Syllable weight

المؤلف:

April Mc Mahon

المؤلف:

April Mc Mahon

المصدر:

An introduction of English phonology

المصدر:

An introduction of English phonology

الجزء والصفحة:

113-9

الجزء والصفحة:

113-9

21-3-2022

21-3-2022

2045

2045

Syllable weight

There is one further aspect of syllable structure which provides evidence for the syllable-internal structure set out above. Here again, as in the case of poetic rhyme, the nucleus and coda seem to work together, but the onset does not contribute at all.

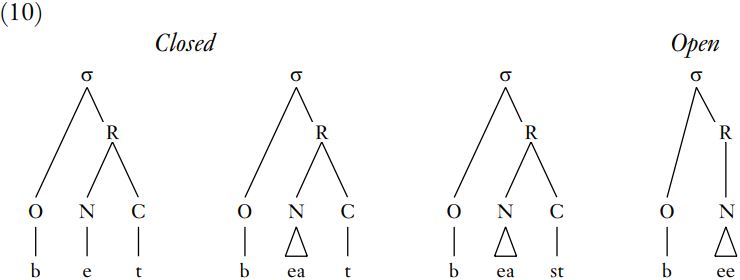

In fact, there are two further subdivisions of syllable type, and both depend on the structure of the rhyme. First, syllables may be closed or open: a closed syllable has a coda, while in an open syllable, the rhyme consists of a nucleus alone, as shown in (10). It does not matter, for these calculations, whether the nucleus and coda are simple, containing a single element, or branching, containing more than one: a branching nucleus would have a long vowel or diphthong, while a branching coda would contain a consonant cluster.

There is a second, related distinction between light and heavy syllables. A light syllable contains only a short vowel in the rhyme, with no coda, as in the first syllable of potato, report, about. Although the first two cases have onsets, and the third does not, all these initial syllables are still light, because onsets are entirely irrelevant to the calculation of syllable weight. If a syllable has a complex rhyme, then it is heavy; and complexity can be achieved in two different ways. First, a heavy syllable may have a short vowel, but one or more coda consonants, as in bet, best. Second, it may have a branching nucleus, consisting of a long vowel or diphthong; such a syllable will be heavy whether it also has a filled coda, as in beast, bite, or not, as in bee, by.

As we shall see in detail in the next chapter, syllable weight is a major factor in determining the position of stress in a word: essentially, no stressed syllable in English may be light. This means that no lexical word, or full word of English can consist only of a short vowel alone, with or without an onset, since such words, including nouns, verbs and adjectives, must be able to bear stress: thus, we have be, say, loss, but not *[bI], *[sε], *[lɒ]. On the other hand, function words like the indefinite article a, or the pronunciation [tə] for the preposition to, which are part of the grammatical structure of sentences and are characteristically unstressed, can be light. In cases where these do attract stress, they have special pronunciations [eI] and [tu:], where the vowel is long, the nucleus branches, and the syllable is therefore heavy.

There is one set of cases where a conflict arises between syllable weight on one hand, and the guidelines for the placement of syllable boundaries on the other: we have already encountered this in the discussion of bottle above. In most cases, these two aspects of syllable structure work together. For instance, potato, report, about each have a consonant which could form either the coda of the first syllable, or the onset of the second. Onset Maximalism would force the second analysis, placing the first [t] of potato, the [p] of report, and the [b] of about in onset position; this is supported by the evidence of aspiration in the first two cases. The first syllable of each word is therefore light; and since all three syllables are unstressed, this is unproblematic. Similarly, in words like penny, follow, camera, apple, Onset Maximalism would argue for the syllabifications pe.nny, fo.llow, ca.me.ra, and a.pple. However, in these cases the initial syllable is stressed, in direct contradiction of the pervasive English rule which states that no stressed syllable may be light. In these cases, rather than overruling Onset Maximalism completely, we can regard the problematic medial consonant as ambisyllabic, or belonging simultaneously in the coda of the first syllable and the onset of the second. It therefore contributes to the weight of the initial, stressed syllable; but its phonetic realization will typically reflect the fact that it is also in the onset of the second syllable. Consequently, as we saw earlier, the /l/ in hilly, follow appears as clear, as befits an onset consonant, while /r/ in carry is realized as [ɹ], its usual value in onset position, rather than being unpronounced, its usual fate in codas.

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة