Split CP: Force, Topic and Focus projections

Our discussion of wh-movement was concerned with movement of (interrogative, exclamative and relative) wh-expressions to the periphery of clauses (i.e. to a position above TP). However, as examples like (1) below illustrate, it is not simply wh-constituents which undergo movement to the clause periphery:

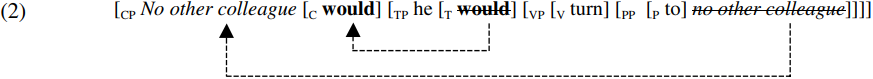

In (1), no other colleague (which is the complement of the preposition to) has been focused/focalised – i.e. moved to the front of the sentence in order to focus it (and thereby give it special emphasis). At first sight, it would appear that the focused object moves into spec-CP and that the pre-subject auxiliary would moves from T to C in the manner shown in (2) below (simplified inter alia by not showing he originating within VP):

However, one problem posed by the CP analysis of focusing/focalization sketched in (2) is that a structure containing a preposed focused constituent can occur after a complementizer like that, as in:

However, one problem posed by the CP analysis of focusing/focalization sketched in (2) is that a structure containing a preposed focused constituent can occur after a complementizer like that, as in:

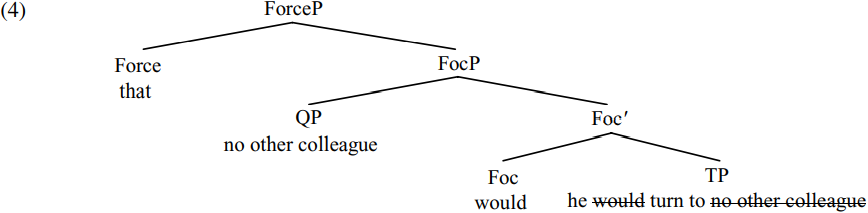

This suggests that there must be more than one type of CP projection ‘above’ TP in clauses: more specifically, there must be one type of projection which hosts preposed focused constituents, and another type of projection which hosts complementizers. Reasoning along these lines, Luigi Rizzi (1997, 2001b, 2003) suggests that CP should be split into a number of different projections – an analysis widely referred to as the split CP hypothesis. More specifically, he suggests that complementizers (by virtue of their role in specifying whether a given clause is declarative, interrogative, imperative, or exclamative in force)should be analyzed as Force markers heading a Force P (= Force Phrase) projection, and that focused constituents should be analyzed as contained within a separate Foc P (= Focus Phrase) headed by a Foc constituent (= Focus marker).

On this view, the bracketed complement clause in (3) would have the structure shown in simplified form below:

The focused QP/quantifier phrase no other colleague originates as the complement of the preposition to and (by virtue of being focused) moves from complement position within PP into specifier position within FocP. The auxiliary would originates in T and from there moves into the head Foc position of FocP. One way of describing the relevant data is to suppose that the head Foc constituent of FocP carries an [EPP] feature and an uninterpretable focus feature which together attract the focused object no other colleague (which itself contains a matching interpretable focus feature) to move into spec-FocP, and that Foc is a strong head carrying an affixal [TNS] feature which attracts the auxiliary would to move from T into Foc.

The focused QP/quantifier phrase no other colleague originates as the complement of the preposition to and (by virtue of being focused) moves from complement position within PP into specifier position within FocP. The auxiliary would originates in T and from there moves into the head Foc position of FocP. One way of describing the relevant data is to suppose that the head Foc constituent of FocP carries an [EPP] feature and an uninterpretable focus feature which together attract the focused object no other colleague (which itself contains a matching interpretable focus feature) to move into spec-FocP, and that Foc is a strong head carrying an affixal [TNS] feature which attracts the auxiliary would to move from T into Foc.

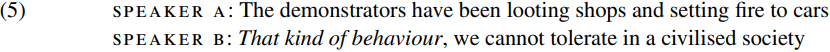

From a discourse perspective, a focused constituent typically represents new information (i.e. information not previously mentioned in the discourse and assumed to be unfamiliar to the hearer). In this respect, focused constituents differ from another class of preposed expressions which serve as the topic of the clause immediately containing them. Topics typically represent old information (i.e. information which has already been mentioned in the discourse and hence is assumed to be known to the hearer). In this connection, consider the sentence produced by speaker B below:

Here, the italicized phrase that kind of behavior refers back to the activity of looting shops and setting fire to cars mentioned earlier by speaker A, and so is the topic of the discourse. Since the topic that kind of behavior is the complement of the verb tolerate it would be expected to occupy the canonical complement position following tolerate. Instead, it ends up at the front of the overall sentence, and so would seem to have undergone a movement operation of some kind. Since the relevant movement operation serves to mark the preposed constituent as the topic of the sentence, it is widely known as topicalization. (On differences between focusing and topicalization, see Rizzi 1997; Cormack and Smith 2000b; Smith and Cormack 2002; Alexopoulou and Kolliakou 2002; and Drubig 2003.) However, since topicalization moves a maximal projection to a specifier position on the periphery of the clause, it can (like focusing and wh-movement) be regarded a particular instance of the more general A-bar movement operation whereby a moved constituent is attracted into an A-bar specifier position (i.e. the kind of specifier position which can be occupied by arguments and adjuncts alike).

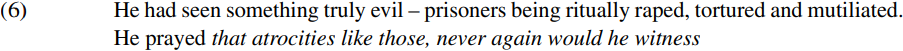

Rizzi (1997) and Haegeman (2000) argue that just as focused constituents occupy the specifier position within a Focus Phrase, so too topicalized constituents occupy the specifier position within a Topic Phrase. This in turn raises the question of where Topic Phrases are positioned relative to other constituents within the clause. In this connection, consider the italicized clause in (6) below:

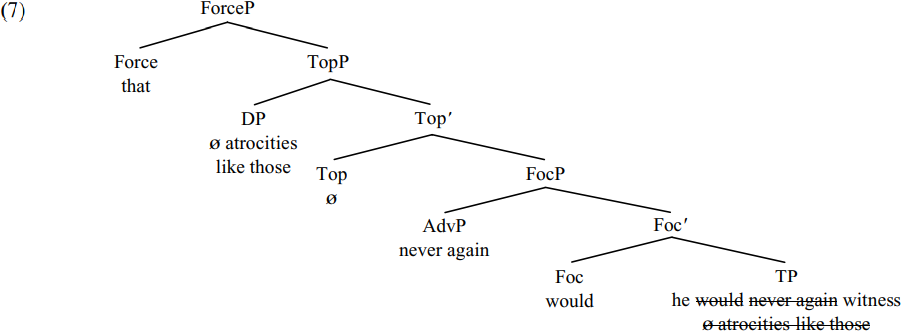

In the italicized clause in (6), that marks the declarative force of the clause; atrocities like those is the object of the verb witness and has been preposed in order to mark it as the topic of the sentence (since it refers back to the acts of rape, torture and mutilation mentioned in the previous sentence); the preposed negative adverbial phrase never again is a focused constituent, and hence requires auxiliary inversion. Thus, the italicized that-clause in (6) will have the simplified structure shown below:

In the italicized clause in (6), that marks the declarative force of the clause; atrocities like those is the object of the verb witness and has been preposed in order to mark it as the topic of the sentence (since it refers back to the acts of rape, torture and mutilation mentioned in the previous sentence); the preposed negative adverbial phrase never again is a focused constituent, and hence requires auxiliary inversion. Thus, the italicized that-clause in (6) will have the simplified structure shown below:

We can assume that the head Top constituent of the Topic Phrase contains an [EPP] feature and an uninterpretable topic feature, and that these attract a maximal projection which carries a matching interpretable topic feature to move to the specifier position within the Topic Phrase. If we further assume that Top is a weak head (and so does not carry an affixal [TNS] feature), we can account for the fact that the auxiliary would remains in the strong Foc position and does not raise to the weak Top position.

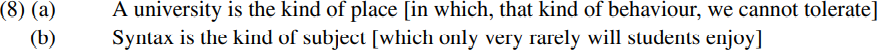

Rizzi’s split CP analysis raises interesting questions about the syntax of the kind of wh-movement operation which we find (inter alia) in interrogatives, relatives and exclamatives. Within the unitary (unsplit) CP analysis, it was clear that wh-phrases moved into spec-CP; but if CP can be split into a number of distinct projections (including a Force Phrase, a Topic Phrase and a Focus Phrase), the question arises as to which of these projections serves as the landing site for wh-movement. Rizzi (1997, p. 289) suggests that ‘relative operators occupy the highest specifier position, the spec of Force’. In this connection, consider the syntax of the bracketed relative clauses in (8) below:

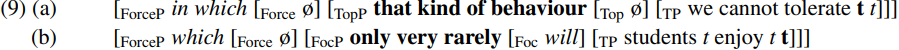

In (8a), the preposed wh-expression in which precedes the preposed topic that kind of behavior; in (8b) the preposed relative pronoun which precedes the preposed focused expression only very rarely. If Rizzi is right in suggesting that preposed relative operator expressions occupy specifier position within the Force Phrase, the bracketed relative clauses in (8a,b) above will have the simplified structures shown below:

In (8a), the preposed wh-expression in which precedes the preposed topic that kind of behavior; in (8b) the preposed relative pronoun which precedes the preposed focused expression only very rarely. If Rizzi is right in suggesting that preposed relative operator expressions occupy specifier position within the Force Phrase, the bracketed relative clauses in (8a,b) above will have the simplified structures shown below:

(Trace copies of moved constituents are shown as t and printed in the same type-face as their antecedent.)

(Trace copies of moved constituents are shown as t and printed in the same type-face as their antecedent.)

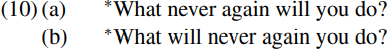

By contrast, Rizzi argues (1997, p. 299) that a preposed wh-operator expression ‘ends up in Spec of Foc in main questions’. If (as he claims) clauses may contain only a single Focus Phrase constituent, such an assumption will provide a straightforward account of the ungrammaticality of main-clause questions such as (10) below:

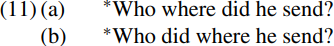

If both what and never again (when preposed) move into the specifier position within FocP, if Foc allows only one focused constituent as its specifier, and if no clause may contain more than one FocP constituent, it follows that (10a) will be ruled out by virtue of Foc having two specifiers (what and never again) and that (10b) will be ruled out by virtue of requiring two Focus Phrase constituents (one hosting what and another hosting never again). Likewise, multiple wh-movement questions (i.e. questions in which more than one wh-expression is preposed) like (11) below will be ruled out in a similar fashion:

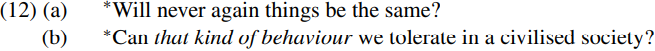

The assumption that preposed wh-phrases occupy spec-FocP has interesting implications for our claim that yes–no questions contain an interrogative operator whether (a null counterpart of whether). If this null operator (like other interrogative expressions) occupies spec-FocP, and if Foc is a strong head, it follows that inverted auxiliaries in main-clause yes–no questions like Has he left? will involve movement of the inverted auxiliary has into the head Foc position within FocP, with the specifier position in FocP being filled by a null counterpart of whether. This assumption would account for the ungrammaticality of sentences such as the following:

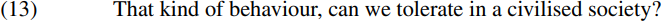

If never again is the specifier of a FocP constituent in (12a), the inverted auxiliary must be in a higher FocP projection whose specifier is whether. However, we have already seen in relation to sentences like (10) and (11) above that clauses may only contain one FocP constituent, so the ungrammaticality of (12a) can be attributed to the impossibility of stacking one FocP on top of another. Likewise, if that kind of behavior is a tropicalized constituent occupying the specifier position within a Topic Phrase in (12b) and if an inverted auxiliary like can in a yes–no question occupies the head Foc position of a FocP containing whether as its specifier, this means that FocP is positioned above TopP in (12b). Given the Head Movement Constraint, can will have to move through Top to get into Foc; but since Top is a weak head, can is prevented from moving through Top into Foc; and since Foc is a strong affixal head, the affix in Foc ends up being stranded without any verb to attach to. If we reverse the order of the two projections and position TopP above FocP, the resulting structure is fine, as we see from (13) below:

In (13), the topic that kind of behavior occupies the specifier position of a TopP which has a weak head, while the inverted auxiliary can occupies the strong head Foc position in a FocP which has the null operator whether as its specifier.

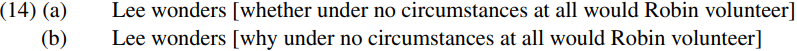

Although Rizzi argues that a preposed interrogative wh-expression moves into spec-FocP in main clauses, he maintains that a preposed wh-expression moves into a different position (spec-ForceP) in complement-clause questions. Some evidence in support of this claim comes from sentences such as the following (from Culicover 1991):

Here, the wh-expressions whether/why occur to the left of the focused negative phrase under no circumstances, suggesting that whether/why do not occupy specifier position within FocP but rather some higher position – and since ForceP is the highest projection within the clause, it is plausible to suppose that whether/why occupy spec-ForceP in structures like (14).

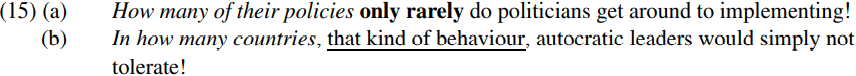

A question raised by Rizzi’s analysis of relative and interrogative wh-clauses is where preposed wh-expressions move in exclamative clauses. In this connection, consider (15) below:

In (15a), the italicized exclamative wh-expression how many of their policies precedes the bold-printed focused constituent only rarely, while in (15b) the exclamative wh-phrase in how many countries precedes the underlined topic that kind of behavior. And in (16) below:

In (15a), the italicized exclamative wh-expression how many of their policies precedes the bold-printed focused constituent only rarely, while in (15b) the exclamative wh-phrase in how many countries precedes the underlined topic that kind of behavior. And in (16) below:

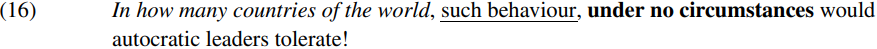

an italicized exclamative expression precedes both an underlined tropicalized expression and a bold-printed focused expression – though the resulting sentence is clearly highly contrived. All of this suggests that exclamative wh-expressions (like relative wh-expressions) move into the specifier position within ForceP.

an italicized exclamative expression precedes both an underlined tropicalized expression and a bold-printed focused expression – though the resulting sentence is clearly highly contrived. All of this suggests that exclamative wh-expressions (like relative wh-expressions) move into the specifier position within ForceP.

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة