Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Tonal mobility

المؤلف:

David Odden

المصدر:

Introducing Phonology

الجزء والصفحة:

303-9

14-4-2022

1646

Tonal mobility

The final demonstration of the autonomy of tone from segments is the tone mobility, which is the fact that tones can move about from vowel to vowel quite easily, in a fashion not shared with segmental properties. One example of tonal mobility comes from Nkore, seen in (63). This language has an underlying contrast between words whose last syllable is H toned, and those whose penultimate syllable is H toned. In prepausal position, underlyingly final H tones shift to the penultimate syllable, thus neutralizing with nouns having an underlyingly penult H. When some word follows the noun, the underlying position of the H tone is clearly revealed.

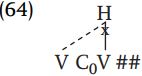

There are a number of reasons internal to the grammar of Nkore for treating L tone as the default tone, and for only specifying H tones in the phonology so that phonetically L-toned vowels are actually toneless. This alternation can be accounted for by the following rule of tonethrowback.

Another example of tone shift can be seen in Kikuyu. Like Nkore, there are good reasons to analyze this language phonologically solely in terms of the position of H tones, with vowels not otherwise specified as H being realized phonetically with a default L tone. We will follow the convention adopted in such cases as marking H-toned vowels with an acute accent, and not marking toneless (default L) vowels.

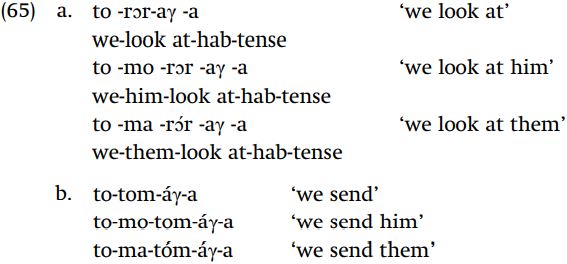

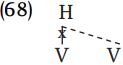

Consider the Kikuyu data in (65), illustrating the current habitual tense. The first two examples in (65a) would indicate that the morphemes to-, -rɔr-, -aγ-, and -a are all toneless. The third example, however, shows the root rɔr with an H tone: this happens only when the root is preceded by the object prefix ma. In (65b), we see that – in contrast to what we see in (65a) – the habitual suffix -aγ- has an H tone when it is preceded by the root tom (which is itself toneless on the surface). As with (65a), the syllable that follows ma has an H tone.

It is clear, then, that certain syllables have the property of causing the following syllable to have a surface H tone. This is further demonstrated in (66), where the derivational suffixes -er- and -an- follow the roots -rɔr-and -tom-: we can see that the syllable after -tom always receives an H tone.

Further examples of this phenomenon are seen in the examples of the recent past in (67). In (67a), the root rɔr (which generally has no H tone) has an H tone when it stands immediately after the recent-past-tense prefix -a-; or, the object prefix that follows -a- will have a surface H tone. The examples in (67b) show the same thing with the root –tom-which we have seen has the property of assigning an H tone to the following vowel.

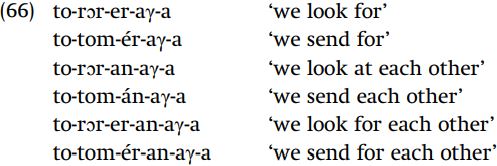

We would assume that the root -tóm- has an H, as do the object prefix –má-and the tense prefix -a-, and this H tone is subject to the following rule of tone shift, which moves every H tone one vowel to the right.

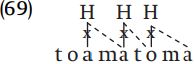

Thus, /to-tóm-er-aγ-a/ becomes totoméraγa, /to-má-rɔr-aγ-a/ becomes tomarɔ́ - raγa, and /to-á-má-tóm-a/ becomes toamátómá.

An even more dramatic example of tone shifting comes from Digo. In this language, the last H tone of a word shifts to the end of the word. The root vugura is toneless, as is the object prefix ni, but the object prefix a ‘them’ has an underlying H tone, which is phonetically realized on the last vowel of the word. Similarly, the root togora is toneless, as is the subject prefix ni, but the third-singular subject prefix a has an H tone, which shifts to the end of the word. Lastly, the root t s ukura is toneless, as is the tense-aspect prefix -na-, but the perfective prefix ka has an H tone which shifts to the last vowel of the word.

These data can be accounted for by a rule of tone shift which is essentially the same as the Kikuyu rule, differing only in that the tone shifts all the way to the end of the word.

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)