Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Phonology

المؤلف:

APRIL McMAHON

المصدر:

LEXICAL PHONOLOGY AND THE HISTORY OF ENGLISH

الجزء والصفحة:

42-2

2024-11-26

949

Phonology

The organization of the morphological component of the lexicon assumed in LP should now be clear. However, the morphology is not the sole inhabitant of the lexicon; rather, there is considerable interaction with the phonology.

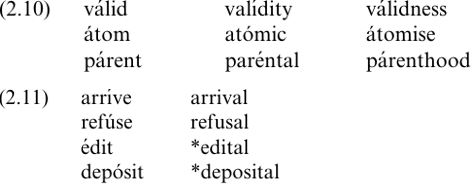

Siegel (1974) did not motivate her division of English derivational affixes into Classes I and II solely by reference to morphological factors, but adduced additional evidence from their phonological behavior. In particular, Siegel notes that Class I suffixes shift the stress of the stem, while Class II affixes are stress-neutral (2.10). However, Class II affixes may have constraints on their insertion, governed by the position of stress on the stem; thus,-alN attaches only to verbs with final stress. Such constraints do not affect Class I affixes (2.11).

Siegel consequently proposes that cyclic phonological rules, including word-stress assignment, should operate between Class I and Class II affixation in the lexicon; Class I affixes will then be added before stress-placement, so that the position of stress on an underived base and on a Class I affixed form may be calculated differently by the stress rules. Class II affixation will occur too late to influence stress assignment, but may be sensitive to the already determined position of stress.

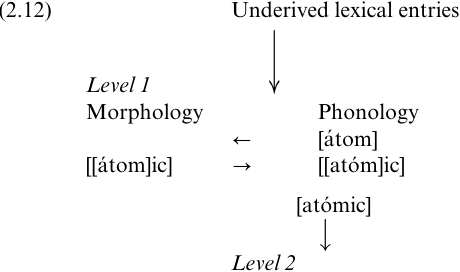

Allen (1978) observes that this interaction of morphology and phonology is not limited to the stress rules, and suggests that on each stratum a particular boundary will be assigned to structures derived on that stratum: the boundary will be + on Level 1, and # on Level 2. Phonological rules may then be formulated to apply across + but not #. Subsequently, Mohanan (1982) and Kiparsky (1982) translate these preliminary observations into a much more integrative model. The central assumption of LP is that each lexical level constitutes the domain of application for a subset of the phonological rules, as well as certain word-formation processes. The phonological rules do not apply between the morphological strata, as Siegel suggested, but are assigned to them. The output of every morphological operation is passed back through the phonological rules on that level; this builds cyclicity into the model, and allows for the progressive and parallel erection of phonological and morphological structure, as shown in (2.12).

This model also removes the need for distinct boundary symbols such as + and #. Instead, the distinct boundaries of SPE are replaced by a single bracket, `which is actually nothing more than the concatenation operator on both the morphological and syntactic levels' (Strauss 1979: 394), and their effects are captured by level ordering.

We can now turn to the second major input to LP, the abstractness controversy, perhaps best introduced with reference to Kiparsky's (1982) account of Trisyllabic Laxing (TSL) in English.

TSL (2.13) laxes (or shortens) any vowel followed by at least two vowels, the first of which must be unstressed.

(2.13) V → [ - tense] / - C0ViC0Vj

where Vj is not metrically strong

(Kiparsky 1982: 35)

declare ~ declarative divine ~ divinity table ~ tabulate

TSL was problematic for the SGP model because of the presence of the two classes of exceptions exemplified in (2.14).

(2.14) a. mightily bravery weariness

b. ivory nightingale Oberon Oedipus

In LP terms, the first set of exceptions all include Class II suffixes, while the forms undergoing TSL in (2.13) all have Class I affixes; thus, we simply order TSL on Level 1. The forms in (2.14a) will only become trisyllabic on Level 2, beyond the domain of TSL. The exceptions in (2.14b) are more problematic. The SGP methodology would involve adjusting the underlying representations of forms like nightingale, ivory so that the structural description of TSL is not met. For instance, Chomsky and Halle assigned nightingale the underlying form /nɪxtVngæl/; further rules were then required to transform /ɪx/ into surface [aɪ]. However, this stratagem promotes abstractness, and is ad hoc, non-generalizable, and non-explanatory.

