Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Auxiliaries

المؤلف:

Andrew Radford

المصدر:

Minimalist Syntax

الجزء والصفحة:

47-2

2-8-2022

2027

Auxiliaries

Having looked at the nominal functional category pronoun, we now turn to look at the verbal functional category auxiliary. Traditional grammarians use this term to denote a special class of items which once functioned simply as verbs, but in the course of the evolution of the English language have become sufficiently distinct from main verbs that they are now regarded as belonging to a different category of auxiliary (conventionally abbreviated to AUX).

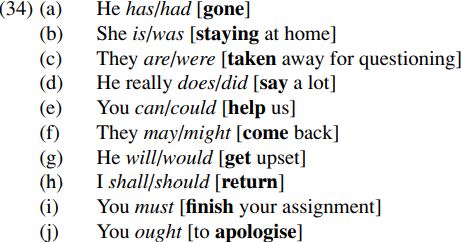

Auxiliaries differ from main verbs in a number of ways. Whereas a typical main verb like want may take a range of different types of complement (e.g. an infinitival to-complement as in I want [(you) to go home], or a noun expression as in I want [lots of money]), by contrast auxiliaries typically allow only a verb expression as their complement, and have the semantic function of marking grammatical properties associated with the relevant verb, such as tense, aspect, voice, or mood. The items italicized in (34) below (in the use illustrated there) are traditionally categorized as auxiliaries taking a [bracketed] complement containing a bold-printed non-finite verb:

In the uses illustrated here, have/be in (34a,b) are (perfect/progressive) aspect auxiliaries, be in (34c) is a (passive) voice auxiliary, do in (34d) a (present/past) tense auxiliary, and can/could/may/might/will/would/shall/should/must/ought in (34e–j) modal auxiliaries. As will be apparent, ought differs from other modal auxiliaries like should which take an infinitive complement in requiring use of infinitival to.

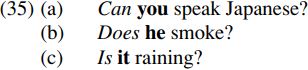

There are clear syntactic differences between auxiliaries and verbs. For example (as we saw in §1.5), auxiliaries can undergo inversion (and thereby be moved into pre-subject position) in questions such as (35) below, where the inverted auxiliary is italicized and the subject is bold-printed:

By contrast, typical verbs do not themselves permit inversion, but rather require what is traditionally called do-support (i.e. they have inverted forms which require the use of the auxiliary do):

A second difference between auxiliaries and verbs is that auxiliaries can generally be directly negated by a following not (which can usually attach to the auxiliary in the guise of its contracted form n’t):

By contrast, verbs cannot themselves be directly negated by not/n’t, but require indirect negation through the use of do-support:

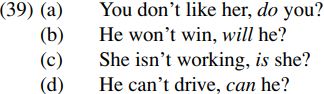

(Note that in structures such as John decided not to stay the negative particle not negates the infinitive complement to stay rather than the verb decided, as we see from the fact that the sentence can be paraphrased as ‘John decided that he would not stay’, not as ‘John did not decide that he would stay.’) And thirdly, auxiliaries can appear in sentence-final tags, as illustrated by the examples below (where the part of the sentence following the comma is traditionally referred to as a tag):

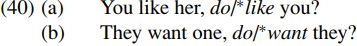

In contrast, verbs can’t themselves be used in tags, but rather require the use of do-tags:

So, on the basis of these (and other) syntactic properties, we can conclude that auxiliaries constitute a different category from verbs.

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)