Limiting lexical levels

One major problem for Lexical Phonology has been the proliferation of lexical levels, as evidenced especially in recent analyses of English like Halle and Mohanan (1985). However, Booij and Rubach (1987) advocate a restrictive, principled division of the English lexicon into one cyclic and one postcyclic level (2.25), plus postlexical rules.

(2.25) LEVEL1: Class I derivation, irregular inflection

Cyclic phonological rules

LEVEL2: Class II derivation, compounding, regular inflection

Postcyclic phonological rules

This model of lexical organization is claimed to be readily generalizable to Dutch and Polish, and may even be universal, although further investigation is clearly required. However, languages may vary along certain parameters; for instance, English has both morphological and phonological rules on Level 2, whereas Dutch and Polish seem to require all word-formation rules to be ordered on cyclic Level 1. Such limited cross-linguistic variation can easily be accommodated within the revised model.

It is clear that such a principled limitation of the number of strata is desirable. However, Halle and Mohanan (1985) have produced data which, they claim, necessitates the four-way division of the lexicon shown in (2.26). In view of this evidence, can a reduction to two lexical levels be achieved?

(2.26) LEVEL1: Class I derivation, irregular inflection

Stress, Trisyllabic Shortening ...

LEVEL2: Class II derivation

Vowel Shift, Velar Softening ...

LEVEL3: Compounding

Stem-Final Lengthening and Tensing

LEVEL4: Regular inflection

/l/-Resyllabification

The arguments presented by Halle and Mohanan (1985) and Mohanan (1986) involve the supposed cyclicity of Strata 1, 3 and 4 in English, as against non-cyclic Stratum 2, and the existence of four phonological rules which appear to require a four-stratum lexicon to ensure correct application. This evidence is exclusively phonological, already a tacit admission of defeat in a supposedly integrational theory. Morphological evidence for a division of Class I from Class II derivational affixes is very strong (Siegel 1974, Allen 1980), but similar evidence for a division of Class II derivation, compounding and regular inflection is at best tenuous and at worst non-existent. For instance, Kiparsky (1982) classed compounding and Class II derivation together as Level 2 phenomena, on the grounds that each could provide input to the other process (see (2.27)).

(2.27) [[[neighbor]hood][gang]]

=affixation → compounding

[re[[air][condition]]]

=compounding → affixation

This mutual feeding relationship is recognized by Halle and Mohanan who, however, wish to differentiate Strata 2 and 3 for phonological reasons. They consequently propose that Class II derivation takes place on Stratum 2 and compounding on Stratum 3, but introduce a device, the Loop, which `allows a stratum distinction for the purposes of phonology, without imposing a corresponding distinction in morphological distribution' (1985: 64). Thus, compounds may be looped back into the Level 2 morphology to acquire Class II affixes.

The separation of compounding from regular inflection (Level 2 versus 3 in Kiparsky 1982, 3 versus 4 in Halle and Mohanan) was originally justified by the assumption that inflections like plural /S/ appear only `outside' compounds, i.e. on the final stem, as shown in (2.28).

(2.28) *motorsway service station

*motorways service station

*motorway services station

motorway service stations

However, it is now clear that this assumption was mistaken: the plural inflection appears `inside' compounds (2.29), albeit under limited circumstances (Sproat 1985). Sproat proposes that compounding and inflection should occupy a single stratum, and that `The left member of a compound must be unmarked for number, unless the plural is interpreted collectively or idiosyncratically.'

(2.29) systems analyst human subjects committee

ratings book parts department

Since compounding and Class II derivation must be allowed to be interspersed, and compounding and regular inflection also interact, there seems to be no morphological motivation for a Stratum 2 versus 3 versus 4 distinction for English. If compounding, inflection and Class II derivation are to share a single stratum, however, how are regular inflections to be restricted to word-final position, with no Class II derivational suffixes attaching to their right?

Borowsky (1990: 254) notes that sequences of regular inflection plus Class II suffix may, in fact, be permissible in certain forms, like year-ningly and lovingly; these could be generated in Halle and Mohanan's model only by proposing a second loop, this time from Level 4 to Level 2. In cases where a restriction holds on the position of regular inflections within the word, appropriate sequencing constraints would have to be formulated. Such constraints will be independently necessary in any case, as Giegerich (in press) also argues, since certain Class II derivational affixes do not appear outside others;-ful cannot follow-ness, for example (*wearinessful,*happinessful). Consequently, the solution need not lie in a stratal distinction.

We now return to Halle and Mohanan's phonological arguments for a four-level lexicon, beginning with cyclicity. Their Stratum 1 is clearly cyclic, like the initial level in other lexical phonologies of English (Kiparsky 1982, 1985; Booij and Rubach 1987); some evidence for this is that the stress rules, which are situated on Level 1, are generally agreed to operate cyclically, and that rules like Trisyllabic Laxing/Shortening clearly obey the Strict Cyclicity Condition. Halle and Mohanan also provide evidence for the non-cyclic nature of Stratum 2. First, they argue that Stem-Final Tensing (which operates on Stratum 2 in their dialects A and B, although it is ordered on Stratum 3 for Dialect C ± see below and also Halle and Mohanan 1985: 59-62) would produce the wrong output if applied cyclically. In Dialects A and B, Tensing occurs word-finally, before inflections, stem-finally in compounds, and before Class II derivational affixes, except-ful and-ly; Halle and Mohanan's Tensing rule is given in (2.30). It should be noted that this rule affects only tenseness: Halle and Mohanan generally separate lengthening and tensing processes, and regard length as the underlying dichotomizing feature in their English vowel system, with tenseness introduced by a redundancy rule during the course of the derivation.

except before-ly,-ful

(Halle and Mohanan 1985: 67)

Cyclic operation of Stem-Final Tensing would yield the derivation in (2.31).

If, however, the Tensing rule is allowed to apply only after all Stratum 2 morphology, and thus after the affixation of-ly, the correct output, [hæpɪlī], will be produced. Halle and Mohanan conclude that, since in their view cyclicity is a property of strata and not of individual rules, Stratum 2 must be non-cyclic. The hypothesis that Stratum 2 is non cyclic for English is supported by the fact that Stratum 2 phonological rules like Velar Softening and Vowel Shift, in their traditional SGP formulations, do not obey the SCC. Vowel Shift, for instance, affects divine and serene, while Velar Softening applies in receive and oblige, all non-derived environments.

The situation is less clear for Halle and Mohanan's Strata 3 and 4. If these levels were cyclic, they could hardly be merged with Stratum 2 to give a single postcyclic level like that suggested by Booij and Rubach (1987). Halle and Mohanan do state that `stratum 2, unlike strata 1 and 3, is a non-cyclic stratum' (1985: 96); however, they produce no arguments for the cyclicity of Stratum 3, and do not even broach the subject with regard to Stratum 4. The only reason for assuming that they regard Strata 3 and 4 as cyclic is their remark that `given that at least some strata have to be cyclic, the null hypothesis would be that all lexical strata in all languages are cyclic' (1985: 67); thus, evidence must be produced to establish the non-cyclic nature of a stratum, but not to establish that it is cyclic. Cyclicity is the default value for lexical strata.

In fact, however, there are good reasons to assume that neither Stratum 3 nor Stratum 4 is cyclic. Whereas a large number of English phonological rules seem to apply on Levels 1 and 2 (see Halle and Mohanan 1985: 100), Halle and Mohanan order only one rule, /l/ Resyllabification, on Level 4, and only two, Stem-Final Tensing (Dialect C) and Stem-Final Lengthening (Dialect B) on Level 3. Mohanan (1986) additionally argues for Sonorant Resyllabification on Level 4. There is certainly no evidence for cyclic application of /l/-Resyllabification, and an analogue of Stem-Final Tensing, Vowel Tensing, applies on non-cyclic Level 2 in Halle and Mohanan's Dialects A and B, without the discrepancies in operation that might be expected due to cyclic application in some dialects and non-cyclic operation in others. In addition, Stem-Final Tensing violates the SCC, which Halle and Mohanan regard as a constraint on all cyclic strata, by applying in city, happy, which are underived and will have undergone no previous processes on the same cycle as the Tensing rule. The same reasoning holds for Stem-Final Lengthening: if Stem-Final Tensing, which feeds the Lengthening rule, were cyclic, then it could create derived environments on the same cycle as Lengthening, which could then apply in city, happy. However, we have already established that Tensing is non-cyclic, so that it may not apply on Stratum 3 if this is a cyclic level. In that case, Stem-Final Lengthening also violates SCC, and consequently cannot be cyclic. If Levels 3 and 4 are indeed non-cyclic, this removes one argument against the incorporation of Halle and Mohanan's Strata 2±4 into a single postcyclic stratum.

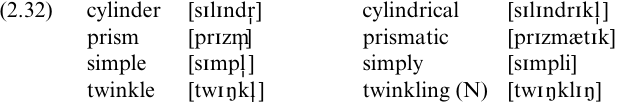

However, the rules Halle and Mohanan (1985) order on Levels 3 and 4 might still necessitate a separation of Strata 2, 3 and 4, all non-cyclic, if they are to apply correctly. I shall now examine this possibility, beginning with Sonorant Resyllabification (2.32), the sole phonological occupant of Halle and Mohanan's Level 4.

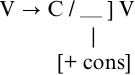

The generalization behind (2.32) is that `In all dialects of English, a syllabic consonant becomes nonsyllabic when followed by a vowel-initial derivational suffix, whether it is class 1 or class 2' (Mohanan 1986: 32). However, sonorants are not resyllabified across the stems of compounds: a syllabic /l/ surfaces in double edged. Mohanan therefore proposes that Stratum 3 (compounding) should be distinguished from Stratum 2 (Class II derivation), and that syllable formation should not reapply at Stratum 3. However, sonorants may resyllabify before vowel-initial inflectional suffixes, giving doubling as [dΛblɪŋ] or [dΛbỊɪŋ], and twinkling as [twɪŋklɪŋ] or [twɪŋkỊɪŋ]. Stratum 4 (regular inflection) must therefore be kept separate from Stratum 3 (compounding). Mohanan cannot account for this resyllabification by invoking the syllable formation rules, since these are inapplicable at Stratum 3 and `the domain of a rule may not contain nonadjacent strata' (Mohanan 1986: 47), and must therefore introduce another rule, given in (2.33).

(2.33) Sonorant Resyllabification (domain: Stratum 4. Optional)

However, Kiparsky (1985: 134±5, fn.2) discusses the same data, but contends that the syllabification facts involving Class II derivational suffixes and inflections are identical: `hinder#ing, center#ing are trisyllabic (versus disyllabic level 1 hindr+ance, centr+al) to exactly the same extent as noun-forming derivational-ing and as the present participle suffix (John's hindering of NP and he was hindering NP)'.

Kiparsky does admit that speakers may contrast disyllabic crackling `pork fat' with optionally trisyllabic crackle#ing, but holds that `here again the abstract noun and inflectional-ing both work the same way and the disyllabic concrete noun in-ing is probably best regarded as an unproductive level 1 derivative' (1985: 135).

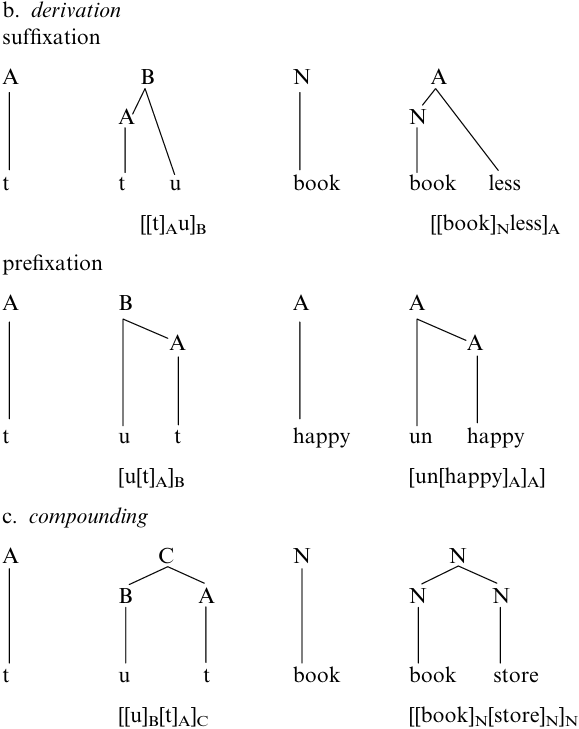

If Sonorant Resyllabification does operate equivalently with Class II derivational affixes and regular inflections, Mohanan's data can be generated in a model of the lexicon with only two strata, and using only one rule. However, this solution depends crucially on the maintenance of a distinction between affixes and stems in terms of brackets, and on the ability of phonological rules to refer to this distinction. Above I simply stated that I would follow Kiparsky (1982), who assumes the structures in (2.34) for affixed forms and compounds.

(2.34) [[ . . . ] .. . ] = stem plus suffix

[ . . . [ ... ]] = prefix plus stem

[[ . . . ][ . . . ]] = compound (stem plus stem)

Kiparsky further assumes that double `back-to-back' brackets, ][, block phonological rules unless they are mentioned in the structural description of the rule, although single brackets do not. I return to this issue below.

In the resulting two-stratum lexicon, compounds, Class II derivation and regular inflection will be ordered on postcyclic Stratum 2, and in terms of brackets, Class II derived items and inflected words will be classed together as against compounds; these alone will contain double internal brackets. If phonological rules are permitted to refer to bracketing configurations, we would expect them to apply to compounds alone, or to all items derived at Stratum 2, or to both types of affixed items, but not to compounds. Sonorant Resyllabification exhibits the last type of behavior. This rule will apply at Stratum 2, but since the double brackets ][ will not be specified in its structural description, it will be unable to operate across the stems of compounds. Sonorant Resyllabification does not, then, require more than a two-stratum lexicon.

The same turns out to be true of /l/-Resyllabification, which moves non-syllabic /l/ from the coda of one syllable into the onset of the next. /l/-Resyllabification and /l/-Velarization, a postlexical rule which `darkens' /l/ in syllable rhymes, together govern the distribution of clear (palatalized) and dark (velarized) variants of /l/ in English. /l/-Resyllabification produces clear [l] in onset position, and thus bleeds /l/-Velarization. Both Halle and Mohanan (1985: 65±6) and Mohanan (1986: 35) state that /l/-Resyllabification operates in compounds and across vowel initial inflections, but not across words. The domain of /l/-Resyllabification must therefore be Stratum 4, in Halle and Mohanan's model.

Neither Halle and Mohanan (1985) nor Mohanan (1986) say whether /l/-Resyllabification applies before vowel-initial derivational suffixes, but informal observations, supported by the data in Bladon and Al-Bamerni (1975), indicate that /l/ is clear in hellish, dealer, scaly. If /l/-Resyllabification does operate in the context of Class II derivational suffixes, the process will be allowed to apply freely to all Level 2-derived forms, and all phonological motivation for Stratum 4 is removed.

The version of /l/-Resyllabification discussed above is not, however, the only one. Mohanan (1986: 35) notes that some British English speakers resyllabify /l/ before any vowel-initial suffix, derivational or inflectional, but not across the stems of compounds or across words, where the /l/ will be dark. Mohanan proposes that speakers of these dialects have a slightly different rule of /l/-Resyllabification, which still applies at Level 4, but which requires the presence of double morphological brackets; given Mohanan's system of bracketing, these double brackets will be present at Stratum 4 in inflected words, but will have been removed medially in compounds by Bracket Erasure at the end of Stratum 3.

However, Mohanan's rule also prevents /l/-Resyllabification from applying before vowel-initial derivational suffixes, since these are attached prior to Stratum 4 in Mohanan's model and their internal brackets will equally have been deleted. Unfortunately, Mohanan (1986: 35) actually says that /l/ is clear for these speakers before vowel-initial derivational suffixes. It is hard to see how this is to be resolved in a four stratum lexicon, without proposing a domain for /l/-Resyllabification consisting of non-adjacent strata.

Nosuch difficulties arise, however, within a two-stratum lexical model, provided that we allow phonological rules to be blocked by morphological bracketing and that compounds are differentiated from affixal formations in terms of bracketing configurations: these requirements were also necessary for the correct application of Sonorant Resyllabification. /l/-Resyllabification will then be a postcyclic, Level 2 rule which will apply in one set of English dialects in all forms derived at Level 2, i.e. in Class II derived, inflected and compound forms. In a second set of (British) English dialects, /l/-Resyllabification will be formulated so as to exploit the difference in morphological structure between derived and inflected forms on one hand and compounds on the other, and will not apply across the double internal brackets of compounds, since these will not be specified in the structural description of the rule.

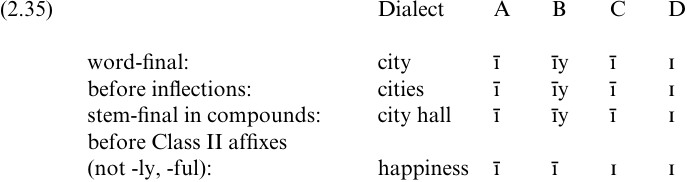

We turn finally to Stem-Final Tensing and Lengthening, which Halle and Mohanan (1985: 59±62) use as evidence for the separation of Levels 2 and 3, and which are intended to account for the treatment of underlying /I/ in four unidentified dialects (see (2.35)).

In Dialect D, stem-final /I/ is never tensed or lengthened. In Dialects A and B, Stem-Final Tensing takes place in all the environments in (2.35); Halle and Mohanan order this rule on Stratum 2 for these dialects. However, /ɪ/ does not tense in Dialect C before Class II derivational suffixes, and [ã Å] in Dialect B does not lengthen, or diphthongize, in this environment. Stem-Final Tensing (Dialect C) and Stem-Final Lengthening (Dialect B) cannot apply on Level 2, since they would then produce *[hæpīnεs] and *[hæpīynεs]. Halle and Mohanan assign these rules instead to Stratum 3, where the appropriate vowel before Class II derivational suffixes will no longer be constituent-final due to Bracket Erasure.

In a two-stratum lexical phonology, non-cyclic Stem-Final Lengthening and Tensing would be ordered on Level 2, and would thus be expected to apply in Class II derived forms, inflected words and compounds; or, if sensitive to bracketing differences, in both sets of affixed forms but not compounds; or in compounds alone. However, there is no way, in terms of brackets, to distinguish compounds and inflected forms from words with Class II derivational suffixes.

Although Halle and Mohanan take this problem as decisive evidence for the necessity of a Stratum 2 versus 3 distinction in English, the difficulty may not be as insurmountable as it seems. Borowsky (1990: 250), for instance, questions the motivation for proposing separate rules of Stem-Final Lengthening and Tensing. She notes that Halle and Mohanan separate these processes because tensed vowels supposedly need not lengthen; thus theses, [θīysīyz], with a long vowel in the final syllable, may contrast with cities, [sɪtīz], in which the second vowel has been tensed but not lengthened. Borowsky attributes this difference instead to `a phonetic difference from the stress' (1990: 251) ± the greater length of the second vowel of theses is due to the fact that this word has two stressed syllables, while cities has only one. Furthermore, Borowsky challenges Halle and Mohanan's assumption that, in their Dialect B, lengthening fails before Class II derivational suffixes, asserting instead that lengthening/tensing will operate in happiness, city, cities and city hall, but that `perceptually the length is more salient in absolute word-final position, or preceding tautosyllabic voiced consonants, as in cities, where weknowthere is an independent phonetic lengthening effect' (1990: 253).

Borowsky also dismisses Halle and Mohanan's contention that the failure of Stem-Final Tensing in happiness in Dialect C necessitates a distinction between Level 2 (Class II derivation) and Level 3 (compounding). She points out that-ly and-ful are already exceptions to their rule, and suggests that `dialect C is one in which a few more of the level 2 affixes block tensing' (1990: 252):-ness at least must be added to the list, although owing to the lack of information in Halle and Mohanan (1985) it is not possible to say whether all Level 2 derivational suffixes behave in this way in Dialect C.

Even if we do not accept Borowsky's reinterpretation, the facts of Stem-Final Tensing and Lengthening are clearly amenable to reanalysis: these two rules then constitute very meagre justification for a stratal distinction, especially one with such far-reaching consequences, since if Halle and Mohanan are right, we must accept that the number of strata in a language cannot be restricted in any principled way, and that cyclic and non-cyclic strata may be interspersed. In addition, Halle and Mohanan's data on Stem-Final Lengthening and Tensing are based only on `an informal survey' (1985: 59); no experimental findings are presented and the four dialects discussed are never identified or localized. It is no wonder that Kaisse and Shaw (1985: 24) regard the rules involved as `probably subject to alternative explanations or indeed to disagreement over the basic facts'.

Finally, Halle and Mohanan's account itself suffers from problems and inconsistencies. First, they assign Stem-Final Tensing (Dialect C) and Stem-Final Lengthening (Dialect B) to Stratum 3, although they consider Stratum 3 to be cyclic, and Stem-Final Lengthening and Tensing both violate SCC. Furthermore, they represent the output of Stem-Final Lengthening in Dialect B as [īy]; however, as a lengthening rule, this process should produce the long monophthong [ii]. The only rule which could then produce [īy] is Diphthongization (Halle and Mohanan 1985: 79), which transforms long uniform vowels into vowel plus offglide structures. However, Halle and Mohanan argue that Diphthongization is a Stratum 2 rule, and since they propose no phonological loop between Levels 2 and 3, it follows that, if Stem-Final Lengthening operates on Level 3, the correct output cannot be derived. If, on the other hand, we assume a two-stratum lexicon, Stem-Final Lengthening can apply on Level 2, feeding Diphthongization (although in fact these rules will be much more radically revised).

It seems, then, that evidence adduced by Halle and Mohanan and Mohanan (1986) for a four-stratum lexical phonology and morphology of English can be refuted, and that the adoption of a two-stratum lexical model (along the lines of Booij and Rubach 1987) can be recommended. However, certain phonological rules in such a revised model will only apply correctly if compounds and affixed forms are differentiated in terms of brackets, and if the phonology is permitted to refer to these morphological distinctions.

Recall that Kiparsky (1982) assumes distinct morphological structures for prefixed forms, suffixed forms and compounds, as shown in (2.34). He also holds that morphological brackets may trigger or block phonological rules. However, Mohanan and Mohanan (1984), Halle and Mohanan (1985) and Mohanan (1986) all disagree with one or both of these assumptions, arguing that compounds and derived or inflected forms are identical in terms of bracketing, or that, even if there are different bracket configurations, phonological rules may not be blocked by them.

Before proceeding to a discussion of the main arguments for and against Kiparsky's position, we should look briefly at the sources of these competing theories of bracketing. In SPE, brackets marking morphosyntactic concatenation were seen as quite separate entities from the phonological boundaries +, # and =, which were units in the segmental string, distinguished from vowels and consonants only by the presence of the specification [- segment] in their distinctive feature matrices. Of the three SPE boundaries, + and # are said to be universal, and are inserted into representations by convention; the formative boundary, +, appears at the beginning and end of each morpheme, while #, the word boundary, borders lexical or higher categories. + and # thus coincide with morphosyntactic brackets. There are also language-specific boundary-weakening processes changing # to +, motivated for instance by inadequacies in the stress rules. The third boundary, =, appears only after the Latinate prefixes de-, per-, con-, inter- and so on, and `is introduced by special rules which are part of the derivational morphology of English' (Chomsky and Halle 1968: 371), again due primarily to wrong predictions made by the stress rules. For instance, Chomsky and Halle represent the verbs advocate and interdict as [ad=voc+ate] and [inter=dict], and modify the Alternating Stress Rule to operate across = when it appears between the second and third syllables from the end of the word, but not when it separates the penultimate and final syllables.

As for the property of blocking and triggering phonological rules, Chomsky and Halle argue that all boundaries may trigger rules, and that + alone typically fails to block them, since any string in the structural description of a process which contains no instances of the formative boundary is taken as a schema for other strings identical but for the presence of any number of occurrences of +. Thus, the cycle in SPE operates within domains bounded by # _ #, disregarding any intervening +. In fact, the formative boundary may block rules, but to achieve this, `we must resort to certain auxiliary devices ... thus adding to the complexity of the grammar' (Chomsky and Halle 1968: 67, fn.10).

The SPE theory of boundaries is clearly quite unconstrained; novel boundaries like = can be introduced on a language-specific basis, and boundaries can be interchanged to forestall problems in the rule system, while no account is taken of the fact that + and # coincide with morphosyntactic concatenation markers. Subsequent developments can be seen largely as attempts to remedy these shortcomings.

Siegel (1974, 1980) reduces the number of permitted boundaries to two, the word and morpheme boundaries. = is replaced by +, on the grounds that `the real generalization governing stress retraction in Latinate prefixed verbs has nothing to do with the boundary with which the prefix is introduced. Rather, it seems to be the case that stress does not retract off stems in verbs where the stem is the final formative' (1974: 117).

Siegel correctly predicts that stress retraction will operate in advocate but not in interdict. She also, as we have seen, proposes a division into Class I, Latinate affixes which may attach to stems or words, affect stress placement, and are introduced with +; and Class II, predominantly Germanic affixes which attach only to words, are stress-neutral (but potentially stress-sensitive) and include # as part of their representation.

Siegel's account involves morphosyntactic brackets as well as phonological boundaries. However, following the introduction of level-ordering by Allen (1978), Strauss (1979) argues against any distinctions among phonological boundaries for English, since the ordering of Class I affixation and the stress rules on Level 1, and of Class II derivation on Level 2, now allows for the different interactions of the two sets of affixes with stress, without reference to word versus morpheme boundary. Strauss equates the single residual boundary with the morphosyntactic bracket. Finally, Strauss accepts Aronoff's (1976) system of bracketing, in which affixes are not independently bracketed, rather than Siegel's, in which affixes and stems are identically delimited by [], on the grounds that, in Aronoff's theory, ```]['' will be unambiguously interpreted as signifying a word-terminal position ... With the richer bracketing possibilities of Siegel's system, ``]['' can be interpreted as a juncture between any two formatives' (Strauss 1979: 395). Here we see the origin of the divergence of the two current bracketing theories, those of Siegel, Halle and Mohanan and Mohanan, versus Aronoff, Strauss and Kiparsky.

Mohanan and Mohanan (1984) accept Kiparsky's proposal that compounds differ from affixed forms morphologically, and that this difference can be encoded using brackets; and they agree that such brackets are preferable to the multiplicity of boundary symbols found in SPE. However, they argue that `morphological brackets may trigger phonological rules, but not block them' (1984: 578): although brackets may be present in the structural description of a rule to cause it to operate, `the effect of boundaries ``blocking'' phonological rules is achieved by stipulating the domain of the relevant rule to be a stratum prior to the morphological concatenation across which the rule is inapplicable' (1984: 598).

Mohanan and Mohanan present no evidence or arguments for this assertion that morphological bracketing is only partially accessible to the phonology, and the same is true of Halle and Mohanan (1985). Halle and Mohanan do not distinguish compounds from affixed forms, proposing the structure [[ ... ][ ... ]] for both, but their only justification for dropping Kiparsky's distinction is that they `see no reason to distinguish between compounding and affixation in terms of bracketing' (1985: 60). Halle and Mohanan's separation of Strata 2, 3 and 4 for English is a reminder that they do indeed see reason for such a distinction, albeit differently encoded.

Mohanan (1986), who, like Halle and Mohanan, uses the same bracketing for compounds and derived or inflected forms, provides the only real arguments against Kiparsky's and Strauss's proposal; but even these are not strong. Mohanan's arguments are intended to support two stipulations: first, he asserts that `morphological brackets are incapable of blocking rules' (1986: 20) and secondly, that `if a grammar has to distinguish between compounding and affixation, it may do so by making a stratal distinction, but not by making a distinction in terms of brackets' (1986: 128).