Kiparsky also notes the existence of a further problematic set of words (2.15), which `have two possible derivations, while only one is ever needed' (1982: 35).

(2.15) camera pelican enemy

These words could be derived from underlying representations with a short, lax vowel in the first syllable, but the more likely SGP derivation would involve positing underlyingly long, tense vowels, and giving these non-alternating forms a `free ride' through the TSL rule. The drive for maximal generality of rules, and the attendant principle that surface irregularity should stem from underlying regularity, thus add considerably to the abstractness of the model.

Kiparsky claims that, within LP, a single constraint can explain the non-application of TSL in the forms in (2.14b), and prohibit the derivation of the words in (2.15) from remote underliers. Kiparsky refers to work on the strict cycle in phonology (Kean 1974, Mascaró 1976, Rubach 1984), where it is claimed that cyclic rules are only permitted to apply in derived environments. The Strict Cyclicity Condition (SCC), which effects this restriction, is formulated in (2.16).

(2.16) SCC: Cyclic rules apply in derived environments. An environment is derived for rule A in cycle (i) iff the structural description of rule A is met due to a concatenation of morphemes at cycle (i) or the operation of a phonological rule feeding rule A on cycle (i).

TSL, as a cyclic rule subject to SCC, will be permitted to apply in declarative, divinity, etc. due to the prior application of a Level 1 affixation rule on the same cycle. However, it will not be applicable in ivory and nightingale; these happen to meet the structural description of TSL at the underlying level, but they are not trisyllabic by virtue of any concatenation operation, nor do they undergo any phonological rule feeding TSL. Their underliers can therefore be listed as equivalent to their surface forms, and their apparent exceptionality with respect to TSLfollows automatically from the SCC.

Likewise, the mere assignment of a tense vowel to the first syllable of forms like pelican, enemy and camera will no longer enable these to be passed through TSL, since they will constitute underived environments for the laxing rule: the appropriate surface form [εnəmi] is no longer derivable from [ēnεmɪ], if we assume the validity of SCC and accept that TSLis a cyclic rule.

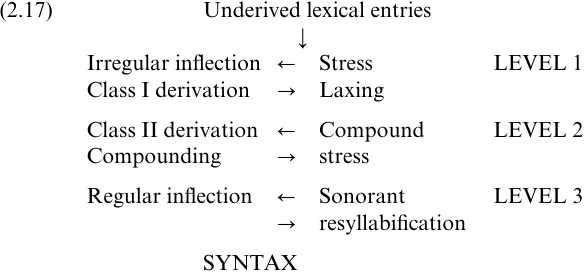

In the earliest versions of LP (Mohanan 1982, Kiparsky 1982) it was assumed that all lexical rules were cyclic, as shown in the model for English given in (2.17) (adapted from Kiparsky 1982: 5).

In such a model, the domain of SCC would be the entire lexicon, and all lexical phonological rules would be restricted to derived environments. This early, strong claim has been somewhat weakened since, so that it is now generally accepted that not all cyclic rules are subject to SCC, and that not all lexical rules are cyclic.

First, it appears that rules which build structure rather than changing it should not be subject to SCC (Kaisse and Shaw 1985), to allow stress rules, and syllabification rules erecting metrical structure, to apply on the first cycle in underived environments. Stems like atom will then be eligible for stress assignment and syllabification without undergoing previous morphological or phonological processes. Kiparsky (1985) further suggests that an initial application of a structure-building rule should not be accepted as creating a derived environment for a subsequent structure changing rule.

Secondly, Halle and Mohanan (1985) claim that there are a number of phonological rules which, due to their interaction with morphological processes and other rules of the lexical phonology, should themselves apply in the lexicon, but which do not obey SCC. For instance, Velar Softening is clearly sensitive to morphological information, since it applies in Class II derived forms like magi[ʃ]ian, but not medially in compounds, as in magi[k] eye. Since Velar Softening must be ordered before Level 2 Palatalization, Halle and Mohanan argue that it should also apply on Level 2. However, Velar Softening also applies in un derived forms like reduce and oblige, although this should be prohibited by the SCC if Velar Softening is a cyclic rule. Halle and Mohanan produce similar arguments for a number of the core rules of English vowel phonology, including the Vowel Shift Rule; again, they propose that Vowel Shift should be ordered on Level 2 of the lexicon, but again this rule is said to apply, in apparent contravention of SCC, in underived forms like divine, sane and verbose.

These findings have provoked various limitations of the power of SCC. Kiparsky (1985) suggests that rules on the last lexical level are exempt from SCC, although he does not explicitly state whether he believes rules on this `word level' to be cyclic or non-cyclic. A far more radical solution is adopted by Halle and Mohanan (1985) and Mohanan (1986), who argue that `the cyclicity of rule application in Lexical Phonology ... is a stipulation on the stratum' (Halle and Mohanan 1985: 66); thus, cyclic and non-cyclic strata may be interspersed. Mohanan (1986: 47) even proposes that all lexical strata are non-cyclic in the unmarked case, reversing Kiparsky's earlier hypothesis on the relationship between cyclicity and lexical application. reversing Kiparsky's earlier hypothesis on the relationship between cyclicity and lexical application.

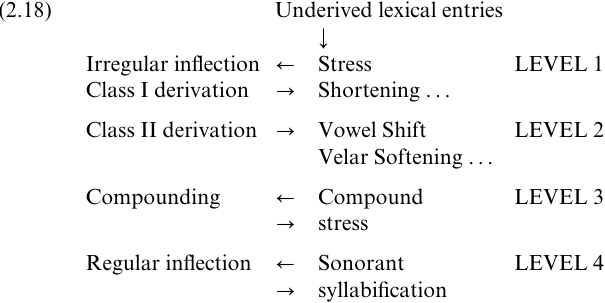

The lexical structure which Halle and Mohanan (1985) propose for English is shown in (2.18). There are four lexical levels; three are cyclic, but Level 2, the domain of Velar Softening and the Vowel Shift Rule, is non-cyclic. On cyclic strata, forms pass through the phonology, then to the morphology, and are resubmitted to the phonology after every morphological operation. On non-cyclic strata, however, all appropriate morphological rules apply first, and the derived form then passes through the phonological rules on that level once only.

The matter of the number of cyclic and non-cyclic strata is inextricably linked with the problem of limiting the overall number of strata. Kiparsky, as we have seen, proposed three levels for English; Halle and Mohanan (1985) argue for four. The lack of any principled limitation on the number of lexical levels proposed has cast serious doubts on the validity of LP; it would be theoretically possible, for instance, to propose a level for every rule, or some arbitrary number of levels with all rules applying on all levels. Even if individual analysts refrain from positing unrealistically high numbers of levels, the potential for unconstrained stratification remains, making a lexicalist model potentially unconstrain able; and in any case, we have no criteria to tell us what number of strata would be unrealistically high.

Recent emendations to LP by Booij and Rubach (1987) aim to provide a universal lexical organization, a constrained number of strata, and a principled division of cyclic from non-cyclic levels. On the basis of evidence from Dutch, Polish, French and English (admittedly a restricted corpus), Booij and Rubach restrict the lexical component to one cyclic and one postcyclic level. This model, applied to English, gives the lexical organization shown in (2.19). I shall simply accept this restrictive model for the moment.

Finally, not all phonological rules in LP are lexical; some apply in a post-lexical component, located after the syntax. If the lexical phonology corresponds roughly to the morphophonemic rules of SGP, the post lexical rules may be thought of as allophonic, an equation supported by the strong similarity of the `lexical level' of representation, the output of the lexicon, to the classical phonemic level. The two types of rules are characterized by different syndromes of properties, which can be used to determine the component in which a given rule applies. For instance, there are considerations of ordering: if a rule necessarily applies before a rule which must, for independent reasons, be lexical, then it must itself be lexical. Similarly, a process which crucially follows a postlexical rule will be postlexical. If a rule can be shown to be cyclic, it must also be lexical; more specifically, in Booij and Rubach's (1987) model, it must apply on Level 1. Further evidence must, however, be adduced to decide whether a non-cyclic rule is postcyclic or postlexical. For instance, any rule which is conditioned or blocked by the presence of brackets, exception features, or morphological features such as [± Latinate] in the string, is necessarily lexical. The expected sensitivity of lexical phonological rules to word internal structure follows from their interaction with the morphology, while the opacity of such internal structure for postlexical processes is a natural result of bracket erasure at the end of each level. Conversely, it follows from ordering with respect to syntactic concatenation that only postlexical phonological rules may apply across word boundaries.

Lexical rules may also have lexically marked exceptions, but post-lexical ones apply wherever their structural description is met. Bresnan (1982) similarly argues that only lexical syntactic rules may have exceptions; perhaps the correlation of lexical application with exceptionality reflects the early transformational-generative characterization of the lexicon as a store of idiosyncratic information. Furthermore, it was the irregular, exceptional tendencies of derivational morphology which prompted Chomsky (1970) to move it into the lexicon, initiating the lexical expansion which has led to LP. Finally, postlexical rules may create novel segments and structures, but lexical rules are structure preserving, and may not create any structure which is not part of the underlying inventory of the language. I give Borowsky's (1990: 29) definition of Structure Preservation in (2.20).

(2.20) Structure Preservation: Lexical rules may not mark features which are non-distinctive, nor create structures which do not conform to the basic prosodic templates of the language.

Structure Preservation (SP) is the third major constraint of LP, after the EC and the SCC and, like the other two, is rather controversial. I shall return to it below.

Mohanan (1986) regards the postlexical component as bipartite. He suggests that forms exit the lexicon and enter first a syntactic submodule, including phonological rules which make necessary reference to syntactic information, such as the rule governing the a ~ an alternation in English. This submodule creates a syntactico-phonological representation of phonological phrases; these then pass into a postsyntactic submodule, where phonetic implementation rules `spell out the details of the phonetic implementation of a phonological representation in terms of gradient operations' (Mohanan 1986: 151). In other words, Mohanan, like Chomsky and Halle (1968), argues that binary features become scalar late in the derivation, although again like Chomsky and Halle, he gives no details of how this transition is to be achieved. For instance, Mohanan notes that the degree of aspiration of voiceless stops in English depends on the degree of stress, so that scalar values are required in the phonetic implementation submodule. Mohanan emphasises that these implementational rules are not universal and purely physiological, but low-level and language-specific; for instance, the dependence of aspiration on stress does not hold in Hindi or Malayalam.

Mohanan further argues that `mappings in the implementational module may dissolve phonological segments' (1986: 173). At the eventual phonetic level, the derivation will then produce features which are assigned scalar values and aligned independently with a timer. The potential for overlap which this alignment provides seems promising for the treatment of coarticulation and timing; we shall return to this issue, from a rather different angle.

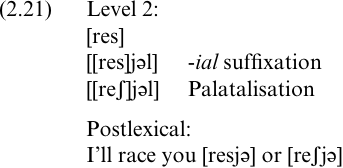

Finally, rules may apply both lexically and postlexically: for instance, Palatalization in English (2.21) must, for reasons of ordering and interaction with the morphology, apply on Level 2 of the lexicon, but it also operates between words.

Kiparsky (1985) extends this notion of application in two components, proposing that a process which appears to apply in a gradient fashion may be a postlexical reflex of a rule which also applies categorically in the lexicon.

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)