Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension

Teaching Methods

Teaching Methods|

Read More

Date: 2023-05-19

Date: 2023-10-20

Date: 2023-10-21

|

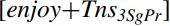

Our analysis of the kind of auxiliariless clauses as TPs headed byaT which has a null phonetic spellout suggests the more general hypothesis that:

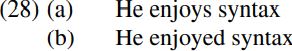

Such a hypothesis has interesting implications for finite clauses such as the following which contain a finite verb but no auxiliary:

It implies that we should analyze auxiliariless finite clauses like those in (28a,b) above as TP constituents which have the respective structures shown in (29a,b) below:

Structures like those in (29) would differ from null-auxiliary structures like (23) He could have helped her or she  have helped him and (26) He

have helped him and (26) He  gonna be there in that they don’t contain a silent counterpart of a specific auxiliary like could or is, but rather simply don’t contain any auxiliary at all.

gonna be there in that they don’t contain a silent counterpart of a specific auxiliary like could or is, but rather simply don’t contain any auxiliary at all.

However, there’s clearly something very odd about a null T analysis like (29) if we say that the relevant clauses are TPs which are headed by a T constituent which contains absolutely nothing. For one thing, a category label like T is an abbreviation for a set of features carried by a lexical item – hence, if we posit that structures like (29) are TPs, the head T position of TP has to be occupied by some kind of lexical item. Moreover, the structures which are generated by the syntactic component of the grammar are eventually handed over to the semantic component to be assigned a semantic interpretation, and it seems reasonable to follow Chomsky (1995) in requiring all constituents in a syntactic structure to play a role in determining the meaning of the overall structure. If so, it clearly has to be the case that the head T of TP contains some item which contributes in some way to the semantic interpretation of the sentence. But what kind of item could T contain?

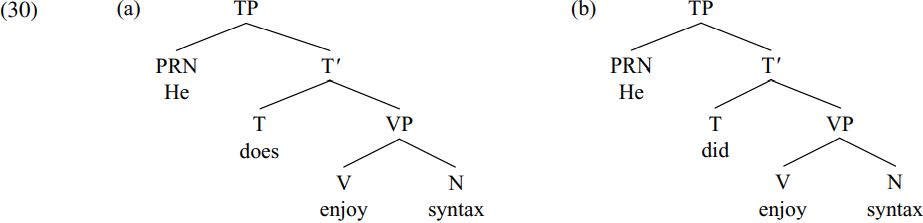

In order to try and answer this question, it’s instructive to contrast auxiliariless structures like those in (29) above with auxiliary-containing structures like those in (30) below:

The head T position in TP is occupied by the present-tense auxiliary does in (30a), and by the past-tense auxiliary did in (30b). If we examine the internal morphological structure of these two words, we see that does contains the present-tense affix -s, and that did contains the past-tense affix -d (each of these affixes being attached to an irregular stem form of the auxiliary DO). In schematic terms, then, we can say that the head T constituent of TP in structures like (30) is of the form auxiliary +tense affix.

The head T position in TP is occupied by the present-tense auxiliary does in (30a), and by the past-tense auxiliary did in (30b). If we examine the internal morphological structure of these two words, we see that does contains the present-tense affix -s, and that did contains the past-tense affix -d (each of these affixes being attached to an irregular stem form of the auxiliary DO). In schematic terms, then, we can say that the head T constituent of TP in structures like (30) is of the form auxiliary +tense affix.

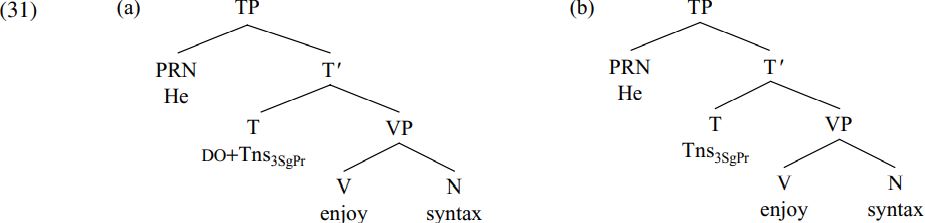

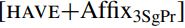

If we now look back at the auxiliariless structures in (29), we see that the head V position of VP in these structures is occupied by the verbs enjoys and enjoyed, and that these have a parallel morphological structure, in that they are of the form verb+ tense affix. So, what finite clauses like (29) and (30) share in common is that in both cases they contain an (auxiliary or main) verb carrying a tense affix. In structures like (30) which contain an auxiliary like do, the tense affix is attached to the auxiliary; in structures like (29) which contain no auxiliary, the tense affix attaches instead to the main verb enjoy. If we make the reasonable assumption that (as its label suggests) T is the locus of the tense properties of a finite clause (in the sense that T is the constituent which carries its tense features), an interesting possibility to consider is that the relevant tense affix (in both types of clause structure) originates in the head T position of TP. Since tensed verbs agree with their subjects in person and number, let us suppose that the tense affix (below abbreviated to Tns) also carries person and number properties. On this view, sentences like He does enjoy syntax and He enjoys syntax would have the respective syntactic structures indicated in (31a,b) below, where [3SgPr] is an abbreviation for the features [third-person, singular-number, present-tense]:

The two structures share in common the fact that they both contain a tense affix (Tns) in T; they differ in that the tense affix is attached to the auxiliary do in (31a), but is unattached in (31b) because there is no auxiliary in T for the affix to attach to.

The two structures share in common the fact that they both contain a tense affix (Tns) in T; they differ in that the tense affix is attached to the auxiliary do in (31a), but is unattached in (31b) because there is no auxiliary in T for the affix to attach to.

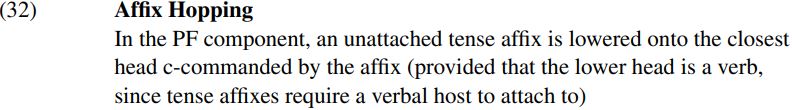

Under the analysis in (31), it is clear that T in auxiliariless clauses like (31b) would not be empty, but rather would contain a tense/agreement affix whose semantic contribution to the meaning of the overall sentence is that it marks tense. But what about the phonetic spellout of the tense affix? In a structure like (31a), it is easy to see why the (third-person-singular-present) tense affix is ultimately spelled out as an s-inflection on the end of the auxiliary does, because the affix is directly attached to the auxiliary do in T. But how come the affix ends up spelled out as an s-inflection on the main verb enjoys in a structure like (31b)? We can answer this question in the following terms. Once the syntax has formed a clause structure like (31), the relevant syntactic structure is then sent to the semantic component to be assigned a semantic interpretation, and to the PF component to be assigned a phonetic form. In the PF component, a number of morphological and phonological operations apply. One of these morphological operations is traditionally referred to as Affix Hopping, and can be characterized informally as follows:

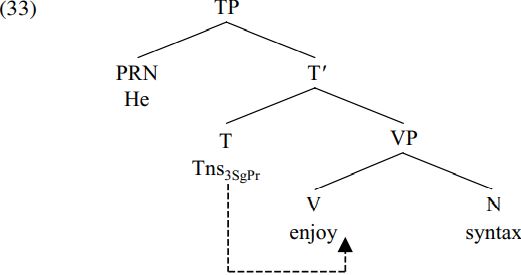

Because the closest head c-commanded by T in (31b) is the verb enjoy (which is the head V of VP), it follows that (in the PF component) the unattached affix in T will be lowered onto the verb enjoy via the morphological operation of Affix Hopping, in the manner shown by the arrow in (33) below:

Since inflections in English are suffixes, we can assume that the tense affix will be lowered onto the end of the verb enjoy, to derive the structure  .

.

Since enjoy is a regular verb, the resulting structure will ultimately be spelled out in the phonology as the form enjoys.

What we have done so far is sketch out an analysis of auxiliariless finite clauses as TPs headed by a T constituent containing an abstract tense affix which is subsequently lowered onto the verb by an Affix Hopping operation in the PF component (so resulting in a clause structure which looks as if it contains no T constituent). However, an important question to ask at this juncture is why we should claim that auxiliariless clauses contain an abstract T constituent. From a theoretical point of view, one advantage of the abstract T analysis is that it provides a unitary characterisation of the syntax of clauses, since it allows us to say that all clauses contain a TP projection, that the subject of a clause is always in spec-TP (i.e. always occupies the specifier position within TP), that a finite clause always contains an (auxiliary or main) verb carrying a tense affix, and so on. Lending further weight to theory-internal considerations such as these is a substantial body of empirical evidence, as we shall see.

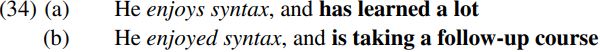

One argument in support of the tense affix analysis comes from coordination facts in relation to sentences such as:

In both sentences, the italicized string enjoys syntax/enjoyed syntax has been coordinated with a bold-printed constituent which is clearly a T-bar in that it comprise a present-tense auxiliary (has/is) with a verb phrase complement (learned a lot/taking a follow-up course). On the assumption that only the same kinds of constituent can be conjoined by and, it follows that the italicized (seemingly T-less) strings enjoys syntax/enjoyed syntax must also be T-bar constituents; and since they contain no overt auxiliary, this means they must contain an abstract T constituent of some kind – precisely as the tense affix analysis in (33) claims.

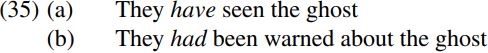

A direct consequence of the tense affix analysis (33) of auxiliariless finite clauses is that finite auxiliaries and finite main verbs occupy different positions within the clause: finite auxiliaries occupy the head T position of TP, whereas finite main verbs occupy the head V position of VP. An interesting way of testing this hypothesis is in relation to the behavior of items which have the status of auxiliaries in some uses, but of verbs in others. One such word is have. In the kind of uses illustrated in (35) below, HAVE is a perfect auxiliary (and so requires the main verb to be in the perfect participle form seen/been):

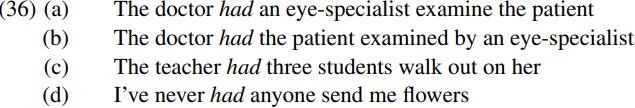

However, in the uses illustrated in (36) below, HAVE is causative or experiential in sense (and so has much the same meaning as cause or experience):

By traditional tests of auxiliarihood, perfect have is an auxiliary, and causative/experiential have is a main verb: e.g. perfect have can undergo inversion (Has she gone to Paris?) whereas causative/experiential have cannot (∗Had the doctor an eye specialist examine the patient?). In terms of the assumptions we are making here, this means that finite forms of HAVE are positioned in the head T position of TP in their perfect use, but in the head V position of VP in their causative or experiential use.

Evidence in support of this claim comes from facts about cliticisation. We noted earlier in (21) above that the form have can cliticise onto an immediately adjacent pronoun ending in a vowel/diphthong which asymmetrically c-commands have.

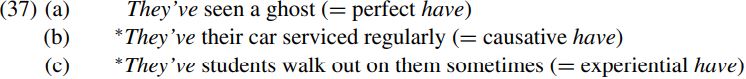

In the light of this, consider contrasts such as the following:

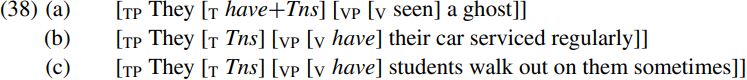

How can we account for this contrast? If we assume that perfect have in (37a) is a finite (present-tense) auxiliary which occupies the head T position of TP, but that causative have in (37b) and experiential have in (37c) are main verbs occupying the head V position of a VP complement of a null T, then prior to cliticisation the three clauses will have the respective simplified structures indicated by the partial labelled bracketings in (38a–c) below (where Tns is an abstract tense affix):

(Here and throughout these topics, partial labelled bracketings are used to show those parts of the structure most relevant to the discussion at hand, omitting other parts. In such cases, we generally show relevant heads and their maximal projections but omit intermediate projections, as in (38) above where we show T and TP but not T-bar.) Since we claimed in (21) above that cliticisation of have onto a pronoun is blocked by the presence of an intervening constituent, it should be obvious why have can cliticise onto they in (38a) but not in (38b,c): after all, there is no intervening constituent separating the pronoun they from have in (38a), but they is separated from the verb have in (38b,c) by an intervening T constituent containing a tense affix (Tns), so blocking contraction. It goes without saying that a crucial premise of this account is the assumption that (in its finite forms) have is positioned in the head T position of TP in its use as a perfect auxiliary, but in the head V position of VP in its use as a causative or experiential verb. In other words, have cliticisation facts suggest that finite clauses which lack a finite auxiliary are TPs headed by an abstract T constituent containing a tense affix.

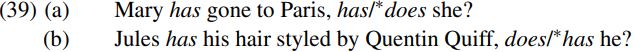

A further piece of empirical evidence in support of the TP analysis comes from tag questions. As we see from the examples below, sentences containing (a finite form of) perfect have are tagged by have, whereas sentences containing (a finite form of) causative have are tagged by do:

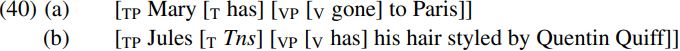

Given the T-analysis of perfect have and the V-analysis of causative have and the assumption that all clauses contain a TP constituent, the main clauses in (39a,b) will have the respective (simplified) structures indicated in (40a,b) below:

(A complication which we overlook here and throughout is that HAVE will only be spelled out as the form has in the PF component, and hence should more properly be represented as the abstract item HAVE in the syntax.) If we assume that the T constituent which appears in the tag must be a copy of the T constituent in the main clause, the contrast in (39) can be accounted for in a principled fashion. In (39a), the head T position of TP is filled by the auxiliary has, and so the tag contains a copy of has. In (39b), however, T contains only an abstract tense affix, hence we would expect the tag to contain a copy of this affix. Now, in the main clause, the affix can be lowered from T onto the verb have in the head V position of VP, with the resulting verb eventually being spelled out as has. But in the tag, there is no verb for the affix to be lowered onto. Accordingly, DO-support is used: in other words, the (meaningless) dummy auxiliary stem do is attached to the affix in order to provide an overt verbal stem for the affix to attach to. The lexical entry for the irregular verb DO specifies that the string [do+ Tns] is spelled out as does when the tense affix carries the features [third-person, singular-number, present-tense].

We have argued that a finite T always contains a tense affix. In clauses containing an auxiliary, the auxiliary is directly merged with the tense affix to form an auxiliary+ affix structure; in auxiliariless clauses, the tense affix is lowered onto the main verb by an Affix Hopping operation in the PF component, so forming a verb+ affix structure. However, in order to avoid our exposition becoming too abstract, we will generally show auxiliaries and verbs in their orthographic form – as indeed we did in (40) above, where the relevant form of the word HAVE was represented as has rather than as  .

.

|

|

|

|

دراسة: حفنة من الجوز يوميا تحميك من سرطان القولون

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

تنشيط أول مفاعل ملح منصهر يستعمل الثوريوم في العالم.. سباق "الأرنب والسلحفاة"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

الطلبة المشاركون: مسابقة فنِّ الخطابة تمثل فرصة للتنافس الإبداعي وتنمية المهارات

|

|

|