Mohanan's first two arguments are that a theory which does not distinguish X]Y from X][Y is more restrictive than one which does, and that, even given such a distinction, a theory allowing brackets to block phonological rules is less restrictive than one which disallows this. However, we have already seen that a two-stratum model of the lexicon, with only one cyclic and one postcyclic level, has various advantages over Mohanan's four-level model. If Mohanan is correct, we must accept that a theory allowing, in principle, an infinite number of lexical strata with cyclic and non-cyclic strata arbitrarily interspersed is more restrictive than one which permits only two lexical levels, but allows the phonology to make reference to independently necessary morphological brackets.

Mohanan's contention that brackets may not block phonological rules can be traced back to the SPE distinction of the non-blocking formative boundary from other boundaries, which could both trigger and block rules. Like Chomsky and Halle, Mohanan does not deny that boundaries may appear to block rules, but chooses to encode this blocking via stratification rather than allowing phonological processes to make direct reference to morphosyntactic brackets. The fact that Mohanan allows brackets to trigger but not block rules in this way is merely a stipulation which in no way follows from the tenets of the theory; this is amply demonstrated by the existence of a completely opposing situation in Natural Generative Phonology, where Hooper (1976: 15) asserts that non-phonological boundaries like the word and morpheme boundaries may block rules but not condition them. Mohanan (1986: 143) attempts a justification, claiming that `saying that the presence of brackets, which represent the concatenation and hierarchical structure of forms, can block phonological rules ... is as conceptually incoherent as saying that the presence of features like [+ noun] can block the application of phonological rules unless mentioned by the structural description'. But this objection can also be countered, for two reasons. First, why should the presence of morphological brackets in a phonological rule be admissible if they are to trigger it, but `conceptually incoherent' if they are to stop it? Secondly, it is clear that phonological rules must be able to refer to some kinds of morphological information - indeed, one of Mohanan's own criteria for the separation of lexical and postlexical rules is that lexical rules require access to such morphological information, while postlexical operations never do - and again it seems inexplicable that a phonological rule can be sensitive (as Halle and Mohanan's Velar Softening rule is) to the presence of a feature like [+ Latinate], which refers to an etymologically motivated division of the vocabulary peculiar to English, but not to morphological brackets, which encode a putatively universal distinction of stems from affixes.

Mohanan (1986: 21) points out that, given his stipulation that blocking involves ordering on an earlier level, it is impossible for Level 1 morpheme boundaries to block rules, capturing the SPE generalization that the behavior of + is different from that of other boundaries. However, Mohanan does not recognize separate boundaries like the + and # of SPE, but only morphosyntactic brackets, which are of the form ] and [ on all levels. He is then forced into the general statement that brackets may not block phonological rules, in effect making all brackets exceptional to accord with the exceptionality of brackets on Level 1.

It seems preferable to say that phonological rules may refer to morphological bracketing, which may either condition or block them at all levels of the lexicon, but with the proviso that Level 1 bracketing in English does not block rules. The effect of such blocking is actually achieved by the cyclic nature of Stratum 1 and the operation of the SCC, which in my model, like that of Booij and Rubach (1987), will be restricted to the earliest lexical level. This insight, however, is lost in Mohanan's framework, since he allows cyclic and non-cyclic strata to be randomly interspersed, and does not regard Level 1 as the sole cyclic level. At the moment, we have insufficient cross-linguistic data to verify that Level 1 brackets universally fail to block rules; this may relate to the putative universality of Booij and Rubach's model, which similarly is yet to be ascertained.

We return now to the question of whether prefixation, suffixation and compounding should be differentiated, as Kiparsky and Strauss advocate, or whether the representation [[ ... ][ ... ]] should be adopted for both affixation and compounding, as suggested by Halle and Mohanan (1985) and Mohanan (1986). Mohanan's argument here is that bracket notation encodes constituent structure, incorporating information on order of concatenation, linearity and categories: bracketing therefore corresponds to tree-diagram notation. Mohanan then notes that representations like [[[X]Y]Z] or [[X[Y]]Z] have no tree-structure counterparts, and argues that this `means either that brackets are not a notational equivalent of trees, or that the representations ... are illegitimate' (1986: 129). Since Mohanan is committed to the equivalence of brackets and trees, he must draw the second conclusion; and since the potentially illegitimate representations match Kiparsky's notation for a stem with two suffixes (e.g. hopelessness) and a stem with one prefix and one suffix (e.g. unsafeness) respectively, Kiparsky's bracketing system must be abandoned if Mohanan's argument holds.

However, Mohanan's case rests on the assertion that Kiparsky's bracketing configurations have no tree-diagram equivalents; the pro vision of just such hierarchical representations by Strauss (1982) consequently robs it of much of its force. Strauss proposes representations like a., b. and c., in (2.36) below as the tree and bracket configurations corresponding to inflection, derivation and compounding respectively.

If these correspondences are accepted, Kiparsky's bracketings [[[X]Y]Z] (hopelessness) and [[X[Y]]Z] (unsafeness), which Mohanan claimed cannot be assigned tree-diagram counterparts, can be paired with the hierarchical structures in (2.37).

Mohanan acknowledges that these trees would provide the morphological distinctions necessary to delimit the lexical phonology to two levels, at least for English. However, he objects to Strauss's model, Lexicalist Phonology, and to his introduction of inflectional representations entirely lacking internal bracketing. The first objection is irrelevant here, as Strauss's hierarchical representations can be accepted in isolation from his framework. The second seems more justifiable. Strauss proposes bracketings like [book s] for books, to indicate both that-s is a bound element, like all derivational and inflectional affixes, and that it does not cause a category change; in Strauss's view, additional external brackets serve only to show a categorial reassignment. However, his representation loses the generalization that stems and words, like book in this case, are always autonomously bracketed, and makes it necessary for him to include the symbol +, giving [book + s], simply to show that two formatives are present.

I propose that inflection and derivation should instead be represented equivalently, as b. in (2.36) above, and that the category-changing versus category-maintaining parameter should be regarded as less significant, since it is not the case that all derivational affixation entails an alteration of category; for instance, prefixation of un- to an adjective produces a (negative) adjective. The resulting tree and bracket notations, which are equivalent to those of Kiparsky (1982), are given in (2.38) below.

If this is not yet sufficiently conclusive, further evidence against Mohanan's representations of both compounding and affixation as [[ . . . ][ . . . ]] comes from Selkirk (1982a). Selkirk uses Kiparsky's system of bracketing, although she denies direct access of phonological rules to such brackets. Instead, affixes are marked with the special category label Af, while stems and words receive a lexical category symbol such as N, V or A. However, Selkirk's arguments equally support a theory which does permit the morphological concatenation operators to block and condition rules.

Selkirk argues that, for two main reasons, affixes and stems/words, and hence affixed items and compounds, must be differentiated in morphological structure, either using brackets and category labels, or brackets alone. First, she asserts that `compound words do not have the same phonology as affixed words' (1982a: 123), a contention supported for English in respect of the rules, as well as the stress rules. Such rules, which `apply to, or interpret, morphological structures ... must ``know'' whether a morpheme is an affix or not'; and clearly, this difference can be encoded via bracketing.

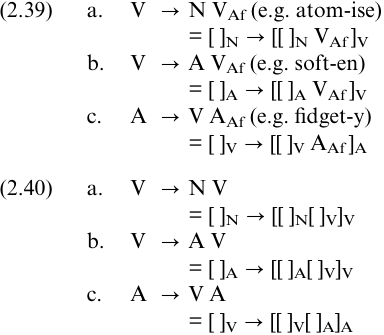

Secondly, Selkirk (1982a: 123) argues that, if compounding and derivational affixation involved fundamentally the same word-formation process, `the word-structure rules required for generating affixed words would be the same as those generating compound words'. For derivationally affixed forms, Selkirk proposes the rules shown in (2.39). In Mohanan's model, where affixes are effectively regarded as stems/words, these would have to be replaced by the rules in (2.40), to accord with those for compounding: but actual compounds of the form generable by the rules in (2.40) do not exist in English.

Finally, Mohanan's morphological organization follows Lieber (1981), who assumes that affixes are lexically stored with major word class categories, and are the heads of words, so that these categories will be transferred to the eventual word by feature percolation. However, Miller (1985) and Corbett, Fraser and McGlashan (1993) argue that the concept of head does not generalize easily from syntax to morphology, while Zwicky (1985) defends the traditional viewpoint of stems as major elements and affixes as minor markers of insertion rules, arguing that `the apparently determinant formative in affixal derivation is merely a concomitant of the operation' (1985: 25). Lieber's system also arguably belongs to the Item-and-Arrangement school of morphology (Hockett 1954), and is therefore subject to the familiar criticisms of this model reiterated in Matthews (1974) and Miller (1985). For instance, feature percolation can cope reasonably well with linear, agglutinative operations, but Lieber is forced to introduce further powerful mechanisms in the form of string-dependent lexical transformations to deal with reduplication and other non-concatenative processes of word-formation; see Bauer (1990) for further limitations of percolation. Giegerich (in press) adopts a position intermediate between Mohanan and Kiparsky here, arguing that stems and affixes are lexically stored; that affixation on Level 2 is achieved by Kiparsky-type rules, but on Level 1 by listing; but that roots, prefixes and suffixes are crucially distinguished by bracketing. This has some repercussions for the constraints of LP, to be discussed later, but does not challenge my adoption of Kiparsky's bracketing representations, or the assumption that brackets may block and condition phonological rules. A two-stratum model of the lexicon, incorporating these assumptions.

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة