Complementisers

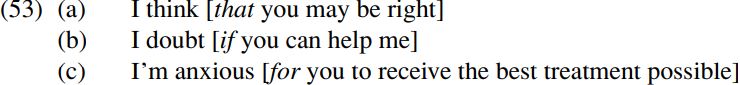

The last type of functional category which we shall look here is that of complementiser (abbreviated to COMP in earlier work and to C in more recent work): this is a term employed to describe the kind of (italicized) word which is used to introduce complement clauses such as those bracketed below:

Each of the bracketed clauses in (53) is a complement clause, in that it functions as the complement of the word immediately preceding it (think/doubt/anxious); the italicized word which introduces each clause is known in work since 1970 as a complementizer (but was known in more traditional work as a particular type of subordinating conjunction).

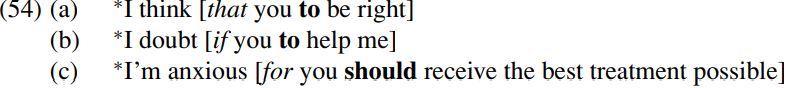

Complementizers are functors in the sense that they encode particular sets of grammatical properties. For example, complementizers encode (non-)finiteness by virtue of the fact that they are intrinsically finite or non-finite. More specifically, the complementizers that and if are inherently finite in the sense that they can only be used to introduce a finite clause (i.e. a clause containing a present- or past-tense auxiliary or verb), and not e.g. an infinitival to-clause; by contrast, for is an inherently infinitival complementizer, and so can be used to introduce a clause containing infinitival to, but not a finite clause containing a tensed auxiliary like (past-tense) should; compare the examples in (53) above with those in (54) below:

(54a,b) are ungrammatical because that/if are finite complementizers and so cannot introduce an infinitival to clause; (54c) is ungrammatical because for is an infinitival complementizer and so cannot introduce a finite clause containing a past-tense auxiliary like should.

Complementizers in structures like (53) serve three grammatical functions. Firstly, they mark the fact that the clause they introduce is an embedded clause (i.e. a clause which is contained within another expression – in this case, within a main clause containing think/doubt/anxious). Secondly, they serve to indicate whether the clause they introduce is finite or non-finite (i.e. denotes an event taking place at a specified or unspecified time): that and if serve to introduce finite clauses, while for introduces non-finite (more specifically, infinitival) clauses. Thirdly, complementizers mark the force of the clause they introduce: typically, if introduces an interrogative (i.e. question-asking) clause, that introduces a declarative (statement-making) clause and for introduces an irrealis clause (i.e. a clause denoting an ‘unreal’ or hypothetical event which hasn’t yet happened and may never happen).

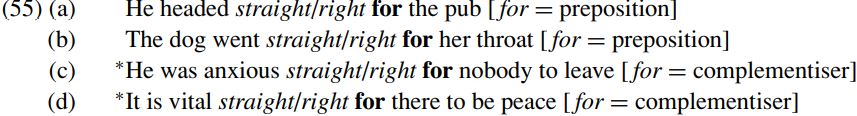

However, an important question to ask is whether we really need to assign words such as for/that/if (in the relevant function) to a new category of C/complementizer, or whether we couldn’t simply treat (e.g.) for as a preposition, that as a determiner and if as an adverb. The answer is ‘No’, because there are significant differences between complementizers and other apparently similar words. For example, one difference between the complementizer for and the preposition for is that the preposition for has substantive lexical semantic content and so (in some but not all of its uses) can be intensified by straight/right, whereas the complementizer for is a functor and can never be so intensified:

Moreover, the preposition for and the complementizer for also differ in their syntactic behavior. For example, a clause introduced by the complementizer for can be the subject of an expression like would cause chaos, whereas a phrase introduced by the preposition for cannot:

Moreover, the preposition for and the complementizer for also differ in their syntactic behavior. For example, a clause introduced by the complementizer for can be the subject of an expression like would cause chaos, whereas a phrase introduced by the preposition for cannot:

What makes it even more implausible to analyze infinitival for as a preposition is the fact that (bold-printed) prepositions in English aren’t generally followed by a [bracketed] infinitive complement, as we see from the ungrammaticality of:

On the contrary, as examples such as (46) above illustrate, the only verbal complements which can be used after prepositions are gerund structures containing a verb in the -ing form.

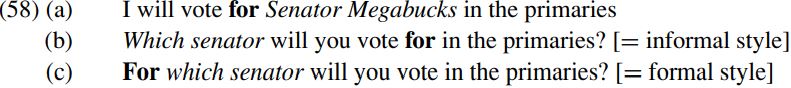

A further difference between the complementizer for and the preposition for is that the noun or pronoun expression following the preposition for (or a substitute interrogative expression like who?/what?/which one?) can be preposed to the front of the sentence (with or without for) if for is a preposition, but not if for is a complementizer. For example, in (58) below, for functions as a preposition and the (distinguished) nominal Senator Megabucks functions as its complement, so that if we replace Senator Megabucks by which senator? the wh-expression can be preposed either on its own (in informal styles of English) or together with the preposition for (in formal styles):

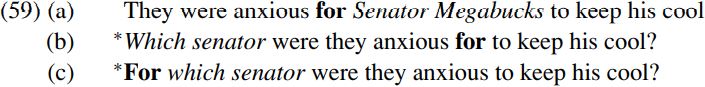

However, in (59a) below, the italicized expression is not the complement of the complementizer for(the complement of for in (59a) is the infinitival clause Senator Megabucks to keep his cool), but rather is the subject of the expression to keep his cool; hence, even if we replace Senator Megabucks by the interrogative wh-phrase which senator, the wh-expression can’t be preposed (with or without for):

Furthermore, when for functions as a complementizer, the whole for-clause which it introduces can often (though not always) be substituted by a clause introduced by another complementizer; for example, the italicized for-clause in (60a) below can be replaced by the italicized that-clause in (60b):

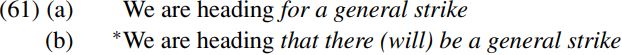

By contrast, the italicized for-phrase in (61a) below cannot be replaced by a that-clause, as we see from the ungrammaticality of (61b):

So, there is considerable evidence in favor of drawing a categorial distinction between the preposition for and the complementizer for: they are different lexical items (i.e. words) belonging to different categories.

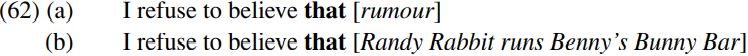

Consider now the question of whether the complementizer that could be analyzed as a determiner. At first sight, it might seem as if such an analysis could provide a straightforward way of capturing the apparent parallelism between the two uses of that in sentences such as the following:

Given that the word that has the status of a prenominal determiner in sentences such as (62a), we might suppose that it has the function of a preclausal determiner (i.e. a determiner introducing the following italicized clause Randy Rabbit runs Benny’s Bunny Bar) in sentences such as (62b).

However, there is evidence against a determiner analysis of the complementizer that. Part of this is phonological in nature. In its use as a complementizer (in sentences such as (62b) above), that typically has the reduced form /ðət/, whereas in its use as a determiner (e.g. in sentences such as (62a) above), that invariably has the unreduced form /ðæt/: the phonological differences between the two suggest that we are dealing with two different lexical items here (i.e. two different words), one of which functions as a complementizer and typically has a reduced vowel, the other of which functions as a determiner and always has an unreduced vowel.

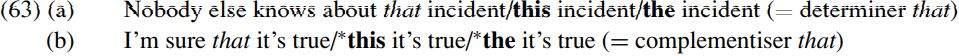

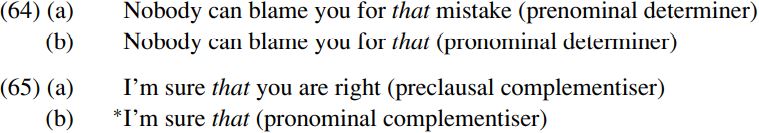

Moreover, that in its use as a determiner (though not in its use as a complementizer) can be substituted by another determiner (such as this/the):

Similarly, the determiner that can be used pronominally (without any complement), whereas the complementizer that cannot:

Similarly, the determiner that can be used pronominally (without any complement), whereas the complementizer that cannot:

The clear phonological and syntactic differences between the two argue that the word that which serves to introduce complement clauses is a different item (belonging to the category C/complementizer) from the determiner/D that which modifies noun expressions.

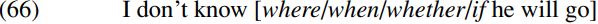

The third item which we earlier suggested might function as a complementizer in English is interrogative if. However, at first sight, it might seem as if there is a potential parallelism between if and interrogative wh-adverbs like when/where/whether, since they appear to occupy the same position in sentences like:

Hence we might be tempted to analyze if as an interrogative adverb.

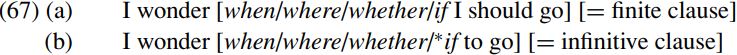

However, there are a number of reasons for rejecting this possibility. For one thing, if differs from interrogative adverbs like where/when/whether not only in its form (it isn’t a wh-word, as we can see from the fact that it doesn’t begin with wh), but also in the range of syntactic positions it can occupy. For example, whereas typical wh-adverbs can occur in finite and infinitive clauses alike, the complementizer if is restricted to introducing finite clauses:

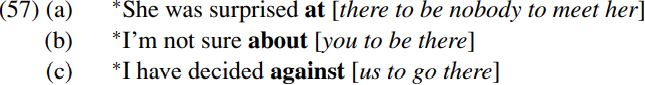

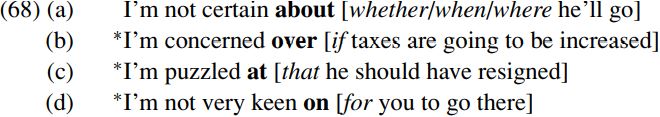

Moreover, if is different from interrogative wh-adverbs (but similar to other complementizers) in that it cannot be used to introduce a clause which serves as the complement of a (bold-printed) preposition:

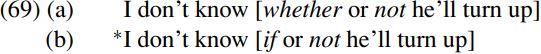

Finally, whereas a wh-adverb can typically be coordinated with (e.g. joined by a coordinating conjunction like and/or to) the adverb not, this is not true of if:

For reasons such as these, it seems more appropriate to categorise if as an interrogative complementiser, and whether/where/when as interrogative adverbs. More generally, our discussion highlights the need to posit a category C of complementizer, to designate clause-introducing items such as if/that/for which serve the function of introducing specific types of finite or infinitival clause.

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة