Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Assimilations

المؤلف:

David Odden

المصدر:

Introducing Phonology

الجزء والصفحة:

208-7

7-4-2022

6816

Assimilations

The most common phonological process in language is assimilation, where two segments become more alike by having one segment take on values for one or more features from a neighboring segment.

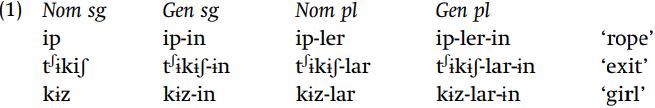

Vowel harmony. An example of assimilation is vowel harmony, and the archetypical example of vowel harmony is the front–back vowel harmony process of Turkish. In this language, vowels within a word are (generally) all front, or all back, and suffixes alternate according to the frontness of the preceding vowel. The genitive suffix accordingly varies between -in and -ɨn, as does the plural suffix lar ~ ler.

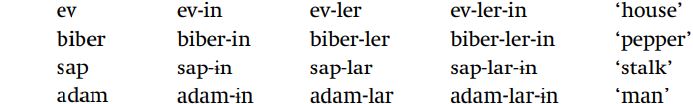

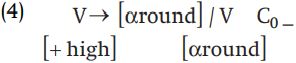

This process can be stated formally as (2).

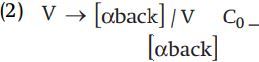

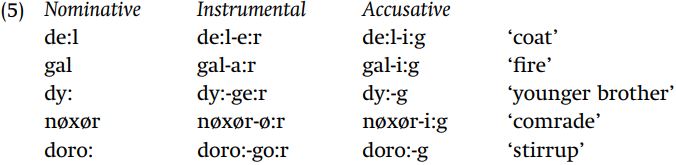

A second kind of vowel harmony found in Turkish is rounding harmony. In Turkish, a rule assimilates any high vowel to the roundness of the preceding vowel. Consider the following data, involving stems which end in round vowels:

The genitive suffix which has a high vowel becomes rounded when the preceding vowel is round, but the plural suffix which has a nonhigh vowel does not assimilate in roundness. Thus the data in (3) can be accounted for by the following rule.

A problem that arises in many vowel harmony systems is that it is difficult if not impossible to be certain what the underlying vowel of the suffix is. For the plural suffix, we can surmise that the underlying vowel is nonround, since it is never phonetically round, so the most probable hypotheses are /a/ or /e/. For the genitive suffix, any of /i, ɨ, y, u/ would be plausible, since from any of these vowels, the correct output would result by applying these rules.

It is sometimes assumed that, if all other factors are the same for selecting between competing hypotheses about the underlying form, a less marked (crosslinguistically frequent) segment should be selected over a more marked segment. By that reasoning, you might narrow the choice to /i, u/ since ɨ, y are significantly more marked than /i, u/. The same reasoning might lead you to specifically conclude that alternating high vowels are /i/, on the assumption that i is less marked than u: however, that conclusion regarding markedness is not certain. The validity of invoking segmental markedness for chosing underlying forms is a theoretical assumption, and does not have clear empirical support. A further solution to the problem of picking between underlying forms is that [+high] suffix vowels in Turkish are not specified at all for backness or roundness, and thus could be represented with the symbol /I/, which is not an actual and pronounceable vowel, but represents a so-called archiphoneme having the properties of being a vowel and being high, but being indeterminate for the properties [round] and [back]. There are a number of theoretical issues which surround the possibility of having partially specified segments, which we will not go into here.

Mongolian also has rounding harmony: in this language, only nonhigh vowels undergo the assimilation, and only nonhigh vowels trigger the process.

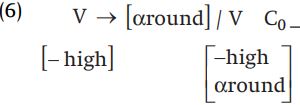

This rule can be forumlated as in (6).

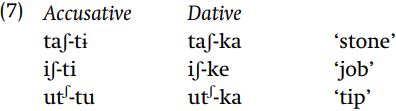

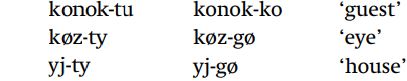

Typological research has revealed a considerable range of variation in the conditions that can be put on a rounding harmony rule. In Sakha, high vowels assimilate in roundness to round high and nonhigh vowels (cf.: aγa-lɨɨn ‘father (associative),’ sep-tiin ‘tool (associative)’ vs. oγo-luun ‘child (associative),’ børø-lyyn ‘wolf (associative),’ tynnyktyyn ‘window (associative)’), but nonhigh vowels only assimilate in roundness to a preceding nonhigh vowel (cf. aγa-lar ‘fathers,’ sep-ter ‘tools,’ tynnyk-ter ‘windows,’ kus-tar ‘ducks’ vs. oγo-lor ‘children,’ børø-lør ‘wolves’). In Yawelmani, vowels assimilate rounding from a preceding vowel of the same height (thus, high vowels assimilate to high vowels, low vowels assimilate to low vowels). As seen in (7), Kirghiz vowels generally assimilate in roundness to any preceding vowel except that a nonhigh vowel does not assimilate to a back high round vowel (though it will assimilate rounding from a front high round vowel).

This survey raises the question whether you might find a language where roundness harmony only takes place between vowels of different heights rather than the same height, as we have seen. Although such examples are not known to exist, we must be cautious about inferring too much from that fact, since the vast majority of languages with rounding harmony are genetically or areally related (Mongolian, Kirghiz, Turkish, Sakha). The existence of these kinds of rounding harmony means that phonological theory must provide the tools to describe them: what we do not know is whether other types of rounding harmony also exist. Nor is it safe, given our limited database on variation within rounding harmony systems, to make very strong pronouncements about what constitutes “common” versus “rare” patterns of rounding harmony.

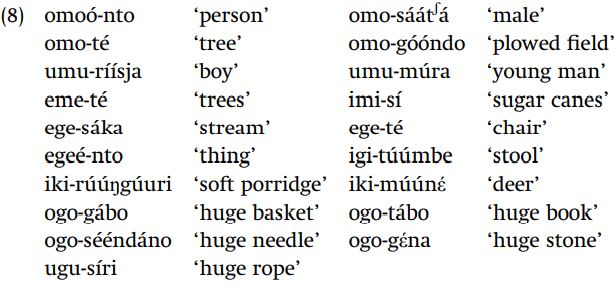

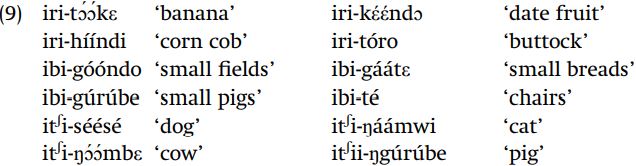

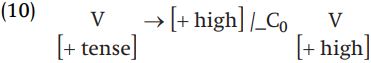

Another type of vowel harmony is vowel-height harmony. Such harmony exists in Kuria, where the tense mid vowels e, o become i, u before a high vowel. Consider (8), illustrating variations in noun prefixes (omo ~ umu; eme ~ imi; eke ~ ege ~ iki ~ igi; ogo ~ ugu) conditioned by the vowel to the right:

These examples show that tense mid vowels appear before the low vowel a and the tense and lax mid vowels e, ε, o, ɔ, which are [-high], and high vowels appear before high vowels, so based just on the phonetic environment where each variant appears, we cannot decide what the underlying value of the prefix is, [-high] or [+high]. Additional data show that the prefixes must underlyingly contain mid vowels; there are also prefixes which contain invariantly [+high] vowels.

Thus the alternations in (8) can be described with the rule (10).

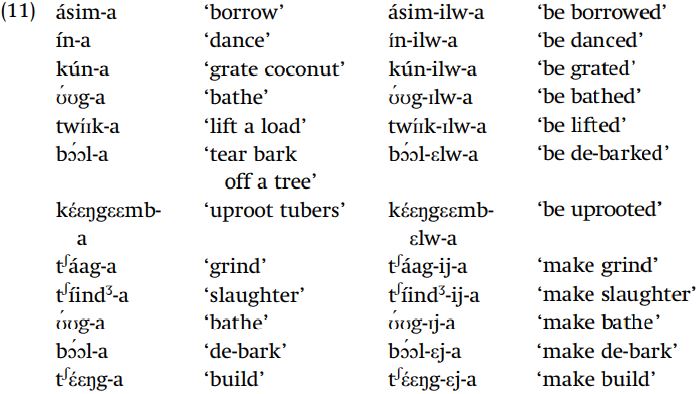

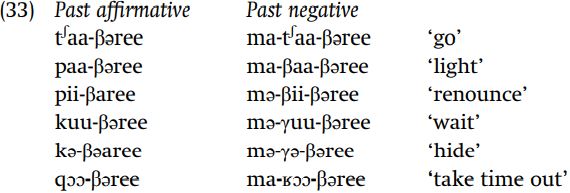

Another variety of vowel-height harmony is complete height harmony, an example of which is found in Matuumbi. This language distinguishes four phonological vowel heights, exemplified by the vowels a, ε, ɪ and i. The vowels of the passive suffix -ilw- and the causative suffix -ij- assimilate completely to the height of the preceding nonlow vowel [ε ɪ i].

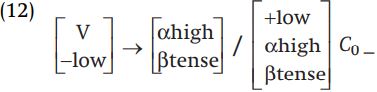

This process involves the complete assimilation of suffix vowels to the values of [high] and [tense] (or [ATR]) from the preceding nonlow vowel. Since the low vowel a does not trigger assimilation, the context after a reveals the underlying nature of harmonizing vowels, which we can see are high and tense. The following rule will account for the harmonic alternations in (11).

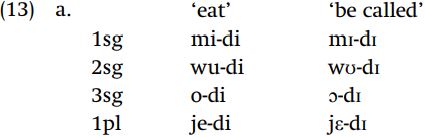

Akan exemplifies a type of vowel harmony which is common especially among the languages of Africa, which is assimilation of the feature ATR. In Akan, vowels within the word all agree in their value for [ATR]. In (13a) the prefix vowels are [+ATR] before the [+ATR] vowel of the word for ‘eat’ and [-ATR] before the [-ATR] vowel of ‘be called’; (13b) shows this same harmony affecting other tense–aspect prefixes.

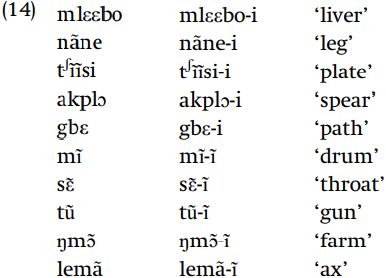

Vowel nasalization is also a common assimilatory process affecting vowels, and can be seen in the data of (14) from Gã. These data illustrate nasalization affecting the plural suffix, which is underlyingly /i/ and assimilates nasality from the immediately preceding vowel.

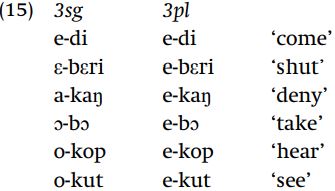

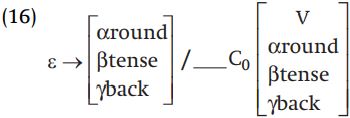

Another kind of vowel harmony, one affecting multiple features, is sometimes termed “place harmony,” an example of which comes from Efik. In Efik, the prefix vowel /ε/ (but not /e/) becomes [a] before [a], [ɔ] before [ɔ], [ε] before [ε], [e] before [e] and [i], and [o] before [o] and [u].

This process involves assimilation of all features from the following vowel, except the feature [high].

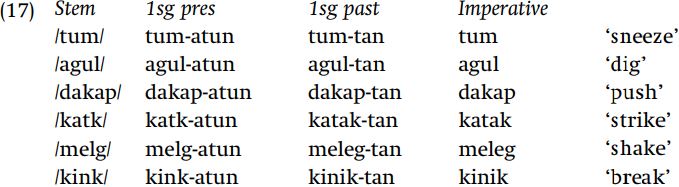

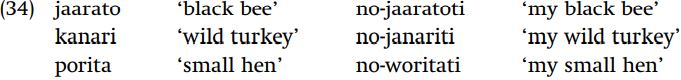

Finally complete vowel harmony, where one vowel takes on all features from a neighboring vowel, is found in some languages such as Kolami. This language has a rule of vowel epenthesis which breaks up final consonant clusters and medial clusters of more than two consonants. The inserted vowel harmonizes with the preceding vowel.

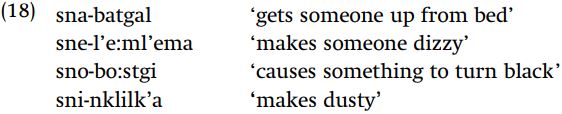

Another example of complete vowel harmony is seen in the following examples of the causative prefix of Klamath, whose vowel completely assimilates to the following vowel.

Complete harmony is unlikely to ever be completely general - all of these examples are restricted in application to specific contexts, such as epenthetic vowels as in Kolami, or vowels of specific affixal morphemes as in Klamath. Another context where total harmony is common is between vowels separated only by laryngeal glides h and ʔ, a phenomenon referred to as translaryngeal harmony, as illustrated in Nenets by the alternation in the locative forms to-hona ‘lake,’ pi-hina ‘street,’ pj a-hana ‘tree,’ pe-hena ‘stone,’ tu-huna ‘fire.’ The consequences of a completely unrestricted vowel harmony would be rather drastic - any word could only have one kind of vowel in it, were such a rule to be totally general.

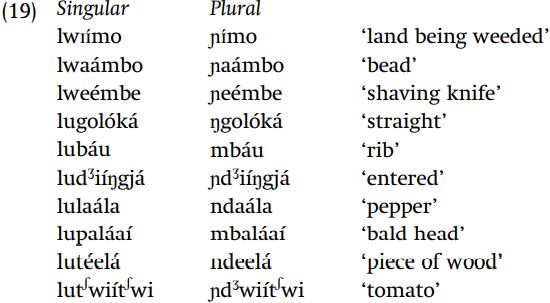

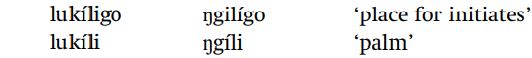

Consonant assimilations. One of the most common processes affecting consonants is the assimilation of a nasal to the place of articulation of the following consonant. An example of this process comes from Matuumbi, seen in (19), where the plural prefix /ɲ/ takes on the place of assimilation of the following consonant.

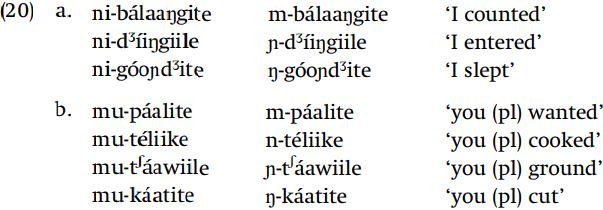

Place assimilation of nasals in Matuumbi affects all nasals, so the data in (20a) illustrate assimilation of preconsonantal /n/ resulting from an optional vowel deletion rule, and (20b) illustrates assimilation of /m/

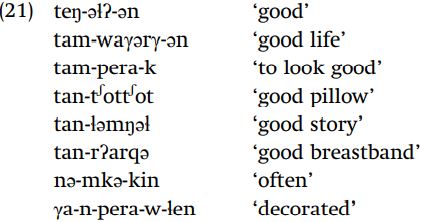

Sometimes, a language with place assimilation of nasals will restrict the process to a specific place of articulation. For instance, Chukchi assimilates ŋ to a following consonant, but does not assimilate n or m. Thus the stem teŋ ‘good’ retains underlying ŋ before a vowel, and otherwise assimilates to the following consonant: however, as the last two examples show, n and m do not assimilate to a following consonant.

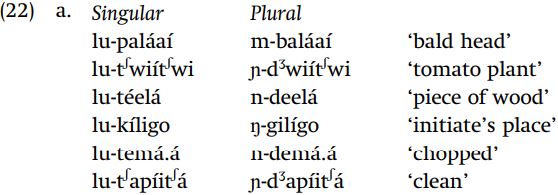

A common assimilation affecting consonants after nasals is postvocalic voicing, illustrated by Matuumbi in (22). The data in (22a) illustrate voicing of an underlyingly voiceless consonant at the beginning of a stem after the prefix ɲ. The data in (22b) show voicing of a consonant in a verb after the reduced form of the subject prefix ni. In these examples, the vowel /i/ in the prefix optionally deletes, and when it does, it voices an initial stop.

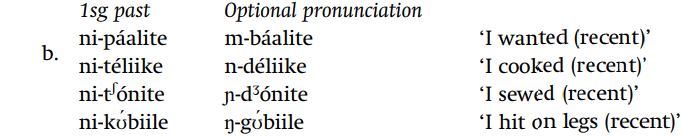

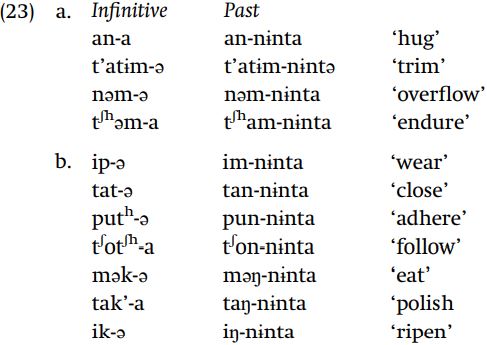

Stop consonants frequently nasalize before nasal consonants, and an example of this process is found in Korean. The examples in (23a) are stems with final nasal consonants; those in (23b) have oral consonants, revealed before the infinitive suffix a ~ ə, and undergo nasalization of that consonant before the past-tense suffix -nɨnta.

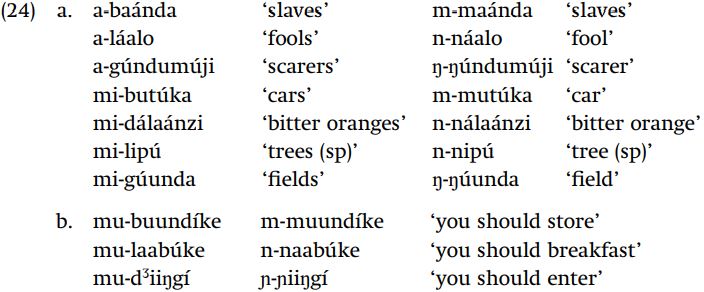

Matuumbi presents the mirror-image process, of postnasal nasalization (this process is only triggered by nasals which are moraic in the intermediate representation). On the left in (24a), the underlying consonant is revealed when a vowel-final noun-class prefix stands before the stem, and on the right a nasal prefix stands before the stem, causing the initial consonant to become nasalized. In (24b), nasalization applies to the example in the second column, which undergoes an optional rule deleting the vowel u from the prefix /mu/.

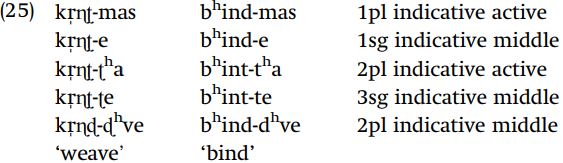

Many languages have a process of voicing assimilation, especially in clusters of obstruents which must agree in voicing. Most often, obstruents assimilate regressively to the last obstruent in the cluster. For example, in Sanskrit a stem-final consonant reveals its underlying voicing when the following affix begins with a sonorant, but assimilates in voicing to a following obstruent.

Other languages with regressive voicing assimilation are Hungarian and Russian.

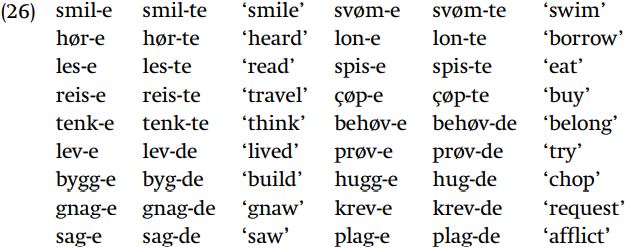

Progressive voicing harmony is also possible, though less common than regressive voicing. One example of progressive assimilation is found in Norwegian. The (regular) past-tense suffix is -te, and it shows up as such when attached to a stem ending in a sonorant or voiceless consonant, but after a voiced obstruent the suffix appears as -de.

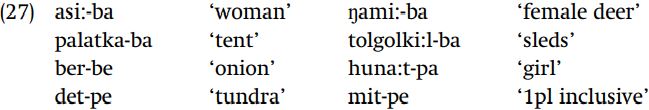

Another example of progressive voicing harmony is found in Evenki, where an underlyingly voiced suffix-initial consonant becomes devoiced after a voiceless obstruent: this is illustated below with the accusative case suffix /ba/.

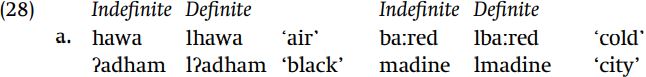

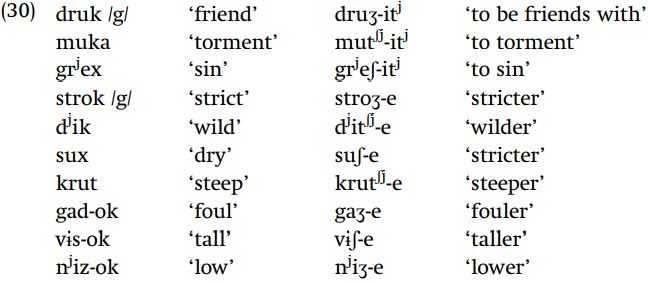

Complete assimilation of a consonant to a following consonant is found in Arabic. In the data of (28) from the Syrian dialect, the consonant /l/ of the definite article assimilates completely to a following coronal consonant. Examples in (a) show nonassimilation when the following consonant is non-coronal, and those in (b) provide stems that begin with coronal consonants

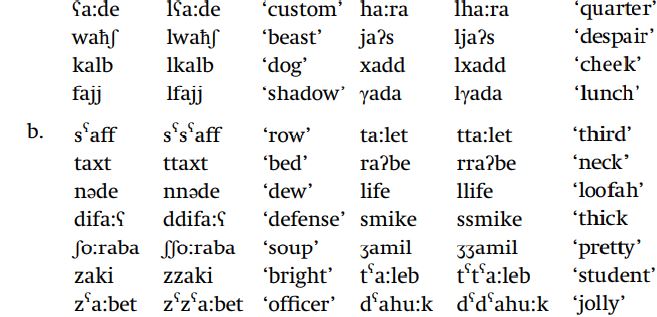

Consonants are also often susceptible to assimilation of features from a neighboring vowel, especially place features of a following vowel. One process is palatalization, found in Russian. A consonant followed by a front vowel takes on a palatal secondary articulation from the vowel, as the following data show.

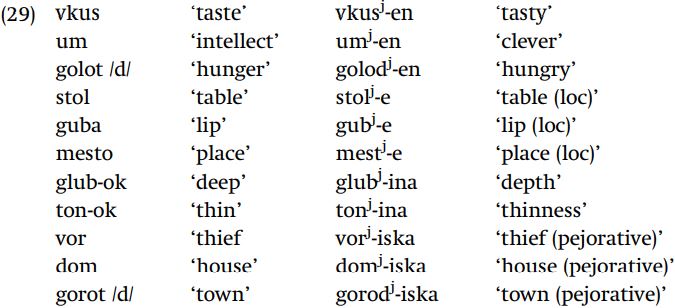

A second kind of palatalization is found in many languages, where typically velar but in some languages also alveolar consonants become alveopalatals: to avoid confusion with the preceding type of palatalization as secondary articulation, this latter process is often referred to as coronalization. This process is found in Russian: it is triggered by some derivational suffixes with front vowels, but not all suffixes.

Another common vowel-to-consonant effect is affrication of coronal obstruents before high vowels. An example of this is found in Japanese, where /t/ becomes [ts ] before [u] and [t ʃ ] before [i].

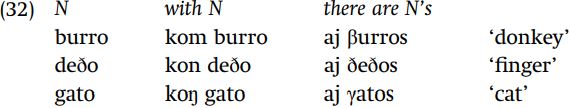

Outside the domain of assimilations in place of articulation, the most common segmental interaction between consonants and vowels (or, sometimes, other sonorants) is lenition or weakening. Typical examples of lenition involve either the voicing of voiceless stops, or the voicing and spirantization of stops: the conditioning context is a preceding vowel, sometimes a preceding and following vowel. An example of the spirantization type of lenition is found in Spanish, where the voiced stops /b, d, g/ become voiced spirants [β, ð, γ] after vocoids.

This can be seen as assimilation of the value [continuant] from a preceding vocoid.

An example of combined voicing and spirantization is found in Tibetan, where voiceless noncoronal stops become voiced spirants between vowels.

In some cases, the result of lenition is a glide, so in Axininca Campa, steminitial /k, p/ become [j, w] after a vowel.

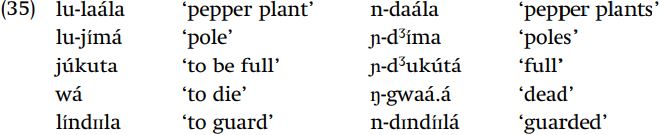

The converse process, whereby spirants, sonorants, or glides become obstruent stops after consonants, is also found in a number of languages – this process is generally referred to as hardening. In Matuumbi, sonorants become voiced stops after a nasal. The data in (35) illustrate this phenomenon with the alternation in stem-initial consonant found between the singular and plural.

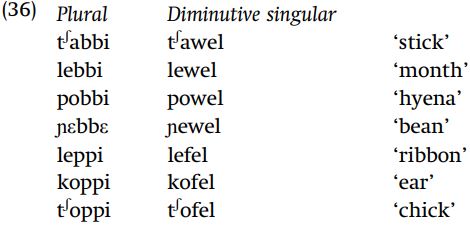

Another context where hardening is common is when the consonant is geminate. One example is found in Fula, where geminate spirants become stops. In (36), plural forms have a medial geminate (this derives by an assimilation to a following ɗ, so that [t ʃ abbi] derives from /tʃ aw- ɗ i/ via the intermediate stage tʃ awwi).

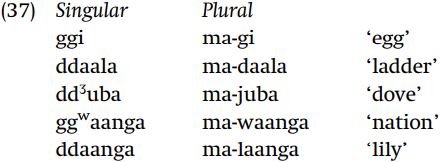

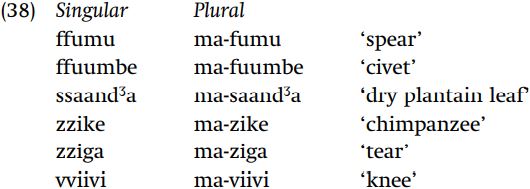

Geminate hardening also occurs in Ganda. In the data of (37), the singular form of nouns in this particular class is formed by geminating the initial consonant: the underlying consonant is revealed in the plural.

In this language, only sonorants harden to stops.

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)