Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Expletive there subjects

المؤلف:

Andrew Radford

المصدر:

Minimalist Syntax

الجزء والصفحة:

299-8

30-1-2023

3497

Expletive there subjects

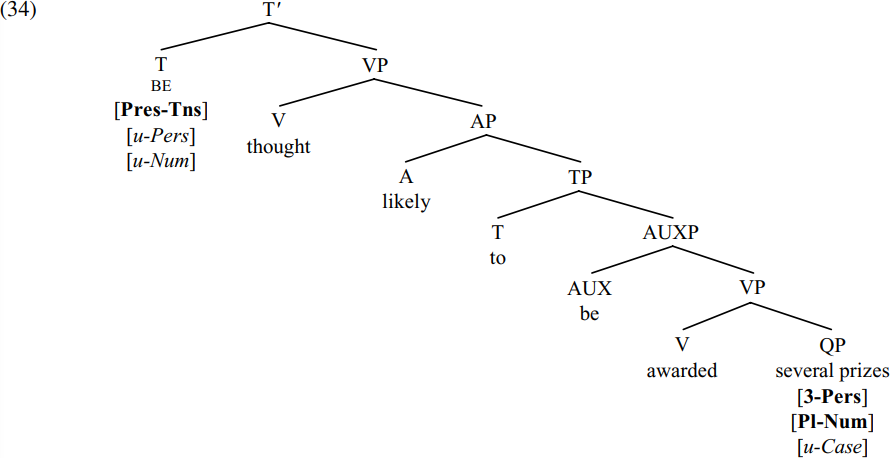

Having looked at the syntax of expletive it, we now turn to look at expletive there. As a starting point for our discussion, we’ll go back to the very first sentence we looked at, namely (1) There are thought likely to be awarded several prizes. Let’s suppose that the derivation proceeds as before, until we reach the stage in (2) above. However, let’s additionally assume that several prizes carries interpretable  -features (marking it as a third-person-plural expression) and an uninterpretable (and unvalued) casefeature. Let’s also assume (as in earlier discussions) that be carries an interpretable present-tense feature, and uninterpretable (and unvalued)

-features (marking it as a third-person-plural expression) and an uninterpretable (and unvalued) casefeature. Let’s also assume (as in earlier discussions) that be carries an interpretable present-tense feature, and uninterpretable (and unvalued)  -features. This being so, the structure formed when BE is merged with its VP complement will be that shown in simplified form below:

-features. This being so, the structure formed when BE is merged with its VP complement will be that shown in simplified form below:

Given the Earliness Principle, T-agreement will apply at this point in the derivation. Because BE is the highest head in the structure (in that it is the only head in the structure which is not c-commanded by another head), and because BE is active (by virtue of its uninterpretable

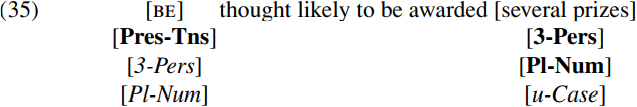

-features), BE serves as a probe which searches for a nominal goal within the structure containing it. The nominal several prizes can serve as a goal for the probe BE, since several prizes is active by virtue of carrying an uninterpretable case feature. By application of Feature-Copying (7), the unvalued person and number features on BE are given the same values as those on several prizes – as shown in simplified form in (35) below:

-features), BE serves as a probe which searches for a nominal goal within the structure containing it. The nominal several prizes can serve as a goal for the probe BE, since several prizes is active by virtue of carrying an uninterpretable case feature. By application of Feature-Copying (7), the unvalued person and number features on BE are given the same values as those on several prizes – as shown in simplified form in (35) below:

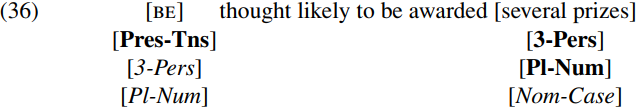

By application of Nominative Case Assignment (9), the unvalued case feature of the goal several prizes in (35) is assigned the value nominative as shown in (36) below, since the probe be carries finite tense (more specifically, present tense), and since the probe [BE] and the goal several prizes have matching

-feature values because both are third person plural:

-feature values because both are third person plural:

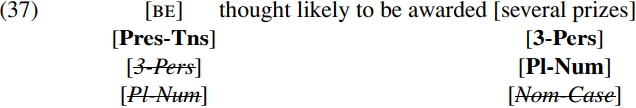

Via Feature-Deletion (14), the probe BE deletes the uninterpretable nominative case feature on several prizes, since BE is  -complete (by virtue of carrying both person and number features) and the

-complete (by virtue of carrying both person and number features) and the  -features of the probe BE match those of the goal several prizes. Conversely, via the same Feature-Deletion operation

-features of the probe BE match those of the goal several prizes. Conversely, via the same Feature-Deletion operation

(14), the goal several prizes deletes the uninterpretable person/number features on the probe BE, since the goal is  -complete (carrying both person and number features), and probe and goal have matching

-complete (carrying both person and number features), and probe and goal have matching  -feature values. Feature-Deletion yields:

-feature values. Feature-Deletion yields:

We have thus deleted all uninterpretable case/agreement features on both probe and goal, as required.

However, BE also has an [EPP] feature (not shown above) requiring it to project a structural subject. In (1) There are thought likely to be awarded several prizes, the [EPP] requirement of [T BE] is satisfied by merging expletive there in spec-TP. Let’s assume that (like expletive it), expletive there carries no case feature (and hence has no genitive form, as we see from the ungrammaticality of ∗She was upset by there’s being nobody to help her). More precisely, let’s follow Chomsky (1998, 1999, 2001) in positing that the only feature carried by expletive there is an uninterpretable person feature, and let’s further suppose that there is intrinsically third person (consistent with the fact that a number of other words beginning with th- are third person – e.g. this, that, these, those and the). Accordingly, merging there in spec-TP will derive the structure shown in abbreviated form below:

The pronoun there serves as a probe because it is the highest head in the structure, and because it is active by virtue of carrying an uninterpretable third-person  - feature. It therefore searches for a c-commanded goal to agree with. Let’s suppose that agreement (of the kind we are concerned with here) involves a T–nominal relation (i.e. a relation between T and a noun/pronoun expression): this being so, there (being a pronominal probe) will search for an active T constituent to serve as its goal, and find [T BE]. BE is an active goal for the probe there in (38) because be contains uninterpretable person/number features: these have been marked as invisible to the semantic component (via Feature-Deletion), but remain visible and active in the syntax in accordance with the Feature Visibility Convention (13). Accordingly, Feature-Deletion (14) applies, and the goal BE deletes the matching uninterpretable third-person feature carried by the probe there. This is possible because there is active as a probe and BE is active as a goal (as we have just seen), and because the goal BE is

- feature. It therefore searches for a c-commanded goal to agree with. Let’s suppose that agreement (of the kind we are concerned with here) involves a T–nominal relation (i.e. a relation between T and a noun/pronoun expression): this being so, there (being a pronominal probe) will search for an active T constituent to serve as its goal, and find [T BE]. BE is an active goal for the probe there in (38) because be contains uninterpretable person/number features: these have been marked as invisible to the semantic component (via Feature-Deletion), but remain visible and active in the syntax in accordance with the Feature Visibility Convention (13). Accordingly, Feature-Deletion (14) applies, and the goal BE deletes the matching uninterpretable third-person feature carried by the probe there. This is possible because there is active as a probe and BE is active as a goal (as we have just seen), and because the goal BE is  -complete (having both person and number features), and the third-person feature carried by the probe there matches the third-person feature carried by the goal BE. Deleting the uninterpretable person feature of there, and merging the resulting TP with a null complementizer carrying an interpretable declarative force feature [Dec-Force], derives the CP shown in skeletal form below:

-complete (having both person and number features), and the third-person feature carried by the probe there matches the third-person feature carried by the goal BE. Deleting the uninterpretable person feature of there, and merging the resulting TP with a null complementizer carrying an interpretable declarative force feature [Dec-Force], derives the CP shown in skeletal form below:

Only the bold-printed interpretable features will be processed by the semantic component, not the barred italicized uninterpretable features (since these have all been deleted and deletion makes features invisible to the semantic component, while leaving them visible to the syntactic and phonological components); both the interpretable and uninterpretable features will be processed by the phonological component where BE will be spelled out as are. (On colloquial structures like There’s lots of people in the room, see den Dikken 2001.)

Only the bold-printed interpretable features will be processed by the semantic component, not the barred italicized uninterpretable features (since these have all been deleted and deletion makes features invisible to the semantic component, while leaving them visible to the syntactic and phonological components); both the interpretable and uninterpretable features will be processed by the phonological component where BE will be spelled out as are. (On colloquial structures like There’s lots of people in the room, see den Dikken 2001.)

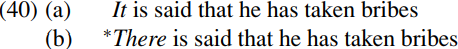

An important question to ask in the context of our discussion of expletive it and expletive there is what factors determine the choice of expletive in a particular sentence. In this connection, let’s ask why expletive there can’t be used in place of expletive it in sentences like (40b) below:

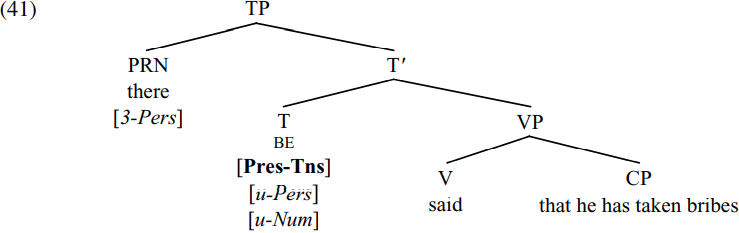

Let’s suppose that merging BE with the VP headed by the verb said forms the structure shown in (19) above, and that subsequently merging there in spec–TP derives the structure shown in (41) below:

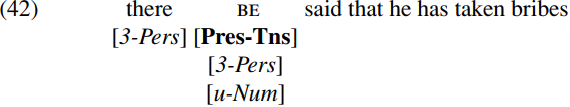

Because it is the highest head in the structure, and because it is active by virtue of its uninterpretable person feature, there serves as a probe. BE serves as the goal for there because BE is c-commanded by there, and be itself is active by virtue of its uninterpretable person/number features. Via Feature-Copying (7), the unvalued person feature of BE will be assigned the same third-person value as there – as shown in schematic form below:

Via Feature-Deletion (14), BE can delete the uninterpretable person feature of there, because BE is  -complete and the person features of BE and there have matching values. However, there cannot delete the person feature of BE, since there is

-complete and the person features of BE and there have matching values. However, there cannot delete the person feature of BE, since there is  -incomplete (in that it has person but not number), and only a

-incomplete (in that it has person but not number), and only a  -complete

-complete  can delete one or more features of ß. Accordingly, the structure which results after Feature-Deletion applies is:

can delete one or more features of ß. Accordingly, the structure which results after Feature-Deletion applies is:

However, the resulting derivation will ultimately crash, for two reasons. Firstly, the number feature on BE has remained unvalued, and the PF component cannot process unvalued features. And secondly, the uninterpretable person and number features on be have not been deleted, and the semantic component cannot process uninterpretable features. In other words, our assumptions about the differences between expletive it and expletive there allow us to provide a principled account of why (40a) It is said that he has taken bribes is grammatical, but (40b) ∗There is said that he has taken bribes is not.

