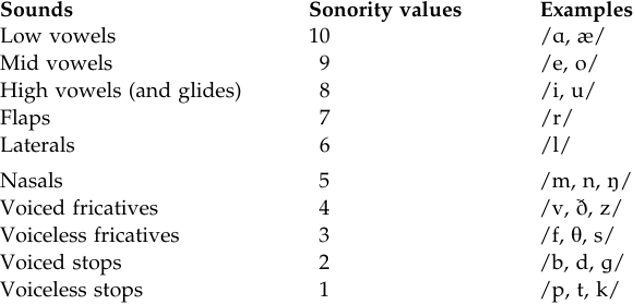

One finds different hierarchies of sonority in different books and manuals. However, the differences are in details rather than the basic relative ordering. We adopt the following 10-point scale suggested by Hogg and McCully (1987):

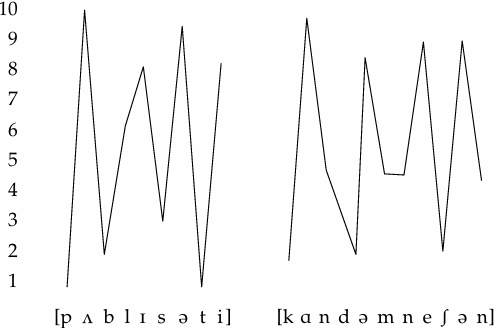

Having stated the relative sonority of sounds, we are now ready to look at the number of syllables in words as peaks of sonority. In auditory terms, the sonority peak is more prominent than the surrounding segments. Since vowels and diphthongs are higher in sonority than other segments, they typically occupy the peak positions in syllables. We show this with the following displays for publicity and condemnation:

The principle of peaks of sonority correctly identifies the number of syllables, four, in these two cases.

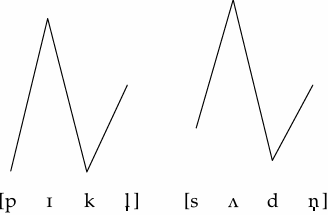

As we saw earlier, in English we can have syllables that do not contain a vowel. In these cases, the most sonorant consonant will be the syllable peak (i.e. syllabic consonant):

Since the existence of syllabic consonants is due to the deletion of the reduced vowel [ə], they are confined to unstressed syllables. In stressed syllables, we always have full vowels that will assume the syllabic peaks; this leaves no chance for the consonant to be syllabic.

Although the principle of equating the sonority peaks to the number of syllables would hold for thousands of English words, it does not mean that it is without exceptions. We must acknowledge the fact that some English onset clusters with /s/ as the first consonant (e.g. stop [stɑp]), and coda clusters with /s/ as the last consonant (e.g. box [bɑks]), do violate this principle.

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)