النبات

مواضيع عامة في علم النبات

الجذور - السيقان - الأوراق

النباتات الوعائية واللاوعائية

البذور (مغطاة البذور - عاريات البذور)

الطحالب

النباتات الطبية

الحيوان

مواضيع عامة في علم الحيوان

علم التشريح

التنوع الإحيائي

البايلوجيا الخلوية

الأحياء المجهرية

البكتيريا

الفطريات

الطفيليات

الفايروسات

علم الأمراض

الاورام

الامراض الوراثية

الامراض المناعية

الامراض المدارية

اضطرابات الدورة الدموية

مواضيع عامة في علم الامراض

الحشرات

التقانة الإحيائية

مواضيع عامة في التقانة الإحيائية

التقنية الحيوية المكروبية

التقنية الحيوية والميكروبات

الفعاليات الحيوية

وراثة الاحياء المجهرية

تصنيف الاحياء المجهرية

الاحياء المجهرية في الطبيعة

أيض الاجهاد

التقنية الحيوية والبيئة

التقنية الحيوية والطب

التقنية الحيوية والزراعة

التقنية الحيوية والصناعة

التقنية الحيوية والطاقة

البحار والطحالب الصغيرة

عزل البروتين

هندسة الجينات

التقنية الحياتية النانوية

مفاهيم التقنية الحيوية النانوية

التراكيب النانوية والمجاهر المستخدمة في رؤيتها

تصنيع وتخليق المواد النانوية

تطبيقات التقنية النانوية والحيوية النانوية

الرقائق والمتحسسات الحيوية

المصفوفات المجهرية وحاسوب الدنا

اللقاحات

البيئة والتلوث

علم الأجنة

اعضاء التكاثر وتشكل الاعراس

الاخصاب

التشطر

العصيبة وتشكل الجسيدات

تشكل اللواحق الجنينية

تكون المعيدة وظهور الطبقات الجنينية

مقدمة لعلم الاجنة

الأحياء الجزيئي

مواضيع عامة في الاحياء الجزيئي

علم وظائف الأعضاء

الغدد

مواضيع عامة في الغدد

الغدد الصم و هرموناتها

الجسم تحت السريري

الغدة النخامية

الغدة الكظرية

الغدة التناسلية

الغدة الدرقية والجار الدرقية

الغدة البنكرياسية

الغدة الصنوبرية

مواضيع عامة في علم وظائف الاعضاء

الخلية الحيوانية

الجهاز العصبي

أعضاء الحس

الجهاز العضلي

السوائل الجسمية

الجهاز الدوري والليمف

الجهاز التنفسي

الجهاز الهضمي

الجهاز البولي

المضادات الميكروبية

مواضيع عامة في المضادات الميكروبية

مضادات البكتيريا

مضادات الفطريات

مضادات الطفيليات

مضادات الفايروسات

علم الخلية

الوراثة

الأحياء العامة

المناعة

التحليلات المرضية

الكيمياء الحيوية

مواضيع متنوعة أخرى

الانزيمات

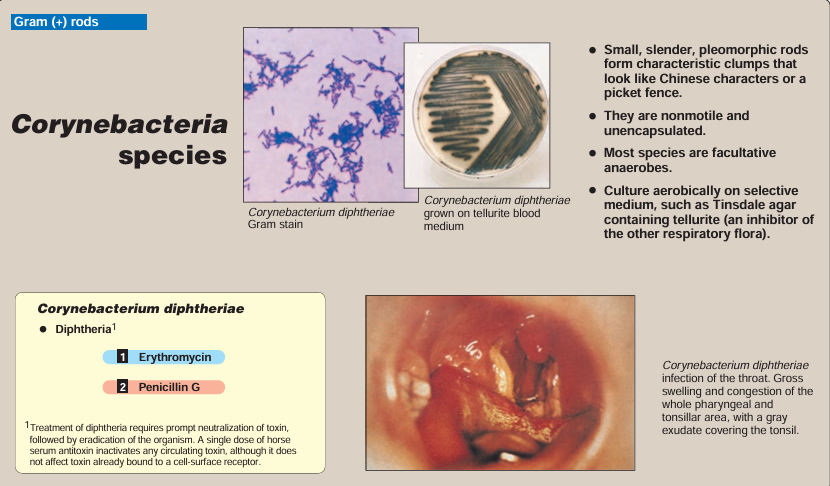

Corynebacterium diphtheriae

المؤلف:

Cornelissen, C. N., Harvey, R. A., & Fisher, B. D

المصدر:

Lippincott Illustrated Reviews Microbiology

الجزء والصفحة:

3rd edition , p91-94

2025-01-21

1118

Diphtheria, caused by C. diphtheriae, is an acute respiratory or cutaneous disease and may be life threatening. The development of effective vaccination protocols and widespread immunization beginning in early childhood has made the disease rare in developed countries, and few present-day United States clinicians have seen a case of the disease. However, diphtheria is a serious disease throughout the world, particularly in those countries where the population has not been immunized.

1. Epidemiology:

C. diphtheriae is found in the throat and nasopharynx of carriers and in patients with diphtheria. This disease is a local infection, usually of the throat, and the organism is primarily spread by respiratory droplets, usually by convalescent or asymptomatic carriers. It is less frequently spread by direct contact with an infected individual or a contaminated fomite.

2. Pathogenesis:

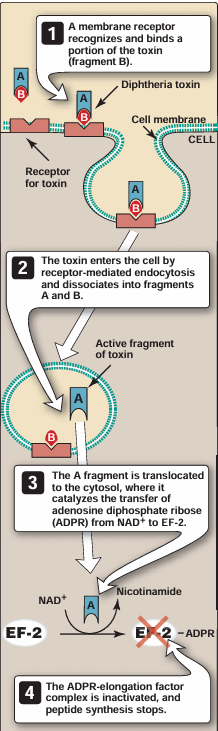

Diphtheria is caused by the local and systemic effects of a single exotoxin that inhibits eukaryotic protein synthesis. The toxin molecule is a heat-labile polypeptide that is composed of two fragments, A and B. Fragment B binds to susceptible cell membranes and mediates the delivery of fragment A to its target. Inside the cell, fragment A separates from fragment B and catalyzes a reaction between nicotine adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) and the eukaryotic polypeptide chain elongation factor, EF-21 (Figure 1). The toxin is encoded on a β-corynephage and only those strains in which the phage is integrated into the C. diphtheriae chromosome produce toxin. Toxin gene expression is also regulated by environmental conditions. Low iron conditions induce toxin expression, whereas high iron conditions repress toxin production.

Figure 1 Action of diphtheria toxin. NAD+ = nicotine adenine dinucleotide; EF-2 = eukaryotic polypeptide chain elongation factor

3. Clinical significance:

Infection may result in one of two forms of clinical disease, respiratory or cutaneous, or in an asymptomatic carrier state

a. Upper respiratory tract infection: Diphtheria is a strictly localized infection, usually of the throat. The infection produces a distinctive thick, grayish, adherent exudate (pseudomembrane) that is composed of cell debris from the mucosa and inflammatory products (. It coats the throat and may extend into the nasal passages or downward in the respiratory tract, where the exudate sometimes obstructs the airways, even leading to suffocation. As the disease progresses, generalized symptoms occur caused by production and absorption of toxin (Figure 2). Although all human cells are sensitive to diphtheria toxin, the major clinical effects involve the heart and peripheral nerves. Cardiac conduction defects and myocarditis may lead to congestive heart failure and permanent heart damage. Neuritis of cranial nerves and paralysis of muscle groups, such as those that control movement of the palate or the eye, are seen late in the disease.

Fig2. Diphtheria with marked swelling of the lymph nodes in the neck.

b. Cutaneous diphtheria: A puncture wound or cut in the skin can result in introduction of C. diphtheriae into the subcutaneous tissue, leading to a chronic, nonhealing ulcer with a gray mem brane. Rarely, exotoxin production leads to tissue degeneration and death.

4. Immunity:

Diphtheria toxin is antigenic and stimulates the production of antibodies that neutralize the toxin’s activity. [Note: Formalin treatment of the toxin produces a toxoid that retains the antigenicity but not the toxicity of the molecule. This is the material used for immunization against the disease.

5. Laboratory identification:

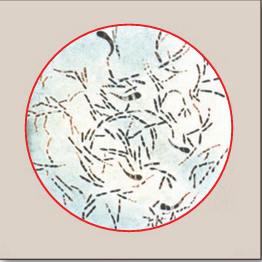

The presumptive diagnosis and decision to treat for diphtheria must be based on initial clinical observation. Diphtheria should be considered in patients who have resided in or traveled to an area in which diphtheria is prevalent, when they have pharyngitis, low-grade fever, and cervical adenopathy (swelling of the neck). Erythema of the pharynx progressing to adherent gray pseudomembranes increases suspicion of diphtheria. However, a definitive diagnosis requires isolation of the organism, which must then be tested for virulence using an immunologic precipitin reaction to demonstrate toxin production. C. diphtheriae can be isolated most easily from a selective medium, such as Tinsdale agar , which contains potassium tellurite, an inhibitor of other respiratory flora, and on which the organism produces several distinctive black colonies with halos . C. diphtheriae from clinical material or culture has a distinctive morphology when stained, for example, with methylene blue. This morphology includes characteristic bands and reddish (polychromatic) granules that are often seen in thin, sometimes club-shaped rods that appear in clumps, suggestive of Chinese characters or picket fences (see Figure 3). This presentation is often referred to as a “palisade arrangement” of cells. Initial decision to treat for diphtheria must be based on clinical observation. Culture and assay for toxin production are required for confirmation of the diagnosis.

Fig3. Corynebacterium diphtheriae.

6. Treatment:

Treatment of diphtheria requires prompt neutralization of toxin, followed by eradication of the organism. A single dose of horse serum antitoxin inactivates any circulating toxin, although it does not affect toxin already bound to a cell-surface receptor. [Note: Serum sickness caused by a reaction to the horse protein may cause complications in approximately 10 percent of patients.] C. diphtheriae is sensitive to several antibiotics, and passive immunization with preformed diphtheria toxin antibodies is a mandatory part of treatment of diphtheria. Because diphtheria is highly contagious, suspected diphtheria patients must be isolated. Antibiotic treatment, such as erythromycin or penicillin (Figure 4), slows the spread of infection and, by killing the organism, prevents further toxin production. Supportive care directed especially at respiratory and cardiac complications is an essential part of the management of patients with diphtheria.

Fig4. Summary of Corynebacterium diphtheriae disease. 1 2 Indicates first-line drugs; B. indicates alternative drugs.

7. Prevention:

The cornerstone of diphtheria prevention is immunization with toxoid, usually administered in the DTaP triple vac cine, together with tetanus toxoid and pertussis antigens . The initial series of injections should be started in infancy. Booster injections of diphtheria toxoid (with tetanus toxoid) should be given at approximately 10-year intervals throughout life. The control of an epidemic outbreak of diphtheria involves rigorous immunization and a search for healthy carriers among patient contacts.

الاكثر قراءة في البكتيريا

الاكثر قراءة في البكتيريا

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)