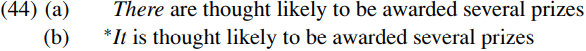

Now let’s ask why expletive it can’t be used in place of there in a sentence like (44b) below:

One way of answering this question is by making the assumption outlined below:

The requirement in (45iii) for T to attract the closest matching goal is a consequence of the Attract Closest Principle. (45i) stipulates the indefiniteness requirement without explaining it. An interesting possibility to explore would be that in expletive there structures, the associate is indefinite because it has no person properties, so that there is inserted in order to value the person properties of T (though see Frampton and Gutmann 1999 for an alternative explanation. See also Lasnik 2001 on the nature of EPP.)

The requirement in (45iii) for T to attract the closest matching goal is a consequence of the Attract Closest Principle. (45i) stipulates the indefiniteness requirement without explaining it. An interesting possibility to explore would be that in expletive there structures, the associate is indefinite because it has no person properties, so that there is inserted in order to value the person properties of T (though see Frampton and Gutmann 1999 for an alternative explanation. See also Lasnik 2001 on the nature of EPP.)

It follows from (45) that in structures like (34) where [T BE] c-commands (and agrees in person and number with) an indefinite nominal (several prizes), expletive there can be used but not expletive it, so deriving (44a) There are thought likely to be awarded several prizes. Conversely in structures like (19) where there is no matching goal accessible to the probe [T BE], it can be used but not there – so deriving (18a) It is said that he has taken bribes. It also follows from (45) that neither expletive can be used in structures like the following:

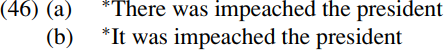

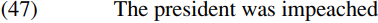

This is because was in (46) c-commands and agrees in person and number with the definite goal the president, so that the conditions for the use of either expletive in (45i,ii) are not met. The only way of deleting the [EPP] feature of T in such a case is to passivize the definite DP the president, so deriving:

So, we see that the EPP Generalization in (45) provides a descriptively adequate characterization of data like (40), (44), (46) and (47). (See Bowers 2002 for an alternative account of the there/it distinction in expletives.)

However, our so-called ‘generalization’ in (45) is little more than a descriptive stipulation, and begs the question of why the relevant restrictions on the use of expletives should hold. A preferable solution would be to see the choice between expletive there and expletive it as one rooted in UG principles.

Reasoning along these lines, one possibility would be to posit that economy considerations dictate that we use an expletive carrying as few uninterpretable features as possible. In a structure like (19), the expletive has to serve two functions: (i) to satisfy the [EPP] requirement for T to have a specifier with person and/or number properties; and (ii) to value the unvalued person/number features of [T BE]. Hence only expletive it can be used, since this carries both person and number. But in a structure like (2), the expletive is not needed to value the person/number features of [T BE] since these are valued by several prizes; rather, the expletive serves only to satisfy the requirement for T to have a specifier with person and/or number features. In this situation, we might suppose, there is preferred to it because there carries only person, and economy considerations dictate that we use as few uninterpretable features as possible.

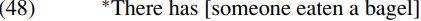

We have followed Chomsky in assuming that expletive there is a ‘dummy’ pronoun directly merged in spec-TP. However, just as there are some who believe that expletive it originates internally within VP, so too there are some who believe that expletive there originates internally within VP, perhaps with a locative function (as suggested by Moro 1997). Bowers (2002, p. 195) argues that the ungrammaticality of transitive expletive structures such as the following in Standard English:

cannot be accounted for under Chomsky’s spec-TP analysis of expletive there, since nothing in the spec-TP account prevents has from agreeing with (and assigning nominative case to)someone, with expletive there being inserted in spec-TP in order to delete the [EPP] feature of T. A principled way of ruling out sentences like (48), Bowers argues, is by supposing that expletive there originates in spec-VP as a nonthematic subject – and hence it can only occur in intransitive VPs which (by their very nature) do not have a thematic subject.

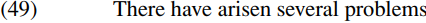

We can illustrate how such an analysis might work in terms of a sentence such as (49) below:

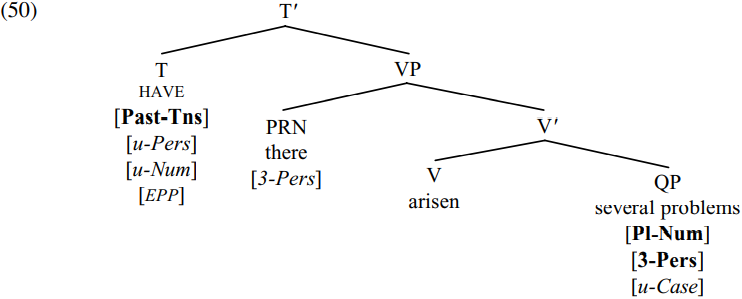

The verb arise is an unaccusative predicate which projects a complement, but no thematic subject. Precisely because it projects no thematic subject, it can project an expletive subject (on Bowers’s assumption that a predicate only allows an expletive subject if it has no thematic subject). This means that expletive there will initially be merged as the specifier of the VP headed by arisen in (49), so that at the stage of derivation when HAVE is merged with its VP complement, we have the structure shown in (50) below:

[T HAVE] will then probe for active matching goals which carry person and/or number features, and locates two such active goals, there and several problems. Accordingly, T simultaneously agrees with both there and several problems – resulting in multiple agreement (i.e. agreement between a probe and more than one matching goal). Clearly, this will only yield a successful outcome if the associate carries the same third-person feature as there – thereby accounting for the observation by Sigurðsson (1996) that expletive associates must be third-person expressions. The [EPP] feature of T simultaneously attracts the closest active goal, so triggering movement of there to spec-TP. We can assume that all the various operations affecting a given probe (like T in (50) above) apply simultaneously, so that agreement with there, agreement with several problems and movement of there to spec-TP all apply at the same time.

A potential problem posed by analyzing expletive there as a (perhaps locative) quasi-argument initially merged in spec-VP is that (unlike expletive it in sentences such as (31) above) expletive there cannot serve as a controller for PRO – as we see from (51) below:

If quasi-arguments have the property of being able to serve as controllers of PRO, sentences like (51) might be thought to argue against a VP-internal origin for expletive there. However, a straightforward way of accounting for the contrast between (31) and (51) is to suppose that PRO requires an antecedent with both person and number features, and that expletive it carries both of these features, but expletive there carries only person.

A VP-internal analysis of expletives like that in (50) also offers significant theoretical advantages over Chomsky’s TP analysis, in that it provides us with a way of avoiding two potentially problematic aspects of Chomsky’s analysis. One is that although a probe is generally the head of a containing projection (so that the head T of TP is the probe in most of the structures we have looked at), Chomsky’s TP analysis of expletives has to stipulate that a specifier can also serve as a probe when it is an expletive pronoun like there/it – a claim which is hard to square with his (2001) view that specifier–head agreement should be eliminated from the set of operations permitted by UG. By contrast, the VP-internal analysis of expletives allows us to maintain the stronger claim that only a head can be a probe. A second feature of Chomsky’s analysis (illustrated in (38) above) is that he needs to assume that a T which has already had its person/number features valued and deleted by agreement with an indefinite associate can nonetheless serve as an active goal for agreement with an expletive probe. One way round this problem (suggested by Pesetsky and Torrego 2001) is to say that the relevant features are marked for deletion (or metaphorically speaking, sentenced to death) on the TP cycle, but not actually deleted (or, metaphorically speaking, executed) until a later stage of derivation (at the end of the CP cycle/phase). However, any such intrinsically undesirable splitting of deletion into two processes can be avoided under the account suggested here, which allows us to posit a unitary treatment of deletion along the lines of (52) below:

However, it should be noted that while (52) is compatible with a VP analysis of expletives, it is not compatible with Chomsky’s claim that expletive there is directly merged in spec-TP.

A crucial premise of our alternative account of expletives is that in structures like (50), a T-probe can agree simultaneously with multiple goals (so that have simultaneously agrees in person with there and in person and number with several problems). However, this assumption raises interesting questions about how agreement works in transitive sentences like:

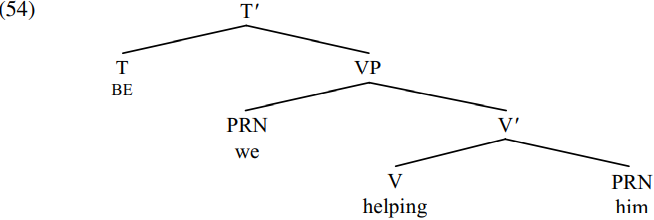

Given the assumptions we are making here, (53) will be derived as follows. The verb helping merges with its THEME complement him to form the V-bar helping him. This V-bar is in turn merged with its AGENT argument we to form the VP we helping him. The resulting VP is then merged with a present-tense T constituent to form the T-bar shown in simplified form in (54) below:

Given the Earliness Principle, T will serve as a probe at this point and look for one or more nominal goals to value (and delete) its unvalued person/number features. However, if (as we assumed in our discussion of (50) above) a probe can agree with multiple goals, an important question to ask is why T can’t agree with both the subject we and the complement him. If (contrary to fact) multiple agreement were permitted in structures like (54), it would cause the derivation to crash because the person/number features of BE would have to be valued as first person plural in order to agree with the subject we and as third person singular in order to agree with the object him, and this would clearly lead to conflicting requirements on how the person/number features of BE should be valued. In reality, T agrees with the subject we in transitive structures like (54) and not with the object him. But in a framework which allows a probe to agree with multiple goals, how can we rule out agreement between T and the object of a transitive verb?

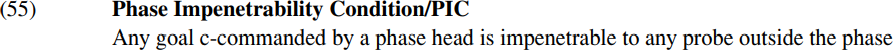

One answer to this question is provided by the Phase Impenetrability Condition, which we formulated in (23) above in the manner set out in (55) below:

In our earlier discussion of PIC, we noted Chomsky’s (1999, p. 9) claim that phases are ‘propositional’ in nature, and that accordingly CPs are phases. However, Chomsky claims that transitive verb phrases (but not intransitive VPs) are also propositional in nature and hence phases, by virtue of the fact that transitive VPs contain a complete thematic (argument structure) complex, including an external argument in spec-VP.

In our earlier discussion of PIC, we noted Chomsky’s (1999, p. 9) claim that phases are ‘propositional’ in nature, and that accordingly CPs are phases. However, Chomsky claims that transitive verb phrases (but not intransitive VPs) are also propositional in nature and hence phases, by virtue of the fact that transitive VPs contain a complete thematic (argument structure) complex, including an external argument in spec-VP.

If transitive VPs are phases, and PIC allows only constituents on the edge (i.e. in the head or specifier position) of a phase to be accessible to a higher probe, it follows that in a structure like (54) above, the T constituent BE will only be able to agree with the subject we on the edge of the transitive VP phase, not with the object him which lies within the (c-command) domain of the transitive phase head helping. By contrast, in expletive structures like (50), PIC will not prevent the T constituent have from agreeing with both there and several problems, since the VP headed by the unaccusative verb arisen is intransitive (its specifier there not being an external argument but rather being a non-referential expletive pronoun).

If we adopt the Feature Inactivation Hypothesis (52), there is also another way in which we can prevent agreement between T and the object of a transitive verb in structures like (54). If the object him enters the derivation with an unvalued case feature and (in accordance with the Earliness Principle) the relevant case feature is valued as accusative (and deleted) as soon as him is merged with the transitive verb helping, it follows that once we reach the stage of derivation shown in (54) above, the accusative case feature carried by him will have been deleted, so making him inactive for agreement with T. (We look at accusative case assignment, so will say no more about it for the time being.)

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)