Clauses

Having considered how phrases are formed, let’s now turn to look at how clauses and sentences are formed. By way of illustration, suppose that speaker B had used the simple (single-clause) sentence italicized in (14) below to reply to speaker A, rather than the phrase used by speaker B in (10):

What’s the structure of the italicized clause produced by speaker B in (14)?

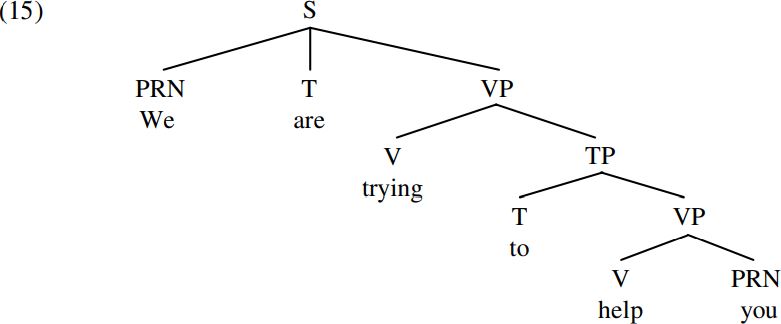

In work in the 1960s, clauses were generally taken to belong to the category S (Sentence/Clause), and the sentence produced by B in (14) would have been taken to have a structure along the following lines:

However, a structure such as (15) violates the two constituent structure principles which we posited in (12) and (13) above. More particularly, the S analysis of clauses in (15) violates the Headedness Principle (12) in that the S we are trying to help you is a structure which has no head of any kind. Likewise, the S analysis in (15) also violates the Binarity Principle (13) in that the S constituent We are trying to help you is not binary-branching but rather ternary-branching, because it branches into three immediate constituents, namely the PRN we, the T are, and the VP trying to help you. If our theory of Universal Grammar requires every syntactic structure to be a binary-branching projection of a head word, it is clear that we have to reject the S-analysis of clause structure in (15) as one which is not in keeping with UG principles.

Let’s therefore explore an alternative analysis of the structure of clauses which is consistent with the headedness and binarity requirements in (12) and (13). More specifically, let’s make the unifying assumption that clauses are formed by the same binary merger operation as phrases, and accordingly suppose that the italicized clause in (14B) is formed by merging the (present) tense auxiliary are with the verb phrase trying to help you, and then subsequently merging the resulting expression are trying to help you with the pronoun we. Since are belongs to the category T of tense auxiliary, it might at first sight seem as if merging are with the verb phrase trying to help you will derive (i.e. form) the tense projection/tense phrase/TP are trying to help you. But this can’t be right, since it would provide us with no obvious account of why speaker B’s reply in (16) below is ungrammatical:

If are trying to help you is a TP (i.e. a complete tense projection), how come it can’t be used to answer speaker A’s question in (16), since we see from sentences like (6B) that TP constituents like to help you can be used to answer questions.

An informal answer we can give is to say that the expression are trying to help you is somehow ‘incomplete’, and that only ‘complete’ expressions can be used to answer questions. In what sense is Are trying to help you incomplete? The answer is that finite T constituents require a subject, and the finite auxiliary are doesn’t have a subject in (16). More specifically, let’s assume that when we merge a tense auxiliary (= T) with a verb phrase (= VP), we form an intermediate projection which we shall here denote as  (pronounced ‘tee-bar’); and that only when we merge the relevant T-bar constituent with a subject like we do we form a maximal projection – or, more informally a ‘complete TP’. Given these assumptions, the italicized clause in (14B) will have the structure (17) below:

(pronounced ‘tee-bar’); and that only when we merge the relevant T-bar constituent with a subject like we do we form a maximal projection – or, more informally a ‘complete TP’. Given these assumptions, the italicized clause in (14B) will have the structure (17) below:

What this means is that a tense auxiliary like are has two projections: a smaller intermediate projection  formed by merging are with its complement trying to help you to form the T-bar (intermediate tense projection) are trying to help you; and a larger maximal projection (TP) formed by merging the resulting

formed by merging are with its complement trying to help you to form the T-bar (intermediate tense projection) are trying to help you; and a larger maximal projection (TP) formed by merging the resulting  are trying to help you with its subject we to form the TP We are trying to help you. Saying that TP is the maximal projection of are in (17) means that it is the largest constituent headed by the tense auxiliary are.

are trying to help you with its subject we to form the TP We are trying to help you. Saying that TP is the maximal projection of are in (17) means that it is the largest constituent headed by the tense auxiliary are.

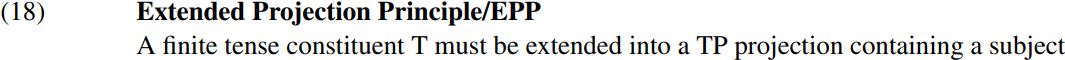

Why should tense auxiliaries require two different projections, one in which they merge with a following complement to form a T-bar, and another in which the resulting T-bar merges with a preceding subject to form a TP? Following a suggestion made by Chomsky (1982, p. 10), the requirement for auxiliaries to have two projections (as in (17) above) was taken in earlier work to be a consequence of a principle of Universal Grammar known as the Extended Projection Principle (conventionally abbreviated to EPP), which can be outlined informally as follows:

Given that the grammatical properties of words are described in terms of sets of grammatical features, we can say that tense auxiliaries like are carry an [EPP] feature which requires them to have an extended projection into a TP which has a subject. If we posit that all tense auxiliaries carry an [EPP] feature, it follows that any structure (like that produced by speaker B in (16) above) containing a tense auxiliary which does not have a subject will be ungrammatical by virtue of violating the Extended Projection Principle (18).

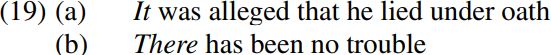

The EPP requirement (for a finite auxiliary to have a subject) would seem to be essentially syntactic (rather than semantic) in nature, as we can see from sentences such as (19) below:

The EPP requirement (for a finite auxiliary to have a subject) would seem to be essentially syntactic (rather than semantic) in nature, as we can see from sentences such as (19) below:

In structures like (19), the italicized subject pronouns it/there seem to have no semantic content (in particular, no referential properties) of their own, as we see from the fact that neither can be questioned by the corresponding interrogative words what?/where? (cf. the ungrammaticality of ∗What was alleged that he lied under oath? and ∗Where has been no trouble?), and neither can receive contrastive focus (hence it/there cannot be contrastively stressed in sentences like (19) above). Rather, they function as expletive pronouns – i.e. pronouns with no intrinsic meaning which are used in order to satisfy the syntactic Projection Principle/EPP. For example, the expletive subject it in (19a) might be argued to serve the syntactic function of providing a subject for the auxiliary was to agree with in person and number.

It is interesting to note that theoretical considerations also favor a binary-branching TP analysis of clause structure like (17) over a ternary-branching S analysis like (15). The essential spirit of Minimalism is to reduce the theoretical apparatus which we use to describe syntactic structure to a minimum. For example, it has been suggested (e.g. by Kayne 1994, Yang 1999 and Chomsky 2001) that tree diagrams should only contain information about hierarchical structure (i.e. containment/constituent structure relations), not about linear structure (i.e. left-to-right word order), because linear information is redundant (in the sense that it can be predicted from hierarchical structure by simple word-order rules) if we use binary-branching trees. Suppose for example that we have a word-order rule for English to the effect that ‘Any constituent of a phrase HP which is the sister of the head H is positioned to the right of H, but any other constituent of HP is positioned to the left of H.’ This word-order rule will correctly predict (inter alia) that the VP trying to help you in (17) must be positioned to the right of the tense auxiliary/T are (because the relevant VP is the sister of are), and that the pronoun we must be positioned to the left of are (because we is not the sister of are). As you can see for yourself, it’s not clear how we can achieve the same result (of eliminating redundant word-order information from trees) under a ternary-branching analysis like (15), since both the pronoun we and the verb phrase trying to help you are sisters of are in (15). It should be noted in passing that an important consequence of assuming that linear order is not a syntactic relation is that it entails that syntactic operations cannot be sensitive to word order (e.g. we can’t handle subject–auxiliary agreement by saying that a finite auxiliary agrees with a preceding noun or pronoun expression): rather, all syntactic operations must be sensitive to hierarchical rather than linear structure. How this works in practice will become clearer as our exposition unfolds.

A question which we have not so far asked about the structure of clauses concerns what role is played by complementizers like that, for and if, e.g. in speaker B’s reply in (20) below:

Where does the C/complementizer that fit into the structure of the sentence? The answer suggested in work in the 1970s was that a complementizer merges with an S constituent like that in (15) above to form an  (pronounced ‘ess-bar’) constituent like that shown below (simplified by not showing the internal structure of the VP trying to help you, which is as in (11) above):

(pronounced ‘ess-bar’) constituent like that shown below (simplified by not showing the internal structure of the VP trying to help you, which is as in (11) above):

However, the claim that a clause introduced by a complementizer has the status of an S-bar constituent falls foul of the Headedness Principle (12), which requires that every syntactic structure be a projection of a head word. The principle is violated because S-bar in (21) is analyzed as a projection of the S constituent we are trying to help you, and S is clearly not a word (but rather a string of words).

An interesting way round the headedness problem is to suppose that the head of a clausal structure introduced by a complementizer is the complementizer itself: since this is a single word, there would then be no violation of the Headedness Principle (12) requiring every syntactic structure to be a projection of a head word. Let’s therefore assume that the complementizer that merges with the TP we are trying to help you (whose structure is shown in (17) above) to form the CP/complementizer projection/complementizer phrase in (22) below:

(22) tells us that the complementizer that is the head of the overall clause that we are trying to help you (and conversely, the overall clause is a projection of that) – and indeed this is implicit in the traditional description of such structures as that-clauses. (22) also tells us that the complement of that is the TP/tense phrase we are trying to help you. Clauses introduced by complementizers have been taken to have the status of CP/complementizer phrase constituents since the pioneering work of Stowell (1981) and Chomsky (1986b).

(22) tells us that the complementizer that is the head of the overall clause that we are trying to help you (and conversely, the overall clause is a projection of that) – and indeed this is implicit in the traditional description of such structures as that-clauses. (22) also tells us that the complement of that is the TP/tense phrase we are trying to help you. Clauses introduced by complementizers have been taken to have the status of CP/complementizer phrase constituents since the pioneering work of Stowell (1981) and Chomsky (1986b).

An interesting aspect of the analyses in (17) and (22) above is that clauses and sentences are analyzed as headed structures – i.e. as projections of head words (in conformity with the Headedness Principle). In other words, just as phrases are projections of a head word (e.g. a verb phrase like help you is a projection of the verb help), so too a sentence like We will help you is a projection of the auxiliary will, and a complement clause like the bracketed that-clause in I can’t promise [that we will help you] is a projection of the complementizer that. This enables us to arrive at a unitary analysis of the structure of phrases, clauses and sentences, in that clauses and sentences (like phrases) are projections of head words. More generally, it leads us to the conclusion that clauses/sentences are simply particular kinds of phrases (e.g. a that-clause is a complementizer phrase).

An assumption which is implicit in the analyses which we have presented here is that phrases and sentences are derived (i.e. formed) in a bottom-up fashion (i.e. they are built up from bottom to top). For example, the clause in (22) involves the following sequence of merger operations: (i) the verb help is merged with the pronoun you to form the VP help you; (ii) the resulting VP is merged with the non-finite T/tense particle to to form the TP to help you; (iii) this TP is in turn merged with the verb trying to form the VP trying to help you; (iv) the resulting VP is merged with the T/tense auxiliary are to form the T-bar are trying to help you; (v) this T-bar is merged with its subject we to form the TP we are trying to help you; and (vi) the resulting TP is in turn merged with the C/complementizer that to form the CP structure (22) that we are trying to help you. By saying that the structure (22) is derived in a bottom-up fashion, we mean that lower parts of the structure nearer the bottom of the tree are formed before higher parts of the structure nearer the top of the tree. (An alternative top-down model is presented in Phillips 2003.)

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة