Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Yawelmani /u:/

المؤلف:

David Odden

المصدر:

Introducing Phonology

الجزء والصفحة:

257-8

9-4-2022

1516

Yawelmani /u:/

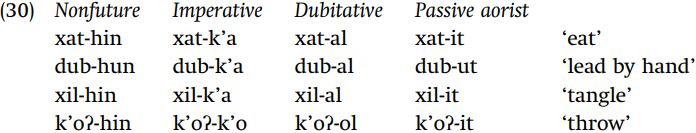

Aspects of Yawelmani have been discussed. Two of the most important processes are vowel harmony and vowel shortening. The examples in (30) demonstrate the basics of vowel harmony: a suffix vowel becomes rounded if it is preceded by a round vowel of the same height.

Thus the root vowel /o/ has no effect on the suffixes /hin/ and /it/ but causes rounding of /k’a/ and /al/ — and the converse holds of the vowel /u/

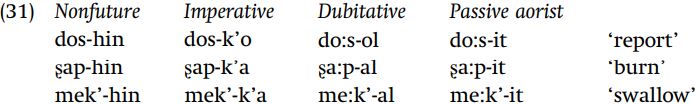

The data in (31) show that long vowels cannot appear before two consonants. These stems have underlying long vowels and, when followed by a consonant-initial affix, the vowel shortens.

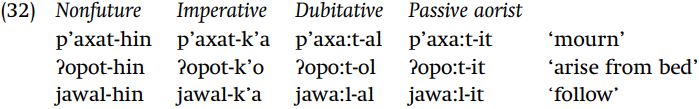

Another class of verb roots has the surface pattern CVCV:C – the peculiar fact about these roots is that the first vowel is always a short version of the second vowel.

In [wo:ʔuj-hun], [do:lul-hun], the second vowel is epenthetic, so these roots underlyingly have the shape CV:CC, parallel to [ʔa:mil-hin] ~ [ʔamlal] ‘help.’

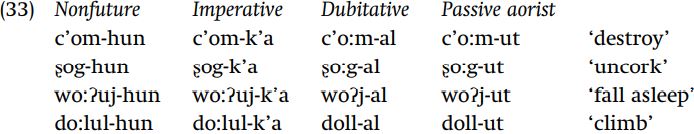

There are problematic roots in (33). Although the stem vowel is a mid vowel, a following nonhigh vowel does not harmonize – they seem to be exceptions. Worse, a high vowel does harmonize with the root vowel, even though it does not even satisfy the basic phonological requirement for harmony (the vowels must be of the same height).

A noteworthy property of such roots is that their vowels are always long.

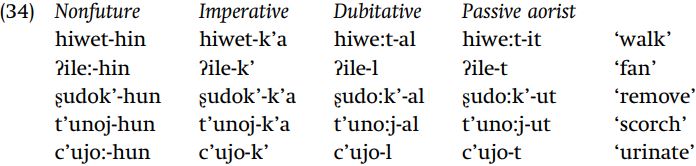

There is another irregularity connected with certain surface mid vowels. The data in (34) illustrate a set of CVCVV(C) roots, where, as we noticed before, the two vowels are otherwise identical. In these verbs, the second long vowel is a nonhigh version of the first vowel.

The surface mid vowels of these stems act irregularly for harmony – they do not trigger harmony in mid vowels, so they do not act like other mid vowels. They also exceptionally trigger harmony in high vowels, as only high vowels otherwise do.

When you consider the vowels of Yawelmani – [i e a o u e: o: a:] – you see that long high vowels are lacking in the language. The preceding mysteries are solved if you assume, for instance, that the underlying stem of the verb ‘scorch’ is /tunu:j/. As such, the root would obey the canonical restriction on the vowels of a bivocalic stem – they are the same vowel – and you expect /u:/ to trigger harmony on high vowels but not on mid vowels, as is the case. A subsequent rule lowers /u:/ to [o:], merging the distinction between underlying /o:/ and /u:/.

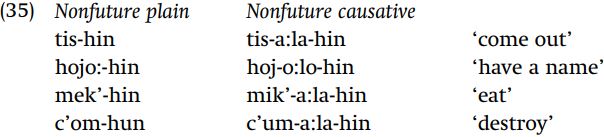

The assumption that /u:/ becomes [o:] and therefore some instances of [o:] derive from /u:/ explains other puzzling alternations. There is a vowel-shortening process which applies in certain morphological contexts. One context is the causative, which adds the suffix -a:la and shortens the preceding stem vowel.

We have seen in (33) that the root [c’o:m] has the phonological characteristics of an abstract vowel, so given the surface-irregular pattern of vowel harmony in c’om-hun, c’om-k’a we can see that the underlying vowel must be a high vowel. The fact that the vowel actually shows up as a high vowel as a result of the morphologically conditioned shortening rule gives further support to the hypothesized abstract underlying vowel.

The approach which Kiparsky advocates for absolute neutralization does not work for Yawelmani: these words are not exceptions. Being an exception has a specific meaning, that a given morpheme fails to undergo or trigger a rule which it otherwise would undergo. The fact that vowel harmony does not apply in c’o:m-al can be treated as exceptionality. But this root does actually trigger vowel harmony, as shown by c’o:m-ut, and such application is problematic since the rule is applying when the formal conditions of the rule are not even satisfied on the surface. Marking a root as an exception says that although the root would be expected to undergo a rule, it simply fails to undergo the rule. What we have in Yawelmani is something different – a form is triggering a rule even though it should not. The exceptionality analysis also offers no account of stems such as c’ujo:-hun, where the first vowel should have been a copy of the second vowel but instead shows up as a high vowel; nor does the exceptionality account have any way to explain why the “exceptional” roots show up with high vowels when the root is subject to morphological vowel shortening as in c’om-hun ~ c’um-a:la-hin.

Although the specific segment /u:/ is not pronounced as such in the language, concern over the fact that pronunciations do not include that particular segment would be misguided from the generative perspective, which holds that language sounds are defined in terms of features and the primary unit of representation is the feature, not the segment. All of the features comprising /u:/ – vowel height, roundness, length – are observed in the surface manifestations of the abstract vowels.

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)