Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Vowel features and allophonic rules

المؤلف:

April Mc Mahon

المصدر:

An introduction of English phonology

الجزء والصفحة:

85-7

19-3-2022

1971

Vowel features and allophonic rules

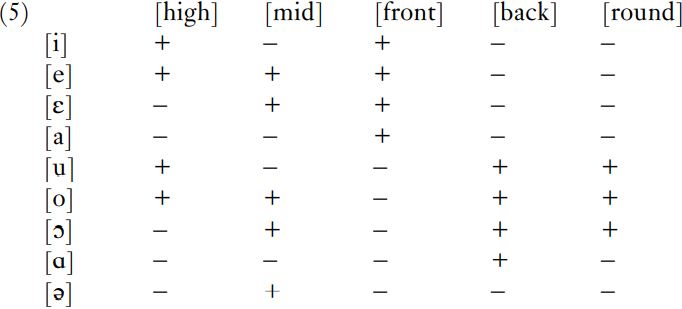

Once phonemic contrasts have been established for the accent in question, and the appropriate representation for each phoneme has been selected, the realizations of those phonemes must be determined and rules written to describe allophonic variation. Again, features and rule notation can be used to formalize these statements. We saw that vowels are [+syllabic, –consonantal, +sonorant, +voice, –nasal]. To distinguish English vowels appropriately, we also require the features [±high], [±mid] for the dimension of tongue height; [±front], [±back] for place of articulation; and [±round]. These give the illustrative matrix in (5).

These features can distinguish four contrastive degrees of vowel height, and three degrees of frontness, which allows all varieties of English to be described. However, /i:/ and /I/, and /u:/ and /υ/, will be identical in this matrix. In SSBE and GA, the former in each pair is typically long, and the latter short; and long vowels are also articulated more extremely, or more peripherally than corresponding short ones: the long high front vowel is higher and fronter than the short high front vowel, while the long high back vowel is higher and backer than its short counterpart. The question is whether we regard this as primarily a quality or a quantity difference. If we take quality as primary, we can regard /i/, /u/, /ɑ/, /ɔ/ as [+tense], or more peripheral, and simply write a redundancy rule to say that all tense vowels are phonetically long. On the other hand, we could do the opposite, and take length as the important factor, so these vowels are long /i:/, /u:/, /ɑ:/ and /ɔ:/, and redundantly also more peripheral.

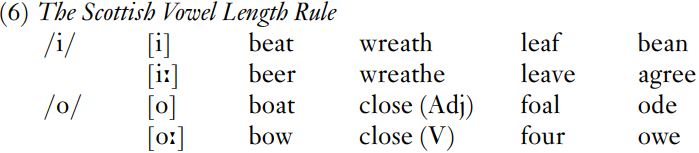

For most accents of English, we could choose either solution, although most phonologists would select either length or tenseness as relevant at the phoneme level, with the other simply following automatically, to minimize redundancy in the system. However, in SSE and Scots dialects, it matters which we choose. This is because vowels in Scottish accents (and some related Northern Irish accents) are unique among varieties of English in one respect: we can predict where vowels are phonetically long, and where they are phonetically short. Vowels become long before and at the end of a word, but they are short everywhere else, as shown in (6).

and at the end of a word, but they are short everywhere else, as shown in (6).

/I/, /ε/ and /A/, which are short and lax in other accents, do not lengthen in any circumstances. In SSE and Scots, then, we can define the two classes of phonemic vowels as lax (the three which never lengthen) and tense (the others, which are sometimes long and sometimes short, in predictably different environments). It is possible to predict length from [±tense], but not the other way around. The allophonic rule involved will then state that tense vowels lengthen before /r/, before a voiced fricative, or before a word boundary (that is, in word-final position), to account for the data in (6).

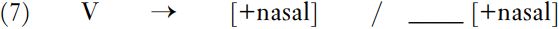

Other allophonic rules are more general. For instance, in all varieties of English, vowels become nasalized immediately before nasal consonants; the velum lowers in anticipation of the forthcoming nasal, and allows air to flow through the nasal as well as the oral cavity during the production of the vowel. If you produce cat and can, then regardless of whether your vowel is front or back, there will be a slight difference in quality due to nasalization in the second case; you may hear this as a slight lowering of the pitch. This rule is shown in (7); note that the symbol V here means ‘any vowel’.

Just as for consonants, then, some allophonic rules specifying the realizations of vowel phonemes are found very generally in English (and may in fact, as in the case of the nasalization process in (7), reflect universal phonetic tendencies); others, like the Scottish Vowel Length Rule, are peculiar to certain accents.

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)