Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Case Properties Of Subjects

المؤلف:

Andrew Radford

المصدر:

Minimalist Syntax

الجزء والصفحة:

134-4

16/11/2022

2188

Case properties of subjects

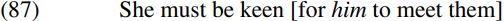

A question which we haven’t addressed so far is how subjects are case-marked. In this connection, consider how the italicized subject of the bracketed infinitive complement clause in (87) below is assigned accusative case:

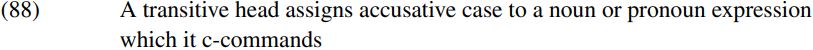

Since for is a transitive complementizer, it seems plausible to suppose that the infinitive subject him is assigned accusative case by the transitive complementizer for – but how? We’ve already seen that the relation c-command plays a central role in our characterization of a wide range of disparate phenomena, including the binding of anaphors, morphological operations like Affix Hopping, phonological operations like have-cliticisation, and so on. Let’s therefore explore the possibility that c-command is also central to case assignment. More particularly, let’s suppose that:

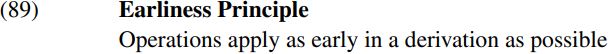

In addition, let’s follow Pesetsky (1995) in positing the following UG principle governing the application of grammatical (and other kinds of linguistic) operations:

In the light of (88) and (89), let’s look at the derivation of the bracketed complement clause in (87). The first step is for the verb meet to be merged with its pronoun complement them to form the VP shown in (90) below:

Meet is a transitive verb which c-commands the pronoun them. Since (88) specifies that a transitive head assigns accusative case to a pronoun which it c-commands, and since the Earliness Principle specifies that operations like case assignment must apply as early as possible in a derivation, it follows that the pronoun them will be assigned accusative case by the transitive verb meet at the stage of derivation shown in (90).

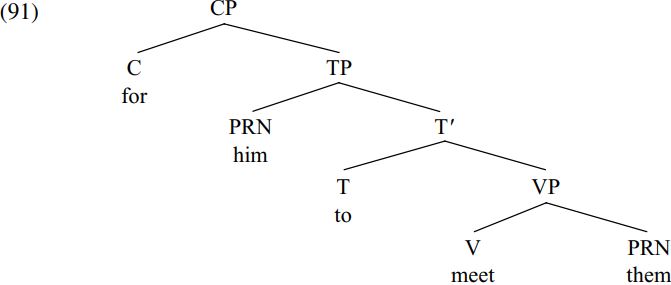

The derivation then continues by merging the infinitive particle to with the VP in (90), so forming the T-bar to meet them. The resulting T-bar is merged with its subject him to form the TP him to meet them. This TP in turn is merged with the complementizer for to form the CP shown in (91) below:

For is a transitive complementizer and c-commands the infinitive subject him. Since (88) specifies that a transitive head assigns accusative case to a pronoun which it c-commands, and since the Earliness Principle specifies that operations like case assignment must apply as early as possible in a derivation, it follows that the pronoun him will be assigned accusative case by the transitive complementizer for at the stage of derivation shown in (91). This account of the case-marking of infinitive subjects can be extended from accusative subjects of for infinitives in structures like (91) to accusative subjects of ECM infinitives in structures like (83) They believe [him to be innocent], since the transitive verb believe c-commands the infinitive subject him in (83). (As we shall see, a tacit assumption underlying the case assignment analysis is that noun and pronoun expressions enter the derivation carrying a case feature which is initially unvalued, and which is then valued as nominative, accusative or genitive by a c-commanding head of an appropriate kind.)

Having looked at how accusative subjects are case-marked, let’s now turn to look at the case-marking of nominative subjects. In this connection, consider the case-marking of the italicized subjects in (92) below:

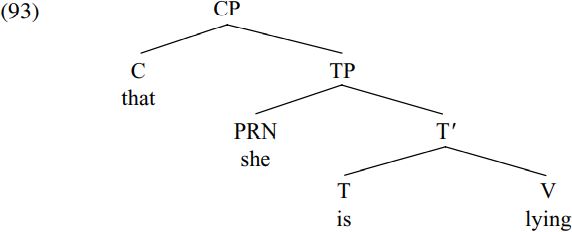

Consider first how the complement clause subject she is assigned case. The bracketed complement clause in (92) has the structure (93) below:

If we are to develop a unitary theory of case-marking, it seems plausible to suppose that nominative subjects (just like accusative subjects) are assigned case under c-command by an appropriate kind of head. Since the finite complementizer that in (93) c-commands the subject she, let’s suppose that she is assigned nominative case by the complementizer that (in much the same way as the infinitive subject him in (91) is assigned accusative case by the transitive complementizer for). More specifically, let’s assume that

In (93), the only noun or pronoun expression c-commanded by the finite complementizer that is the clause subject she, which is therefore assigned nominative case in accordance with (94).

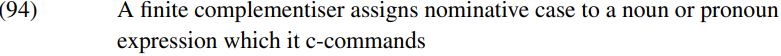

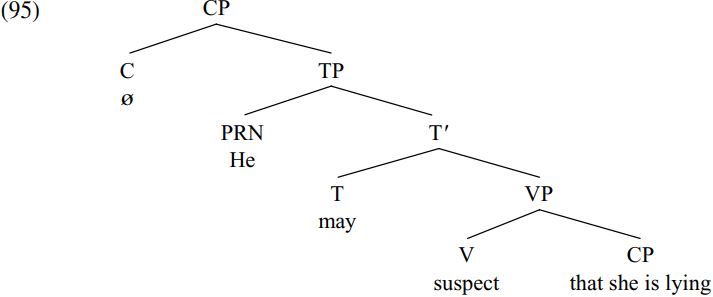

But how can we account for the fact that the main-clause subject he in (92) is also assigned nominative case? The answer is that all canonical clauses – including all main clauses – are CPs introduced by a complementizer, and that if the clause contains no overt complementizer, it is headed by a null complementiser. This being so, the main clause in (92) will have the structure (95) below:

Thus, the overall clause is headed by a null finite declarative complementizer [C ø] in much the same way as the Arabic main clauses in (61) are headed by an overt complementizer, and it is this null finite complementizer which assigns nominative case to the subject he in (95) in accordance with (94) above, since the complementizer ø c-commands the pronoun he. (On the possibility of a finite C being a nominative case assigner, see Chomsky 1999, p. 35, fn.17.)

However, an interesting complication arises in relation to the Arabic data in (61) above. Sentence (61a) is introduced by the transitive finite complementizer ? inna ‘that’ and the subject lwalada ‘the boy’ is assigned accusative case in accordance with (88). By contrast, sentence (61b) is introduced by the finite complementizer hal ‘if’: this is not transitive and assigns nominative case to the subject lwaladu (which therefore carries the nominative ending -u rather than the accusative ending -a). Such considerations suggest that we need to revise (94) by adding the italicized condition shown in (96) below:

Since none of the English finite complementizers (e.g. if, that, and the null finite complementizer found in main clauses) are transitive, all finite clauses in English will have nominative subjects.

and the null finite complementizer found in main clauses) are transitive, all finite clauses in English will have nominative subjects.

Having looked at accusative and nominative subjects, let’s now turn to consider the null PRO subjects found in control clauses. If we suppose that it is a defining characteristic of all pronouns that they carry case, then PRO too must carry case – and indeed there is some evidence that this is so. Part of the relevant evidence comes from structures like (97) below which contain a (bold-printed) floating quantifier which modifies the (italicized) subject of its clause, but is separated from (and positioned lower than) the subject:

In a language like Icelandic which has a richer morphology than English, floating quantifiers agree in case with their antecedent (i.e. with the expression which they modify). In a structure like (98) below (from Sigurðsson 1991, p. 331) the verb leiðist ‘got bored’ requires a subject with dative (= dat) case, and hence a floating quantifier modifying the subject also has dative case:

Interestingly, when the relevant verb is used in a control clause, a floating quantifier modifying the subject of the control clause has dative case, as the following example (from Sigurðsson ibid.) shows:

Why should the floating quantifier in (99) be dative? It doesn’t carry the same case as the main-clause subject strakarnir ´ ‘the boys’, since the latter has nominative (= NOM) case. On the contrary, the floating quantifier carries the same case as (and is construed as quantifying) the null PRO subject of its clause, and PRO has dative case because it is an idiosyncratic property of the relevant verb in Icelandic that it requires a dative subject. (Icelandic is said to be a language with quirky case subjectsin that some verbs require dative subjects, others require accusative subjects and so on. On dative and quirky subjects, see Moore and Perlmutter 2000, and Sigurðsson 2002.)

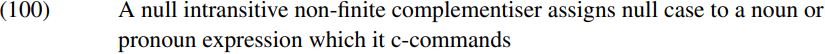

In short, the syntax of floating quantifiers in Icelandic makes it clear that PRO has case properties of its own. But what case does PRO carry in a morphologically impoverished language like English? Chomsky and Lasnik (1995, pp. 119–20) suggest that the subject of a control clause carries what they call null case. The morphological effect of null case is to ensure that a pronoun is unpronounced – just as the morphological effect of nominative case is to ensure that (e.g.) a third person-masculine-singular pronoun is pronounced as he. But how is PRO assigned null case? If we are to attain a unitary account of case-marking under which a noun or pronoun expression is case-marked by a head which c-commands it, a plausible answer is the following:

It follows from (100) that PRO in a structure like (72b) above will be assigned null case by the null (non-finite, intransitive) complementizer which c-commands PRO.

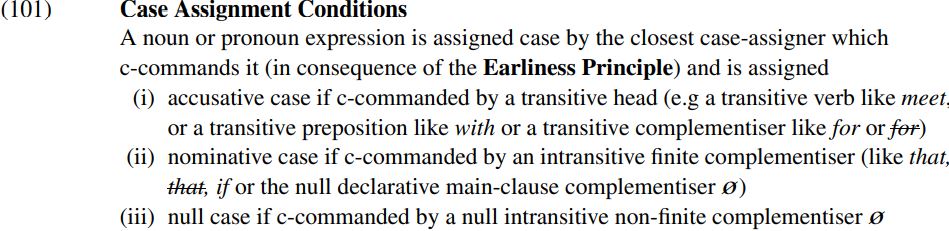

We can conflate the various claims made about case-marking above into (101) below:

If we assume that PRO is the only exponent of null case in English, it follows from (101iii) that control infinitive clauses (which are headed by a null-case-assigning complementizer) will always require a PRO subject.

If we assume that PRO is the only exponent of null case in English, it follows from (101iii) that control infinitive clauses (which are headed by a null-case-assigning complementizer) will always require a PRO subject.

What is particularly interesting about our discussion of case-marking here from a theoretical point of view is that it provides yet more evidence for the centrality of the relation c-command in syntax. (See Frank and Vijay-Shanker 2001 for a technical defense of the primitive nature of c-command.) An important theoretical question to ask at this juncture is why c-command should be such a fundamental relation in syntax. From a Minimalist perspective (since the goal of Minimalism is to utilize only theoretical apparatus which is conceptually necessary), the most principled answer would be one along the following lines. It is clear that the operation Merge (which builds phrases out of words, and sentences out of phrases) is conceptually necessary, in that (e.g.) to form a prepositional phrase like to Paris out of the preposition to and the noun Paris, we need some operation like Merge which combines the two together. In order to achieve the Minimalist goal of developing a constrained theory of Universal Grammar/UG which makes use only of concepts and constructs which are conceptually necessary, we can suppose that the only kind of syntactic relations which UG permits us to make use of are those created by the operation Merge. Now, two structural relations created by the operation Merge are contain(ment) and c-command in that if we merge a head X with a complement YP to form an XP projection, XP contains X, YP and all the constituents of YP, and X c-commands YP and all the constituents of YP. Minimalist considerations therefore lead us to hypothesize that the containment and c-command relations created by merger are the only primitive relations in syntax.

Our discussion here shows that case-marking phenomena can be accounted for in a principled fashion within a highly constrained Minimalist framework which makes use of the c-command relation which is created by the operation Merge. Note that a number of other grammatical relations which traditional grammars make use of (e.g. relations like subjecthood and objecthood) are not relations which can be used within the Minimalist framework. For example, a typical characterization of accusative case assignment in traditional grammar is that a transitive verb or preposition assigns accusative case to its object. There are two problems with carrying over such a generalization into the framework we are using here. The first is that Minimalism is a constrained theory which does not allow us to appeal to the relation objecthood, only to the relations contain and c-command; the second is that the traditional objecthood account of accusative case assignment is empirically inadequate, in that it fails to account for the accusative case-marking of an infinitive subject by a transitive complementizer in structures like (91), because him is not the object of the complementizer for but rather the subject of to meet them (and the same holds for accusative subjects of ECM infinitive structures like (83) above). As our discussion later unfolds, it will become clear that there are a number of other syntactic phenomena which can be given a principled description in terms of the relations contain and c-command.

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)