Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Systemic differences

المؤلف:

April Mc Mahon

المصدر:

An introduction of English phonology

الجزء والصفحة:

94-8

19-3-2022

2856

Systemic differences

The first and most obvious difference between accents is the systemic type, where a phoneme opposition is present in one variety, but absent in another. Consonantal examples in English are relatively rare. As we have already seen, some varieties of English, notably SSE, Scots and NZE, have a contrast between /w/ and , as evidenced by minimal pairs like Wales and whales, or witch and which. Similarly, SSE and Scots have the voiceless velar fricative /x/, which contrasts with /k/ for instance in loch versus lock, but which is absent from other accents. NZE speakers will therefore tend to have one more phoneme, and Scots and SSE speakers two more, than the norm for accents of English.

, as evidenced by minimal pairs like Wales and whales, or witch and which. Similarly, SSE and Scots have the voiceless velar fricative /x/, which contrasts with /k/ for instance in loch versus lock, but which is absent from other accents. NZE speakers will therefore tend to have one more phoneme, and Scots and SSE speakers two more, than the norm for accents of English.

Conversely, some accents have fewer consonant phonemes than most accents of English. For instance, in Cockney and various other inner-city English accents, [h]-dropping is so common, and so unrestricted in terms of formality of speech, that we might regard /h/ as having disappeared from the system altogether. This is also true for some varieties of Jamaican English. In many parts of the West Indies, notably the Bahamas and Bermuda, there is no contrast between /v/ and /w/, with either [w] or a voiced bilabial fricative [β] being used for both, meaning that /v/ is absent from the phonemic and phonetic systems. The same contrast is typically missing in Indian English, but the opposition is resolved in a rather different direction, with the labio-dental approximant very frequently being used for the initial sound of wine and vine, or west and vest. Again, there is only a single phoneme in this case in Indian English.

very frequently being used for the initial sound of wine and vine, or west and vest. Again, there is only a single phoneme in this case in Indian English.

The number of accent differences involving vowels, and the extent of variation in that domain, is very significantly greater than in the case of consonants for systemic, realizational and distributional differences. This probably reflects the fact that the vowel systems of all English varieties are relatively large, so that a considerable number of vowels occupy a rather restricted articulatory and perceptual space; in consequence, whenever and wherever one vowel changes, it is highly likely to start to encroach on the territory of some adjacent vowel. It follows that a development beginning as a fairly minor change in the pronunciation of a single vowel will readily have a knock-on effect on other vowels in the system, so that accent differences in this area rapidly snowball. In addition, the phonetics of vowels is a very fluid area, with each dimension of vowel classification forming a continuum, so that small shifts in pronunciation are extremely common, and variation between accents, especially when speakers of those accents are not in day-to-day communication with each other, develops easily.

Systemic differences in the case of vowel phonemes can be read easily from lists of Standard Lexical Sets and the systems plotted from these on vowel quadrilaterals. If for the moment we stick to the four reference accents introduced in the last chapter, namely SSBE, GA, SSE and NZE, we can see that SSBE has the largest number of oppositions, with the others each lacking a certain number of these.

Comparing GA to SSBE, we find that GA lacks /ɒ/, so that LOT words are produced with /ɑ:/, as are PALM words, while CLOTH has the /ɔ:/ of THOUGHT. In this respect, SSBE is ‘old-fashioned’: it maintains the ancestral state shared by the two accents. However, in GA realizations of the earlier /ɒ/ have changed their quality and merged, or become identical with the realizations of either /ɑ:/ or /ɔ:/. GA also lacks the centring diphthongs of SSBE, so that NEAR, SQUARE, CURE share the vowels of FLEECE,FACE, GOOSE respectively, but since GA is rhotic, the former lexical sets also have a realization of /r/, while the latter do not. In this case, however, the historical innovation has been in SSBE. At the time of the initial settlement of British immigrants in North America, most varieties of English were rhotic, as GA still is; but the ancestor of SSBE has subsequently become non-rhotic. The loss of /r/ before a consonant or a pause in SSBE has had various repercussions on the vowel system, most notably the development of the centring diphthongs.

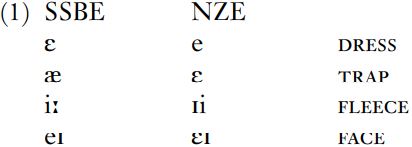

In systemic terms, NZE lacks only one of the oppositions found in SSBE, namely that between /I/ and /ə/; in NZE, both KIT and LETTER words have schwa. There are more differences in symbols between the SSBE and NZE lexical set lists ; but these typically reflect realisational, and sometimes distributional, rather than systemic differences, as we shall see in the next two sections. That is to say, I have chosen to represent the vowel of NZE TRAP as /ε/ and DRESS as /e/, FLEECE as /Ii/ and FACE as /εI/, to highlight the typical realisational differences between the two accents. However, in phonemic terms, the TRAP and DRESS vowel, and the FLEECE and FACE vowel, still contrast in NZE just as they do in SSBE. That is, the pairs of vowel phonemes in (1) are equivalent: they are symbolised differently because they are very generally pronounced differently (and we could equally well have chosen the same phonemic symbols in each case, to emphasise this parity, at the cost of a slightly more abstract system for NZE; see the discussion in Section 7.2.2 above), but the members of the pairs are doing the same job in the different accents.

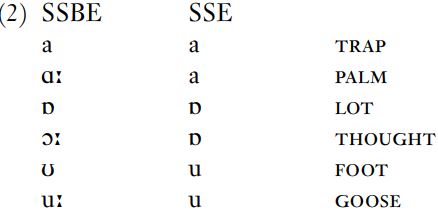

When we turn to SSE, however, we find a considerably reduced system relative to SSBE. As we might expect, given that SSE is rhotic, it lacks the centring diphthongs, so that NEAR, SQUARE, CURE share the vowels of FLEECE, FACE, GOOSE, though the former will have a final [ɹ] following the vowel. SSE also typically lacks the /ε:/ vowel of NURSE, with appearing here instead; so the NURSE and STRUT sets share the same vowel. Leaving aside vowels before /r/, however, there are three main oppositions in SSBE which are not part of the SSE system, as shown in (2)

appearing here instead; so the NURSE and STRUT sets share the same vowel. Leaving aside vowels before /r/, however, there are three main oppositions in SSBE which are not part of the SSE system, as shown in (2)

Each of these three contrasting pairs of vowel phonemes in SSBE corresponds to a single phoneme in SSE. While Sam – psalm, cot – caught, and pull – pool are minimal pairs in SSBE, establishing the oppositions between /a/ and /ɑ:/, /ɒ/ and /ɔ:/, and /υ/ and /u:/ respectively, for SSE speakers the members of each pair will be homophonous. There is no vowel quality difference; and the Scottish Vowel Length Rule, which makes vowel length predictable for SSE and Scots, means there is no contrastive vowel quantity either. There is some variation in SSE in this respect: speakers who have more contact with SSBE, or who identify in some way with English English, may have some or all of these oppositions in their speech. If an SSE speaker has only one of these contrasts, it is highly likely to be /a/ – /ɑ/; if /υ/ and /u/ are contrasted, we can predict that the /ɒ/ – /ɔ/ and /a/ – /ɑ/ pairs also form part of the system.

Of course, such systemic differences are not restricted to the reference accents surveyed above. For instance, within British English, many accents of the north of England and north Midlands fail to contrast /υ/ and , so that put and putt, or book and buck all have /υ/. In some parts of the western United States, speakers typically lack the /ɑ:/ – /ɔ:/ opposition found in GA, and will therefore have /ɑ:/ in both cot and caught. Other varieties of English have an even more extreme reduction of the vowel system relative to SSBE. These are typically accents which began life as second language varieties of English: that is, they were at least initially learned by native speakers of languages other than English, although they may subsequently have become official language varieties in particular territories, and be spoken natively by more recent generations. Inevitably, these varieties have been influenced by the native languages of their speakers, showing that language contact can also be a powerful motivating force in accent variation.

, so that put and putt, or book and buck all have /υ/. In some parts of the western United States, speakers typically lack the /ɑ:/ – /ɔ:/ opposition found in GA, and will therefore have /ɑ:/ in both cot and caught. Other varieties of English have an even more extreme reduction of the vowel system relative to SSBE. These are typically accents which began life as second language varieties of English: that is, they were at least initially learned by native speakers of languages other than English, although they may subsequently have become official language varieties in particular territories, and be spoken natively by more recent generations. Inevitably, these varieties have been influenced by the native languages of their speakers, showing that language contact can also be a powerful motivating force in accent variation.

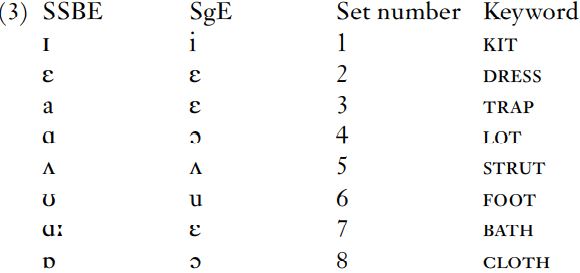

One case involves Singapore English. Singapore became a British colony in 1819, and English was introduced to a population of native speakers of Chinese, Malay, Tamil and a number of other languages. Increasingly today, children attend English-medium schools, and use English at home, so that Singapore English is becoming established as a native variety. Its structure, however, shows significant influence from other languages, notably Malay and Hokkien, the Chinese ‘dialect’ with the largest number of speakers in Singapore. As with many accents, there is a continuum of variation in Singapore English, so that non-native speakers are likely to have pronunciations more distant from, say, SSBE: thus, while a native Singapore English speaker will say [maIl] ‘mile’, a second-language speaker who is much more influenced by his native language may say . Increasingly, younger speakers of Singapore English are also looking to American rather than British English as a reference variety, so that further change in the system is likely. The system presented as Singapore English (SgE) in (3) is characteristic of native or near-native speakers. Note that SgE has no contrastive differences of vowel length, and that /ɯ/ is the IPA symbol for a high back unrounded vowel.

. Increasingly, younger speakers of Singapore English are also looking to American rather than British English as a reference variety, so that further change in the system is likely. The system presented as Singapore English (SgE) in (3) is characteristic of native or near-native speakers. Note that SgE has no contrastive differences of vowel length, and that /ɯ/ is the IPA symbol for a high back unrounded vowel.

As (3) shows, many of the vowel oppositions found in SSBE are absent from SgE; and in the great majority of cases, the main reason for the changes in SgE is the structure of other languages spoken in Singapore. (The same contact influences account for realisational differences between SgE and other Englishes, which we consider in the next section.) Looking at the various phoneme mergers in SgE in more detail, we find the patterns in (4).

In all these cases, lexical sets which have distinct vowels in SSBE (and often in other accents too) share a single vowel in SgE; and furthermore, this vowel tends to correspond to the vowel found in either Hokkien, or Malay, or both. Thus, instead of /ε/ versus /a/, SgE has only /ε/; both Hokkien and Malay have only a higher vowel in this area, namely /e/ (and realizationally, SgE /ε/ raises to [e] before plosives and affricates, as in head, neck, neutralizing the opposition between /e/, the monophthong found in FACE words, and /ε/ in TRAP, DRESS in this context, so that bread – braid, red – raid, bed – bade are homophones). The merger of the KIT,FLEECE sets follows the pattern for Malay and Hokkien, and the same is true of STRUT/PALM/START; neither Malay nor Hokkien has any low back vowels, and the SgE vowel for all these sets is higher and more central; in SgE this merger means that cart and cut, or charm and chum, are homophonous.

In the cases of LOT/THOUGHT, and FOOT/GOOSE, SgE follows the Hokkien pattern; Malay has neither /ɒ/ nor /ɔ/, but both /υ/ and /u/. Whichever local language has exerted most influence in any particular instance, it is clear that native language systems have acted as a filter or template for non-native learners of Singapore English, creating the vowel system found today.

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)