REDUCING UNCERTAINTY WITH MODIFIERS

المؤلف:

CHARLES E. OSGOOD

المؤلف:

CHARLES E. OSGOOD

المصدر:

Semantics AN INTERDISCIPLINARY READER IN PHILOSOPHY, LINGUISTICS AND PSYCHOLOGY

المصدر:

Semantics AN INTERDISCIPLINARY READER IN PHILOSOPHY, LINGUISTICS AND PSYCHOLOGY

الجزء والصفحة:

512-28

الجزء والصفحة:

512-28

2024-08-22

2024-08-22

1206

1206

REDUCING UNCERTAINTY WITH MODIFIERS

Usage of adjectives and adverbs clearly reflects presuppositions on the part of the speaker as to the amount of information possessed by the listener about the entity being referred to. (1) If the entity is presumed to be novel to the listener, and hence must be identified (‘established’ as a referent according to Sampson, 1969), the speaker is under pressure to elaborate the noun phrase; if it is presumed to be familiar already, and hence need merely be recognized (‘ re-identified ’ according to Sampson) by the listener, economy dictates stripping the noun phrase to the bare nominal bone.1 (2) If the entity is a member of a set, to all of which a selected noun applies, and if either (a) the intended entity must be distinguished from others previously identified (implicit contrast over time) or (b) the intended entity must be distinguished from others presently being identified (explicit contemporary contrast), then the speaker is under pressure to use distinguishing modifiers to reduce the listener’s uncertainty.2 These contrastive conditions for modifying noun phrases are well described by Olson (1969) in what he calls the ‘paradigm case’ - a gold star being placed under the same ROUND WHITE WOODEN BLOCK, but the observer describing this simple event as under the white one (if a ROUND BLACK BLOCK is also present), under the round white one (if both ROUND BLACK and SQUARE WHITE are present), and so forth.3

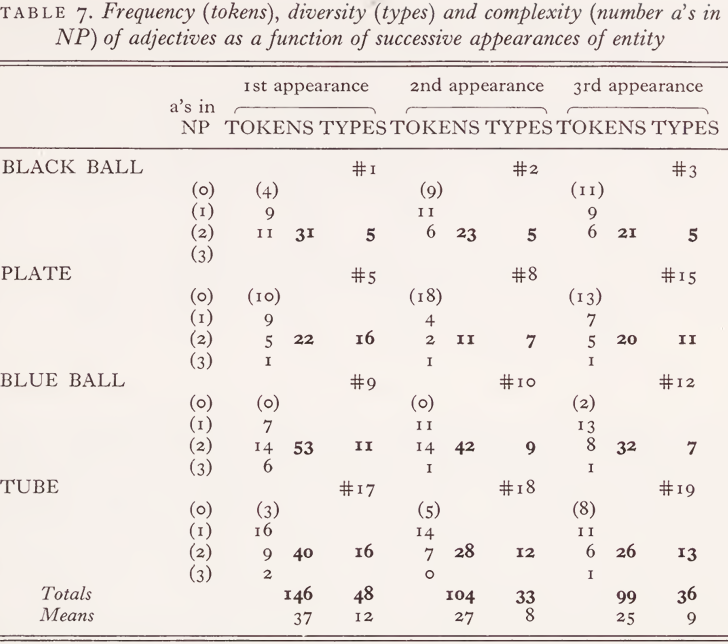

These two functions of modifiers - identifying vs. distinguishing - cross-cut the functions of Indefinite and Definite determiners and pronouns. The identifying function parallels the use of indefinite a. Table 7 presents both the number of adjective tokens (totals) and the number of adjective types (different adjectives) for the same reappearing entities as reported in Table 5 for determiners (BLACK BALL, PLATE, BLUE BALL and TUBE), in terms of both order of appearance (columns) and complexity of noun phrases (rows) - the latter being (o), only noun, and (1), (2) or even (3) modifying levels are in bold-face type. First we note, again, that the big drop in frequency and diversity of qualifying is between first and subsequent appearances, which is the clearest separation between ‘ identifying ’ and ‘ recognizing ’. Also, again, when there is a big time gap between successive appearances (e.g., PLATE for second, event #8, and third, event #15) the tendency to ‘identify’ reasserts itself, suggesting that this is a continuous semantic feature. Secondly, it can be seen that, very consistently for successive appearances, the complexity of noun phrases referring to the entities decreases; for example, for BLUE BALL there are 6 triple adjectives, 14 double and only 7 single for the first appearance, whereas by the third there is only one triple, 8 doubles and 13 single adjectives. (In all cases of single adjective, it was blue.) Quite evidently, as the speaker presupposes more familiarity with the referent, the less the frequency, diversity and complexity of his adumbrations on the head noun.

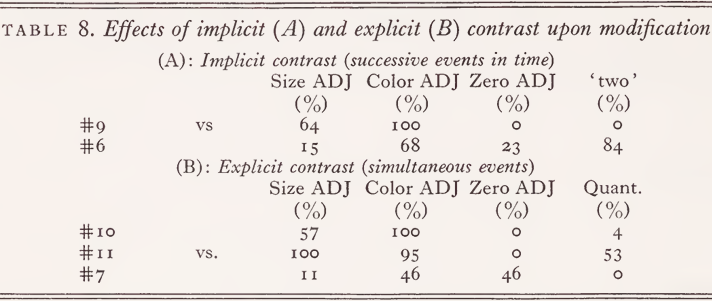

Conversely - and independent of whether the intended referent is being identified (novel) or being recognized (familiar) - if the perceptual entity must be contrasted with others of its class, then we find an increased likelihood of adjectival modification. Table 8(A) provides a demonstration of the effects of implicit contrast, comparing # 9 (THE MAN IS HOLDING A BLUE BALL), with # 6 (THE MAN IS HOLDING TWO BALLS) ; the sudden contrast of a larger blue ball with only small black balls which had preceded this event creates a very high frequency of both color and size adjectives, as compared with #6, and no sentences without adjectives. I have added to this table the effects of TWO BLACK BALLS upon producing sentences with two #6, just to hammer in the obvious. Table 8(B) provides a parallel demonstration of the effects of explicit contrast, comparing #10 (A BLACK BALL ROLLS AND HITS THE BLUE BALL) and #11 (A BIG ORANGE BALL IS HIT BY A BLACK BALL) with #7 (ONE BALL ROLLS AND HITS THE OTHER); the simultaneous perceptual presence of two balls constrastive in both size and color produces the predicted adjectival effects, and there are no sentences without adjectives as compared with 46% zero ADJ in #7. Here I add the frequency of quantifiers: the sudden appearance of the orange ball (over double the size of the blue ball) for the first time in # 11 produced 53 % sentences with much and very; the one observer of #10 who quantified wrote medium blue ball, and no one used a quantifier for #7.

Manner adverbs serve the same identifying and contrasting functions for perceived actions as adjectives do for perceived entities. When an action deviates from an implicit norm (contrastive over past experience) and thereby contradicts a presupposition about that kind of action, the probability of adverbial modification increases. No deliberate test of this proposition was made, but it could easily be demonstrated, e.g., by THE MAN REACHING WITH EXCRUCIATING SLOWNESS FOR A BALL. However, when an action deviates from a standard established in immediately prior perception, adverbial modification is also predicted. Demonstration #3 (THE BALL IS ROLLING ON THE TABLE) produced only 8% adverbials (both sentences containing quickly) and no other ‘manner’ expressions, but the immediately following #4 (THE BALL IS ROLLING SLOWLY ON THE TABLE) produced 68 % slowly and 11 % other ‘manner’ expressions.

1 Sampson relates ‘establishing’ and ‘re-identifying’ to both selection of indefinite vs. definite articles and to usage of pronouns, but he does not extend these same cognitive preconditions to the use of adjectives. That all three aspects of noun phrases are influenced commonly indicates that postulation of such cognitive pre-conditions for their form and content, e.g., where noun phrases come from (cf. McCawley, this volume), is well-motivated, not ad hoc.

2 Of course, the same underlying cognitive conditions can also lead to the selection of a more finely differentiating noun as head of an NP (e.g., husband rather than married man) or verb as head of a VP (meander rather than walk slowly and aimlessly).

3 Apparently because in this paradigmatic case speakers substitute one for wooden block (where all entities are wooden blocks), Olson claims that ‘words do not name things’ (p. 16). Not one of my observers said the man is holding a small black one for demonstration # 1! Surely, by the same general principle of uncertainty reduction which Olson stresses, the use of ball to name (distinguish) this sub-set of palpable objects from many others (blocks, marbles, earrings, etc. and etc.) is equally informative - indeed, rather grandly so, since whole bundles of semantic features are being selected rather than a single feature being discriminated.

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة